Pictures of the Floating World

Amanda Shubert is the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

Uikyo-e is a form of woodblock printmaking that flourished between in Japan the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The word Uikyo-e means “pictures of the floating world.” Traditionally, these prints depict a world of sumptuous colors, elegant women, and dazzling theatrical illusions.

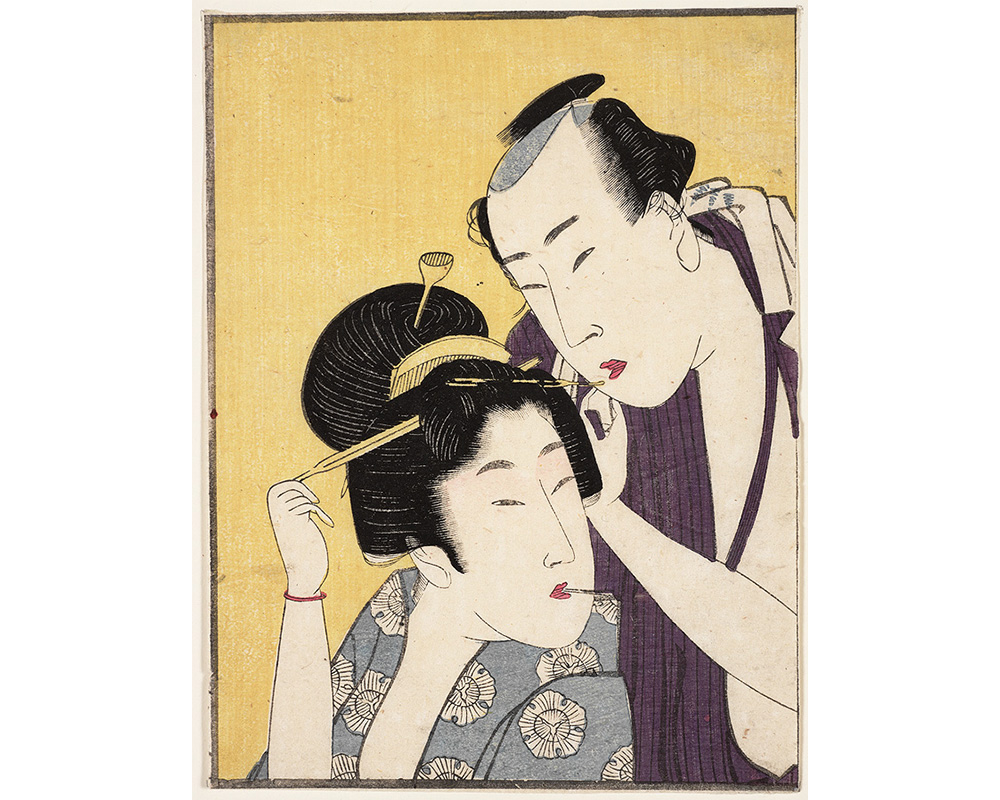

Toyukuni III (Utagawa Kunisada). Woman Standing in Bow of Boat, Winter, 1820s. Woodcut printed in color on paper. Gift of Helen D. La Monte, class of 1895. SC 1970.14.3.

The “floating world” of Ukiyo-e refers to the pleasure quarters of Edo. Edo, a modest fishing village, became the capital of Japan under the warlord government called the Tokugawa shogunate that held power from 1603 until 1868. The village was transformed into a vibrant metropolis known for its entertainment culture, featuring music, Kabuki and puppet theater, geishas, and woodblock prints.

Edo flourished. Within a little over a century of this new government rule, it became the largest city in the world. When the Meiji Restoration abolished the shogunate in 1868, Edo was renamed Tokyo, meaning “eastern capital.” Thus, Japanese printmaking and its tradition of beauty and elegance is tied up in the history and rise of the city we now know as Tokyo. Ukiyo-e is an art of ethereal and ephemeral beauty and pleasure, but it is also very much an urban tradition – both a product of this urban expansion and its visual record.

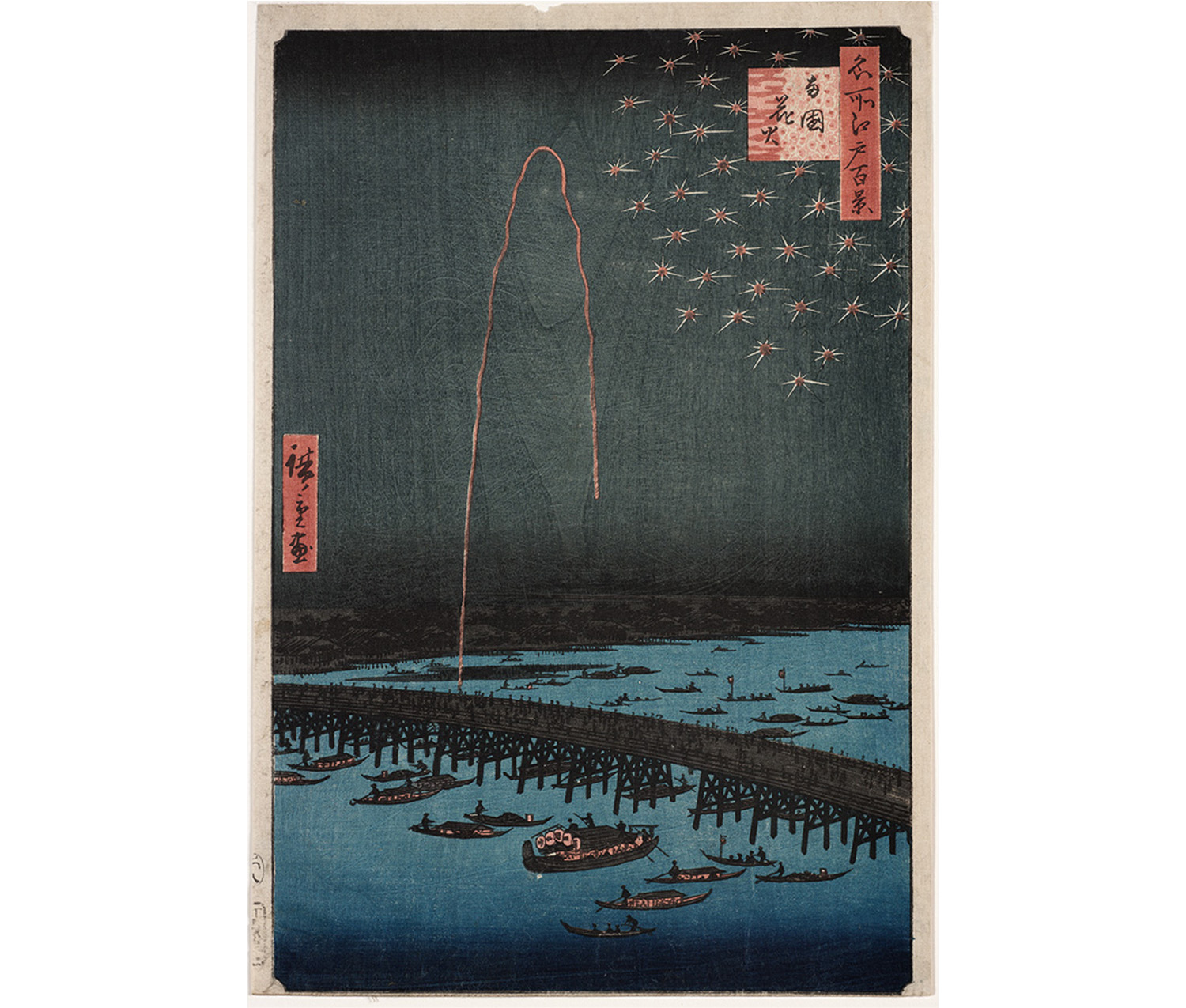

The Japanese print scholar Sandy Kita points out that Ukiyo-e presents a paradox in its name and its history. “Ukiyo” means “floating world,” and “-e” means “pictures, paintings or illustrations.” But the word ukiyo, as a common noun, precedes the pleasure quarters of Tokugawa Japan by seven or eight centuries, carrying a rather different definition: “the present” or “here and now.” Therefore, Ukiyo-e refers simultaneously to pictures of the floating world and pictures of the here and now, pictures of the illusory and pictures of the real. This print of fireworks over the water nicely encompasses this blend of the ephemerality of the here and now and the almost fantastical beauty of reality:

Utagawa Hiroshige. Japanese, 1797–1858. Fireworks at Ryōgoku Bridge, No. 98 from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1958 (8th month). Woodcut printed in color on paper. Purchased with the Winthrop Hillyer Fund. SC 1915.10.13.

This second translation of Ukiyo-e as “the here and now” might help explain the preponderance of landscape prints in the Ukiyo-e tradition, particularly those by nineteenth century artists Ando Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai. These artists are most famous for their series of Edo landscapes – for example, Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido and Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji – which exhibit a documentary style that seems far removed from the Floating World of fantasy and illusion.

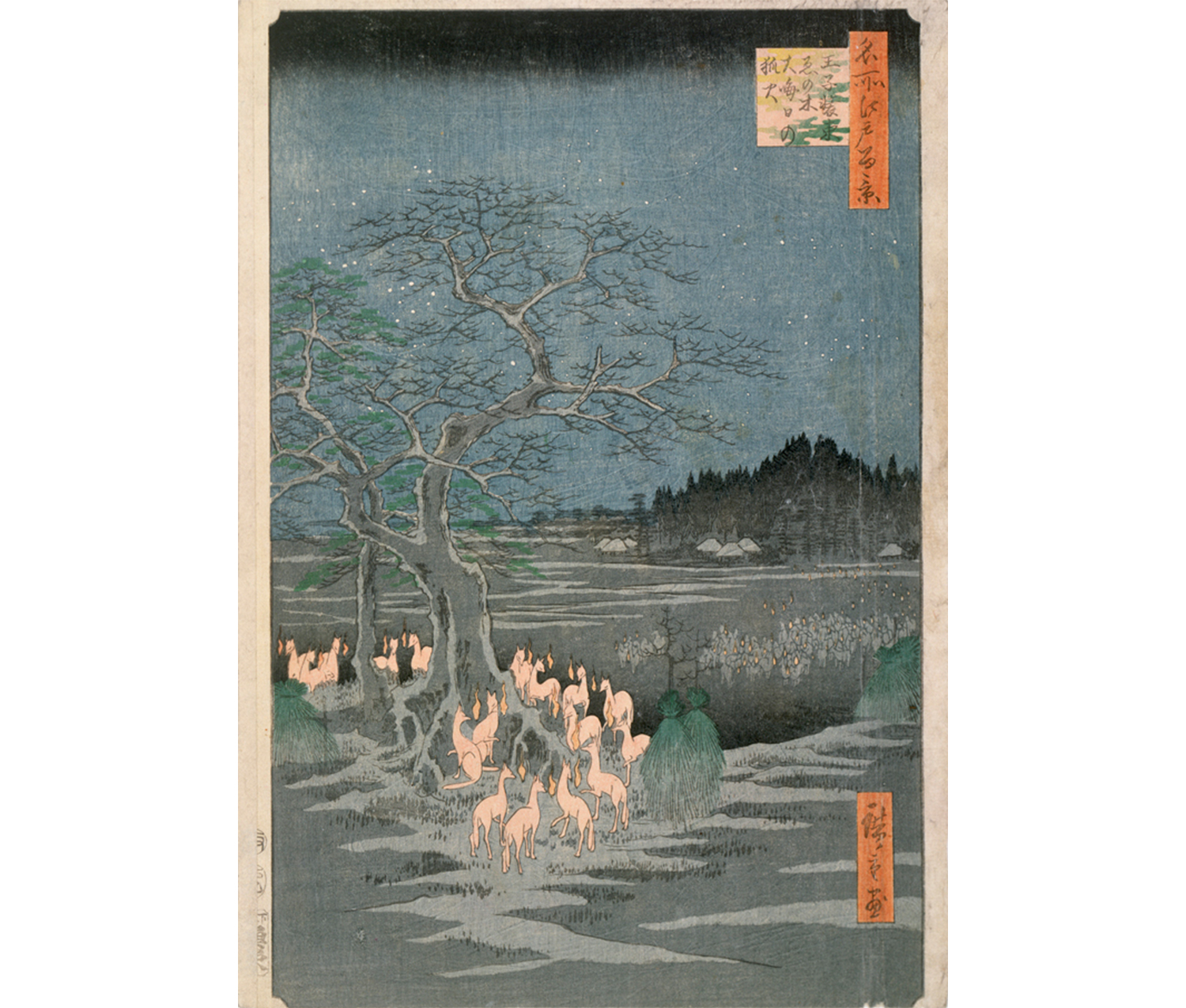

These landscape prints are more realism than fancy. Occasionally, however, they combine realism with legend or myth, as in this print of the New Year’s Eve Foxfires from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo:

Ando Hiroshige. Japanese, 1979–1859. New Year's Eve Foxfires at Nettle Tree, Oji, No. 118, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, late 1830s. Woodcut printed in color on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James Barker (Margaret Clark Rankin, class of 1908). SC 1968.383.

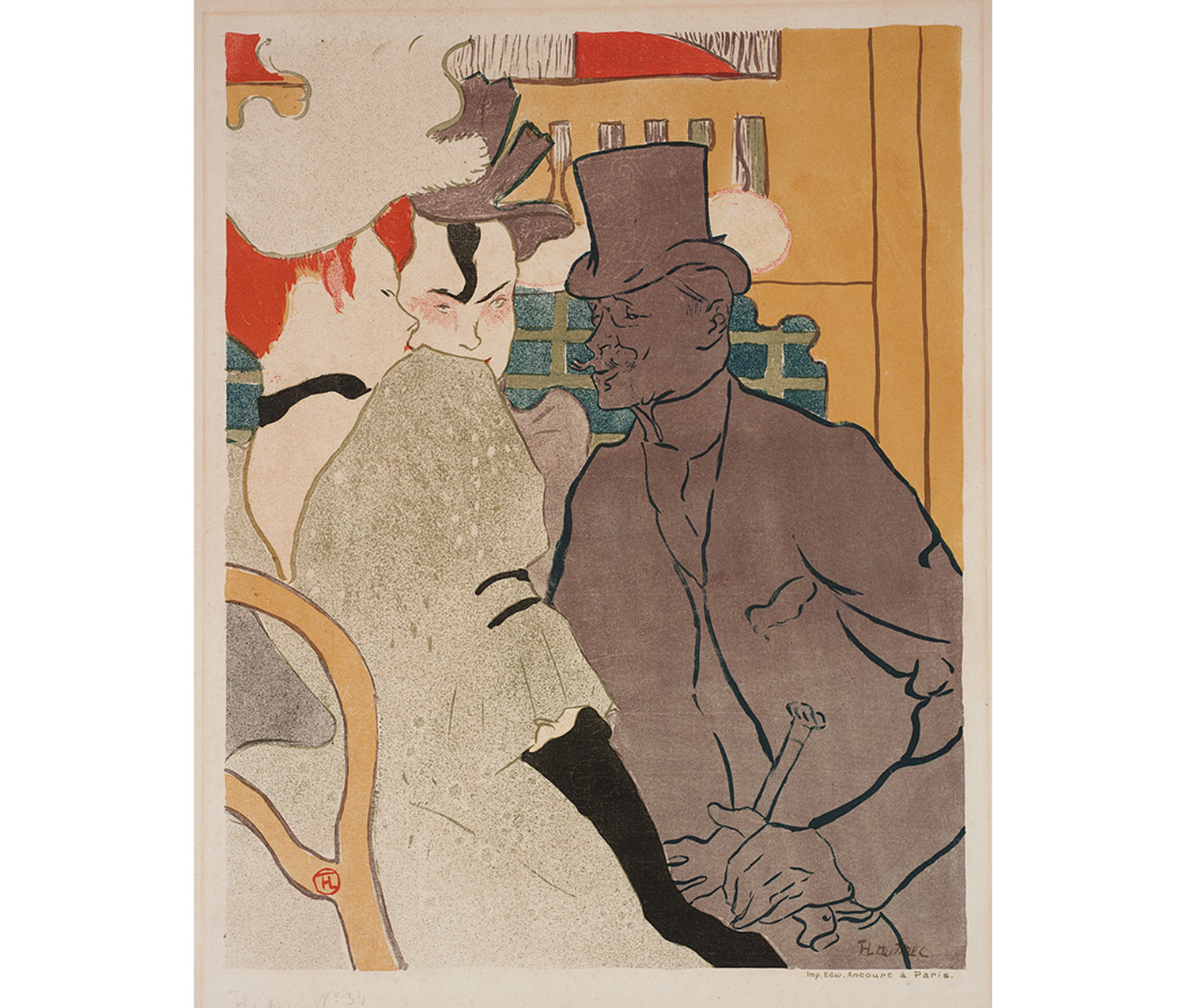

The centrality of Ukiyo-e in Japanese culture began to wane in the 1850s, when Japan opened up trade with the west and photography, a newly minted technology, gained currency in Japan. At the same time, artists like Pierre Bonnard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas were becoming fascinated by Japanese prints, incorporating the aesthetic and sensibility of ukiyo-e into their paintings and prints. It is easy to imagine how ukiyo-e, with its view of reality as ephemeral and subjective, appealed to these Impressionist artists.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. French, 1864–1901. L’anglais Warner au Moulin Rouge, ca. 1892. Brush and spatter lithograph in olive green, aubergine, blue, red-orange, yellow and black on originally buff, now brown, Van Gelder laid paper. Gift of Thomas A. Kelly. SC 1983.27.