Robetta’s Adoration of the Magi

Guest blogger Julie Warchol was a participant in the 2011 Summer Institute in Art Museum Studies and is currently a curatorial volunteer in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

The Adoration of the Magi, a recently acquired engraving by Cristofano di Michele (1462–after 1534), simply known as Robetta, offers an intriguing and enlightening view of artistic influences and the painter-engraver relationship at the turn of the 16th-century. Robetta was born in Florence in 1462, the son of a hosier, or stocking maker. Like many men of his time, he worked in his father’s trade until 1498 when, at the age of 36, he decided to instead pursue a career as a goldsmith and artist. This kind of career change was quite unusual, as most Renaissance artists and craftsmen started apprenticing in their early teens for a lifelong career. While relatively little is known about his life, except for his public records and a brief mention in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, we do know that he produced only about three dozen engravings, including his masterpiece The Adoration of the Magi.

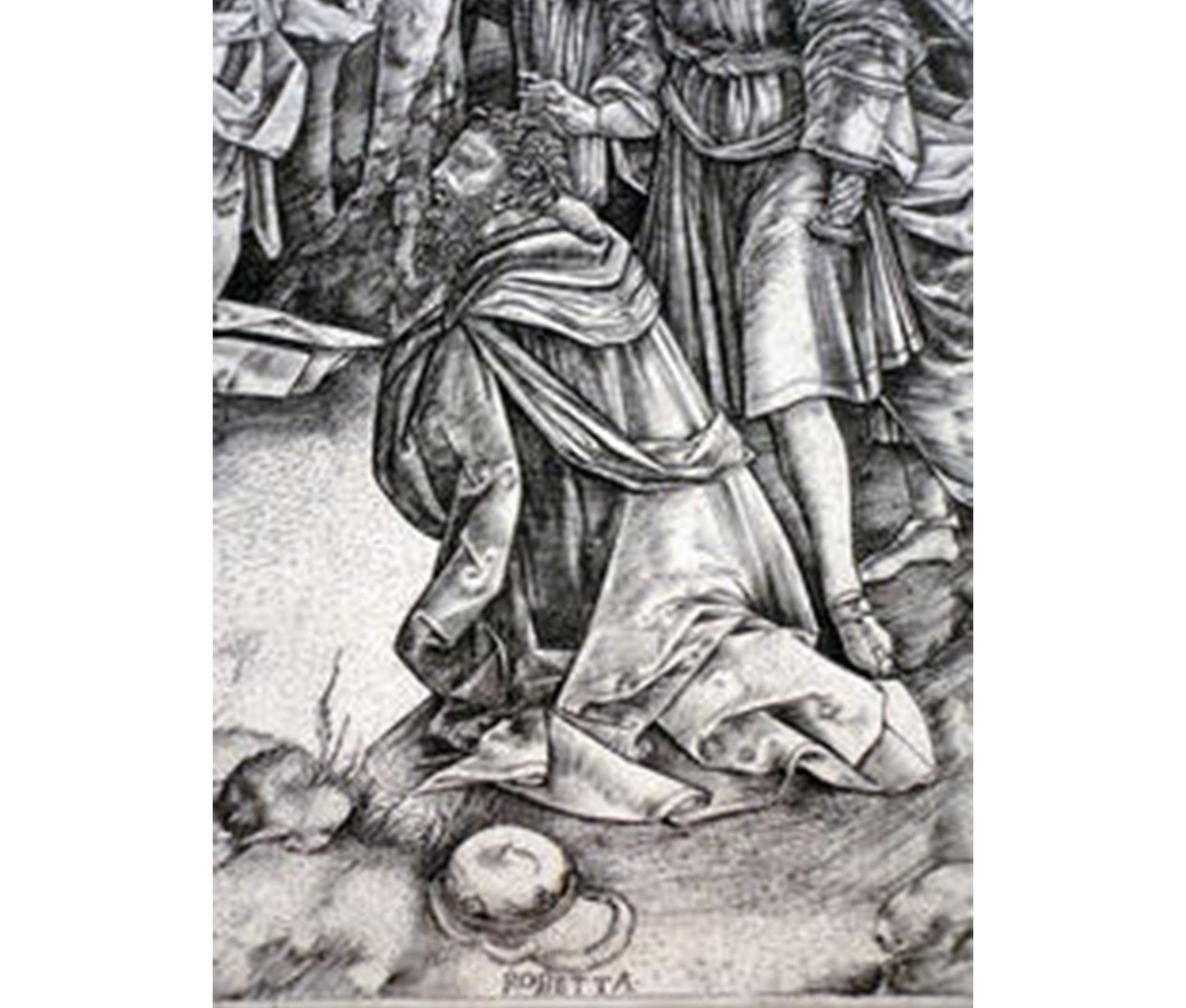

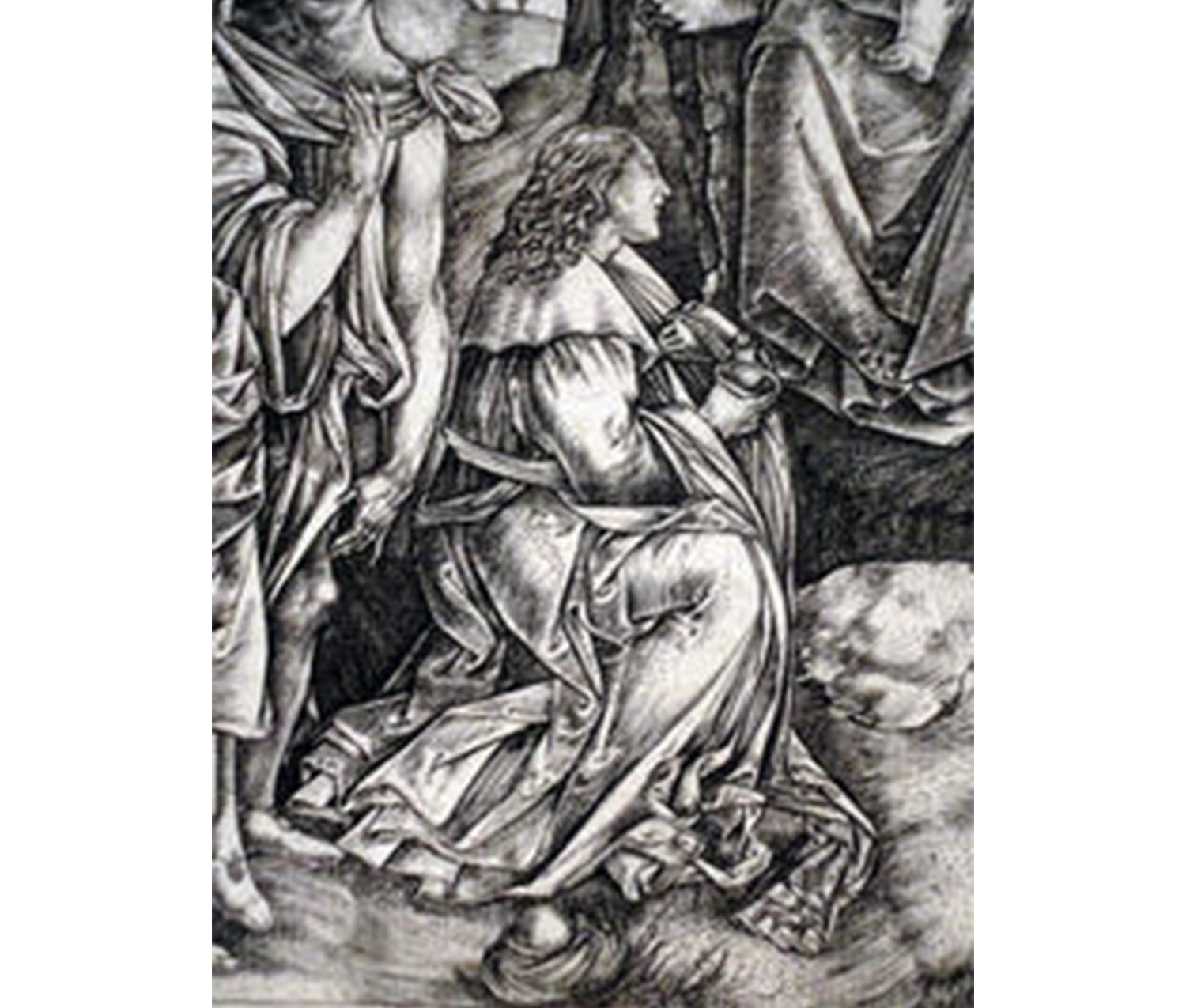

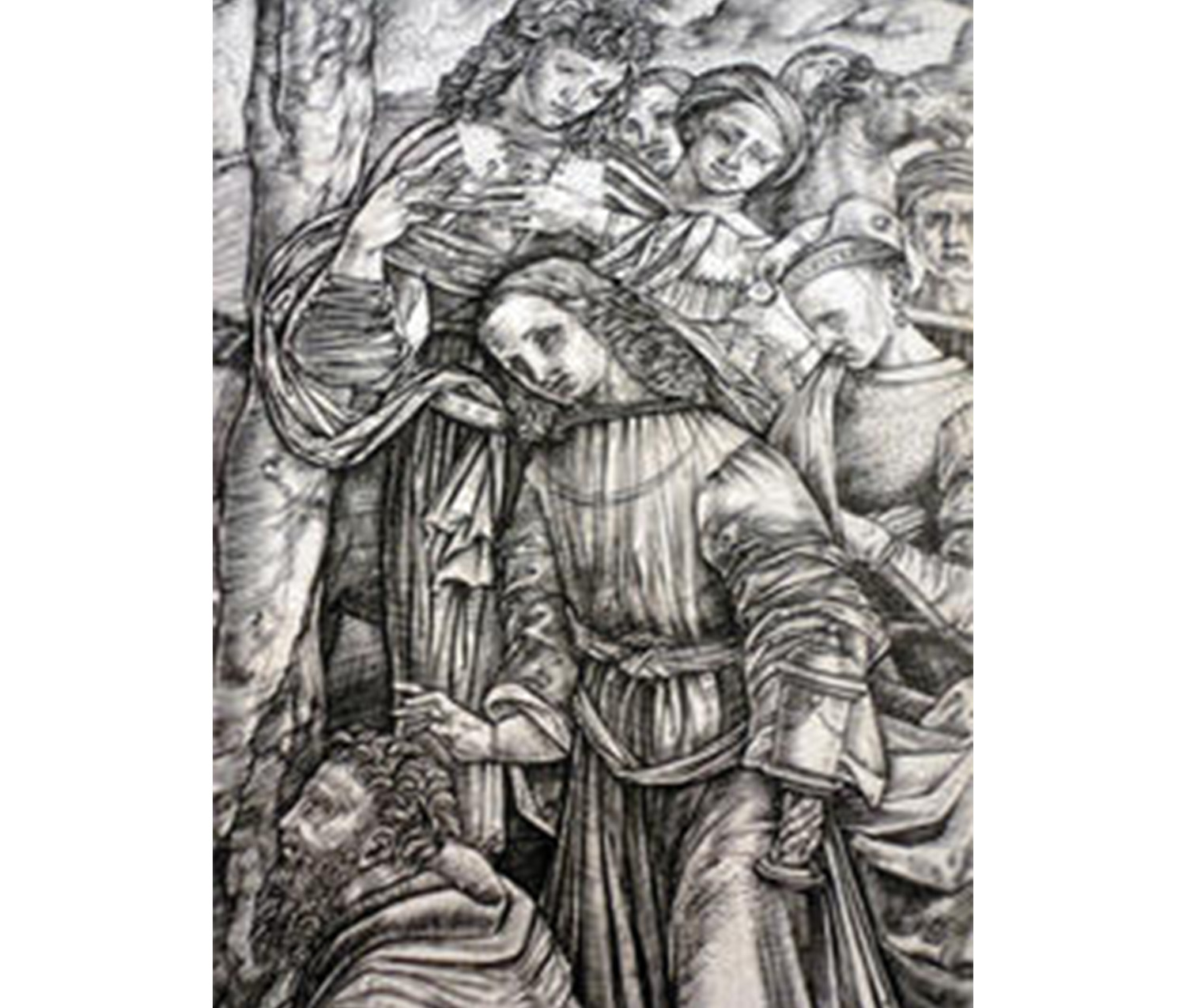

The Adoration of the Magi was a popular subject for Italian artists because it allowed the artist to showcase their ability to create an elaborate composition filled with animals, sumptuously clothed figures, and often a vast landscape. While Robetta does all of these things somewhat successfully, a closer examination of the print reveals the unabashedly referential nature of his work. The composition and many of the figures are directly borrowed from Filippino Lippi’s Adoration of the Magi (1496), now in the Uffizi Gallery, in a manner which raises questions about the relationship between the painter, Filippino, and the engraver, Robetta. Rather than creating an exact copy of the entire painting, Robetta’s print contains several mirror-image imitations of Filippino’s figures — particularly the kneeling Kings and the long-haired figure on the right, thought to be a portrait Lorenzo de Medici, the young cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent, from whom a crown is being removed (see details below). Other figures in the foreground are reminiscent of those in Filippino’s painting, but with slight variations of clothing, expressions, and gestures. Both works exhibit a centralized composition surrounding the Holy Family, yet Robetta creates a more unified arrangement by eliminating several figures seen in Filippino’s Adoration, including two members of the Medici family which appear in the left foreground of the painting. Although the painted Adoration was completed for the Convent of San Donato agli Scopeti at least five to ten years before Robetta’s print, scholars believe that these deliberate and discriminatory quotations of Filippino’s work point to the fact that Robetta worked from Filippino’s preparatory drawings rather than the finished painting. Whether Robetta worked in Filippino’s studio or acquired his drawings independently is unknown, but this shared relationship between painter and engraver was certainly not uncommon.

Detail from The Adoration of the Magi. Photograph by Julie Warchol.

Detail from The Adoration of the Magi. Photograph by Julie Warchol.

Detail from The Adoration of the Magi. Photograph by Julie Warchol. This figure is thought to be a portrait of Lorenzo de Medici, the cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

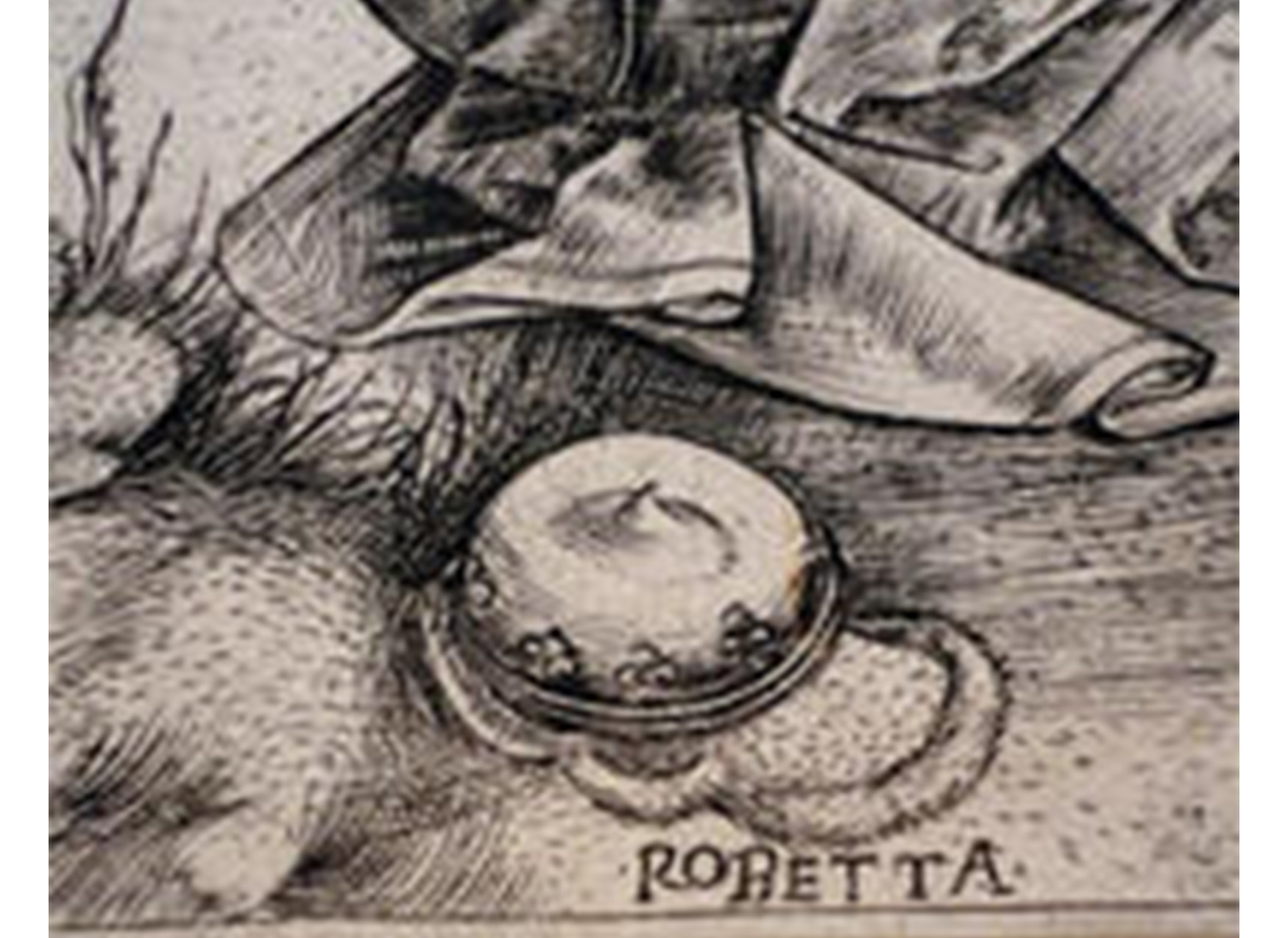

Robetta was an artist with diverse influences; he not only culled figures from many of Filippino’s paintings throughout his career, but also integrated elements of Northern printmaking, which was beginning to impact Italian artists at this time. In his Adoration, Robetta references Albrecht Dürer in his landscape of rolling hills and bulbous tree forms. A more subtle allusion is the small hat at the bottom of the print, directly above Robetta’s signature (see detail below), which is a direct quotation from Martin Schongauer’s engraving of the same subject. Although Robetta’s work is often deemed stylistically amateurish and naïve because of the late start to his artistic career, the true value of his engravings lie in how they illuminate the popular tastes at the beginning of the 16th-century, and offer modern viewers insight into the liberties of quotation taken by Renaissance artists.

Detail from The Adoration of the Magi. Photograph by Julie Warchol.