Remembering Jay Bolotin (1949-2024)

Aprile Gallant is Mary Walcott Keyes 1931 Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs and Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs.

Jay Bolotin was a handful. To his credit, I think he would be pleased to be described as such. He was also multi-talented, generous, a brilliant storyteller, and a lot of other things besides. Like his art, trying to describe Jay is an exercise in the complete limitations of language.

I was fortunate to have been able to work with him and call him friend: spending time with Jay was always engrossing, stimulating and a whole lot of fun.

Jay Bolotin installing his exhibition of drawings for The Jackleg Testament Part Two at the Carl Solway Gallery, Cincinnati, Ohio, 2010. Photograph by Anita Douthat

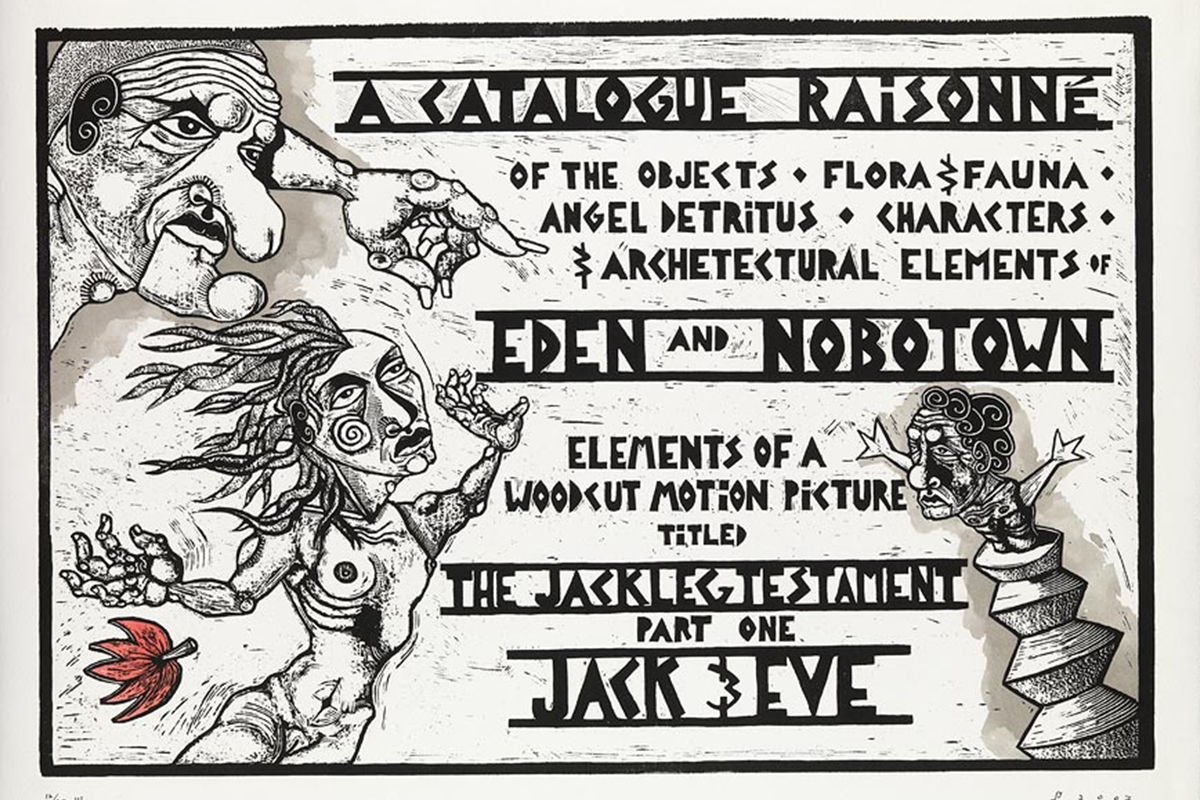

I first became aware of Jay while attending an art fair in New York (the sadly defunct EAB Editions Fair in 2010 to be exact). At a curator’s breakfast event, I saw hungry curators making a beeline through the central corridor of the fair headed for coffee and pastries. Suddenly, many of them stopped, turned, and stood slack-jawed staring to the right. Intrigued, I followed, and was amazed to see a movie playing on a screen in the booth for the Solway Gallery. This was my first glimpse of The Jackleg Testament, Part One: Jack & Eve, a 63-minute opera made of Jay’s woodcuts which he carved, printed, scanned, colorized and animated. He also wrote the story, the libretto and was one of the singers. It’s about as complex-fabulous-engrossing as it sounds.

Still from the film The Jackleg Testament, Part One: Jack & Eve, 2005

SCMA acquired a copy of the The Jackleg Testament, Part One: Jack & Eve including a portfolio of the woodcuts for the SCMA collection, and we decided to show them in a special exhibition in 2012. While contemplating engaging with the artist, I thought to myself: this guy is either a genius or completely unhinged. Fortunately for me, Jay was definitely the former.

Title page from the portfolio The Jackleg Testament, Part One: Jack & Eve, 2005. Woodcut

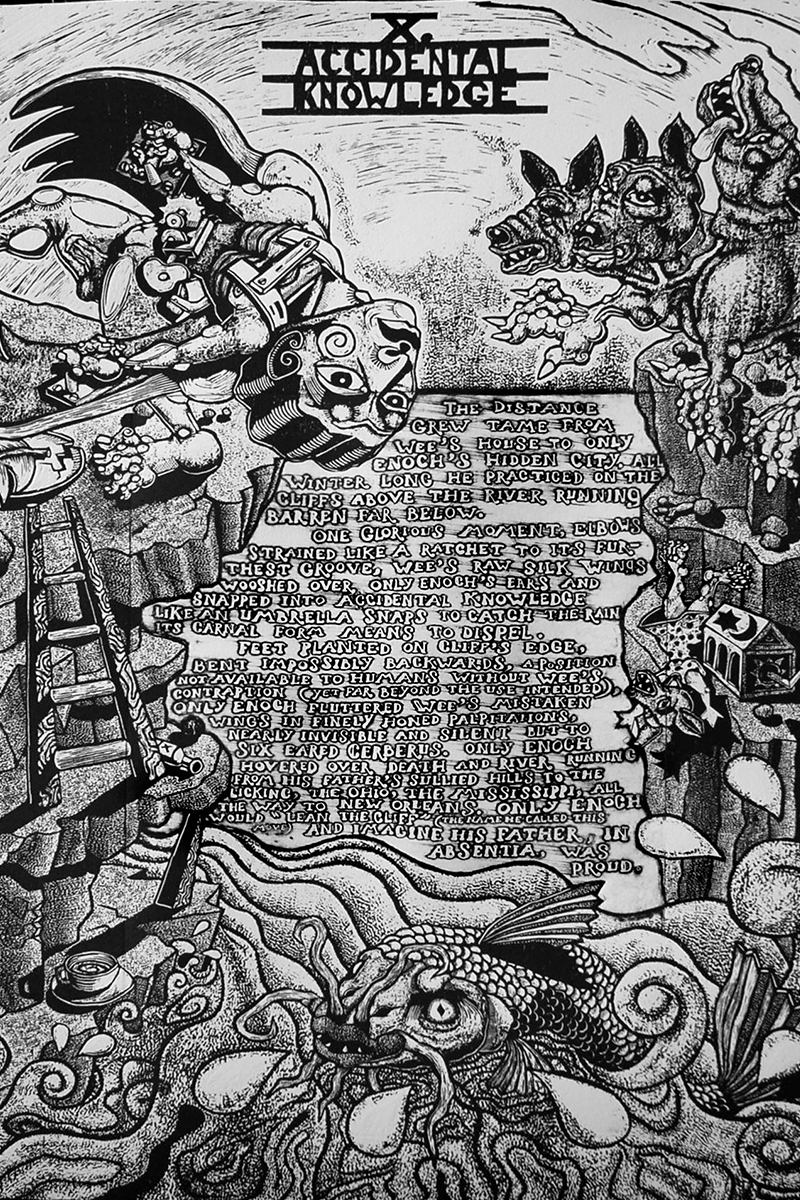

Making a movie out of woodcuts is certainly not the easy road, but after meeting Jay it all made sense. He was deeply engaged in process and allowing his vision the time and space to develop. It took him five years to make The Jackleg Testament, Part One as he worked on the woodcuts and movie simultaneously. He worked non-stop and was always experimenting with new ways of doing things. He built 3D models for his next movie, The Jackleg Testament, Part Two: The Book of Only Enoch, which also includes animated drawings among other things (you need to use the phrase “among other things” a lot when talking about Jay’s work—his approach to art was open and expansive). He taught himself film techniques and computer programs so that he could make his stories come alive. He created a series of relief etchings as he developed the narrative for The Book of Only Enoch. He met talented people and brought them into his world, developing deep and productive collaborations. He made sculpture, prints, music, opera sets—the vast range of his artistic pursuits was nothing short of amazing.

Accidental Knowledge, 2012. Print made during the development of The Jackleg Testament, Part Two: The Book of Only Enoch. Woodcut and relief etching

Jay’s work is somewhat confounding and filled with contradictions. A staunch magical realist with a herculean work ethic who produced literary-based projects of sprawling and epic proportions, he seemed to have been balancing on the verge of “emergence” for over 40 years. Working and showing steadily, Jay received sporadic intense public attention, not only in his adopted city of Cincinnati but nationally and internationally as well, only to drop off the radar once again, as he immersed himself in another project.

Jay kept me updated on the progress of his various collaborations in art and music: a CD of music he recorded in the 1970s when he was a singer-songwriter in Nashville; completion of The Silence of Professor Tösla, a collaborative film with Amherst professor Ilan Stavans; his stint as artist-in-residence and upcoming exhibition at the University of Kentucky (The Jackleg Testament, Part Two: The Book of Only Enoch will be on view at the University of Kentucky Art Museum from January 17–May 31, 2025), and many more. He stopped in Northampton for coffee every year on his way to or from somewhere. Although he was bursting with ideas and energy his speech was slow and soft with frequent pauses. If you weren’t paying attention, you might miss the sardonically funny thing he had just said.

Jay made me believe that magic was still possible (I can actually imagine his wry smile and cocked eyebrow upon hearing such a statement). He pursued a vision that might have looked to be out of step with contemporary culture, but he created a body of work that is complex, rich, varied, and endlessly satisfying to study. You can make an appointment to see some of Jay’s prints in the SCMA collection by contacting us at ccenter@smith.edu. It will always be an honor to share the work of this talented man. He still had so much to do. I will miss him terribly.