Rembrandt's The Three Crosses

Amanda Shubert is the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

Drypoint prints are made by using an etching needle—a metal tool with a fine tip—to create incisions directly on a copper plate. When you etch the lines into the plate, the needle pulls up a fine burr of copper around the lines. Because of the burr, a drypoint line holds more ink than an etched or engraved line. It prints darkly and thickly, creating velvety black textures, deep shadows, and dramatic tonal variation.

Drypoint lines are more fragile than etching or engraving lines. They produce fewer impressions, because the burr wears down easily. This explains why Rembrandt’s marvelous drypoint print The Three Crosses exists in five states. The states are different versions of the same print; each state represents changes made to the copper plate because the burr had worn down and the plate needed to be touched up. Print lovers are obsessed with the little alterations you can find between different states of the same print. What distinguishes The Three Crosses is that the differences between the third and fourth states are dramatic. Rembrandt completely re-invents the print, not just compositionally, but tonally: the meaning changes.

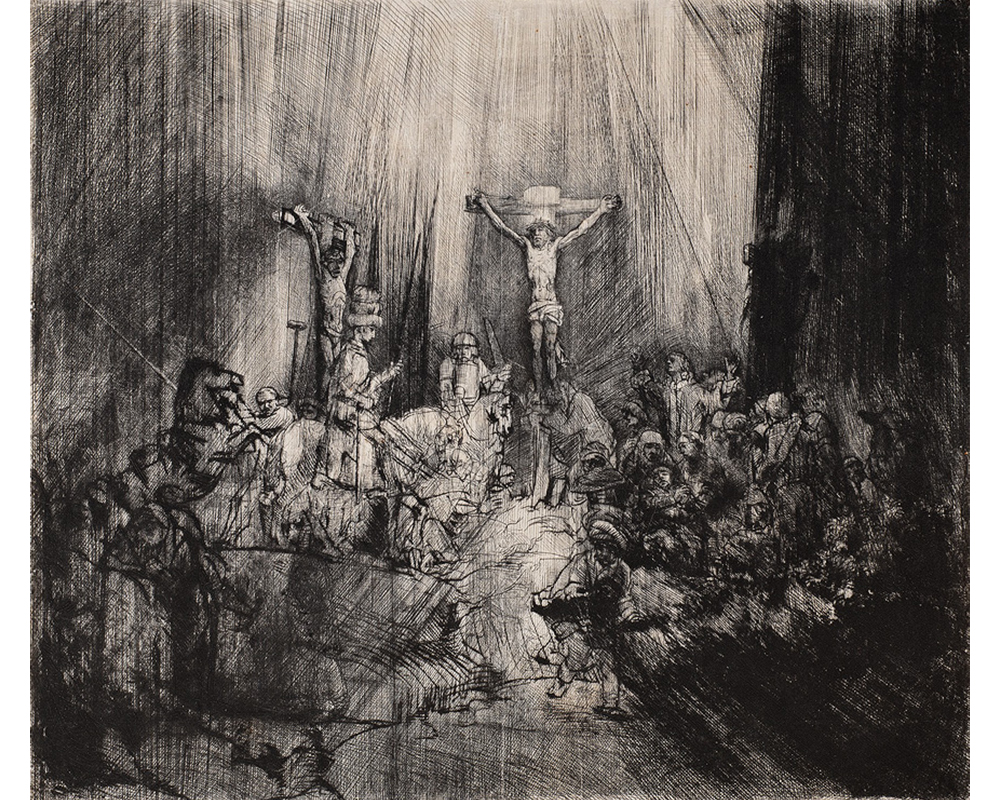

Take a look at our fourth state of The Three Crosses, shown above.

Now compare it to this image of the third state.

In the fourth state, Rembrandt introduces new figures—two mounted soldiers to the left of the cross—and re-draws the group at the right, including St. John and Mary. The figure of the centurion changes, too. In early states, he kneels before Christ; in late states he is mounted on a horse. The second thief on the cross is obscured because Rembrandt has etched over the right side of the plate, creating a deep ominous shadow over the scene. The velveteen depth and intensity of those black lines comes from the amazing use of drypoint.

The story the print depicts is the crucifixion of Christ alongside two thieves (in the print, Christ is in the center, with one thief on each side). The crucifixion is ultimately a tale of redemption: Christ’s sacrifice brings about the salvation of humankind. But the fourth state is so dark and bleak, it casts doubt upon the redemption narrative. The looming shadow that threatens to engulf the whole scene, the rearing horse, the obscurity of the figures, and the emphasis on Christ’s suffering transforms The Three Crosses from an image of pathos and sacrifice to one of darkness, doubt and chaos.