Silverpoint: Metal on Paper

Guest blogger Maggie Hoot is a Smith College student, class of 2016, with a major in Art History and a Museums Concentration. She is a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

The history of the graphite pencil stretches back to the mid-16th century in Europe. Before the wide availability of pencils, silverpoint was a very popular medium for creating reasonably permanent sketches and drawings (charcoal and chalk were both available, but not very stable over time). Silverpoint was used as early as the 12th century for both record keeping and the creation of art. In this medium, a line is produced by pressing a metal stylus (most often silver, but also gold, copper, and lead) to a specially prepared surface. In the early 15th century, the artist Cennino Cennini wrote Il Libro dell'arte, a how-to guide for Renaissance art creation. He recommended using a paste that included burned and ground fowl bones applied to paper, although many other methods were used.

Detail of Dieric Bouts' Portrait of a Young Man

In the Renaissance, silverpoint drawings were not considered completed works of art, and the medium was typically used in preparatory sketches for a painting. It was also used as a common starting point in the education of young artists. It taught them how to draw with precision and patience before they moved on to more advanced media. Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Durer were both taught in and taught their students via silver point.

Silver point was a difficult medium to master because you could only produce one shade, no matter how much force was applied to the stylus. Also, it could only be used on specially prepared ground and was impossible to erase. In comparison to the chalks and inks that were gaining popularity at the time, silver point had the advantage in terms of precision. Chalk had an added disadvantage in that it was easy to smudge.

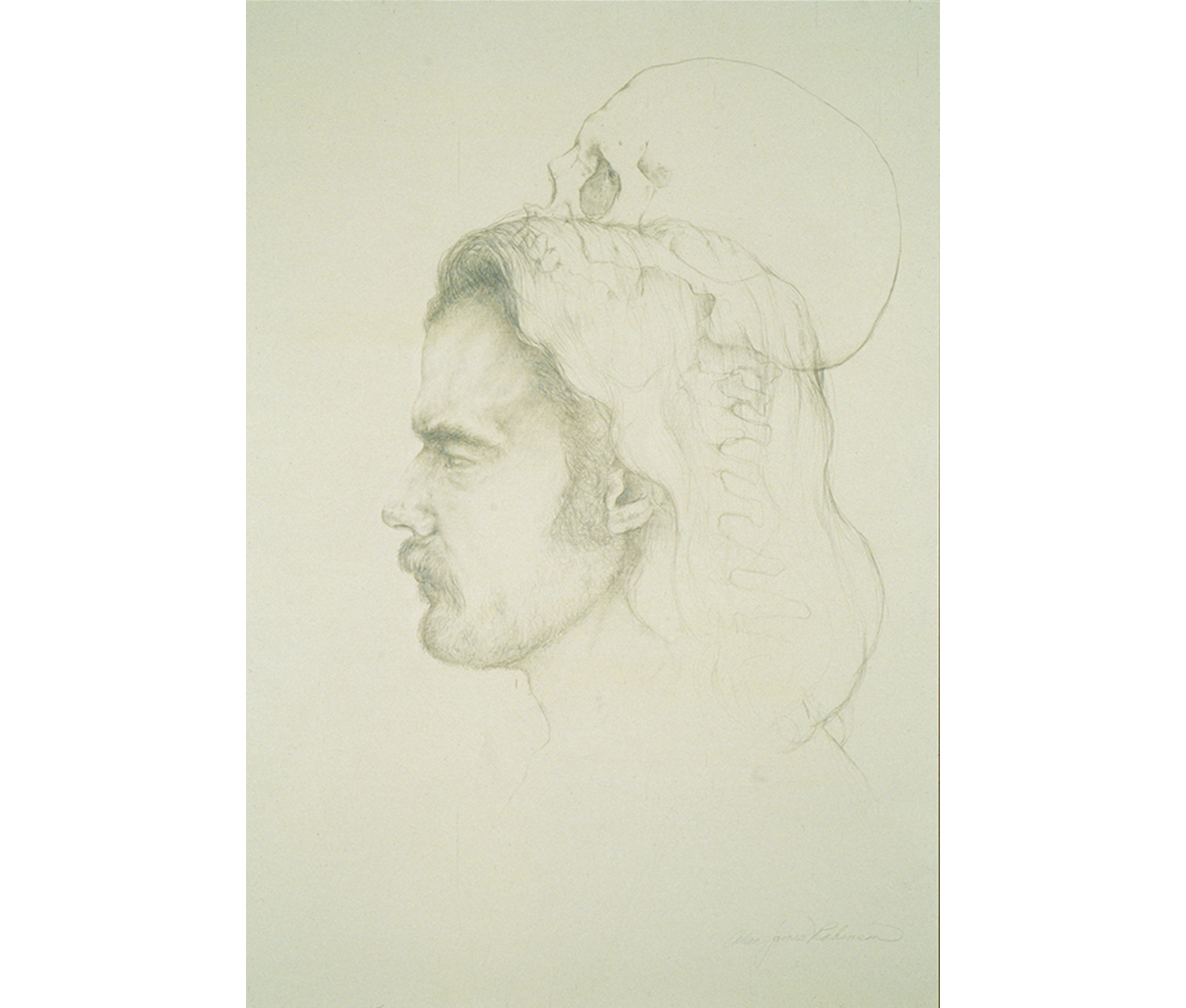

Alan James Robinson. American, born 1950. Self-Portrait, n.d. Metal point on treated paper. Gift of Priscilla Paine Van der Poel, class of 1928. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1983.44.30.

The creation of the graphite pencil changed everything. The markings were relatively permanent, yet could be erased. A fine, even line could be created with little effort. By the 1600s graphite pencils had completely replaced silver point in just about all applications. Silverpoint was rarely used and works in silverpoint were largely ignored. However, a few artists educated in silver point, such as Rembrandt, still used the medium occasionally. Thanks to the inherent permanence of silverpoint, many works from the Renaissance are still in fairly good condition.

There were several minor revivals of the artistic use of silverpoint in the succeeding centuries.

The first occurred in England in the 1800s with several of the Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Frederic Leighton. There was another revival in the early 20th century associated with Joseph Stella. He was an American modernist artist and draftsman. He once described silverpoint as “the clearest graphic eloquence.”

In the modern era, one of the challenges for creating silverpoint has eased as commercially prepared papers and styluses are available (of course, you can still prepare your own paper using one of the many recipes that can be found on the internet).