Smith Tours: Diego Rivera and the Value of Art

Guest blogger Maurine Collins Miller is a Smith College student, class of 2013, majoring in Art History and minoring in Spanish. She is a Student Museum Educator at the Smith College Museum of Art.

Designing and giving a tour at the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA) is both exciting and unpredictable. So when I was presented with a group of sixth graders who had been studying Mexican culture, I decided to focus the tour around the SCMA’s Diego Rivera works. Rivera is generally interesting to kids since he is such a famous artist with a very aesthetically approachable style. For this particular tour, the Museum’s collection spanned beyond the paintings typically associated with Rivera; the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs is home to an impressive collection of works on paper by the Mexican artist. With some advanced planning, we were able to view a selection of these prints and drawings depicting a variety of daily life scenes and portraits. With a reasonable amount of knowledge on Rivera, I felt confident that I could answer almost any question and build off of what the kids already knew. As a tour guide, however, you can never fully prepare for what the kids will ask about the pieces.

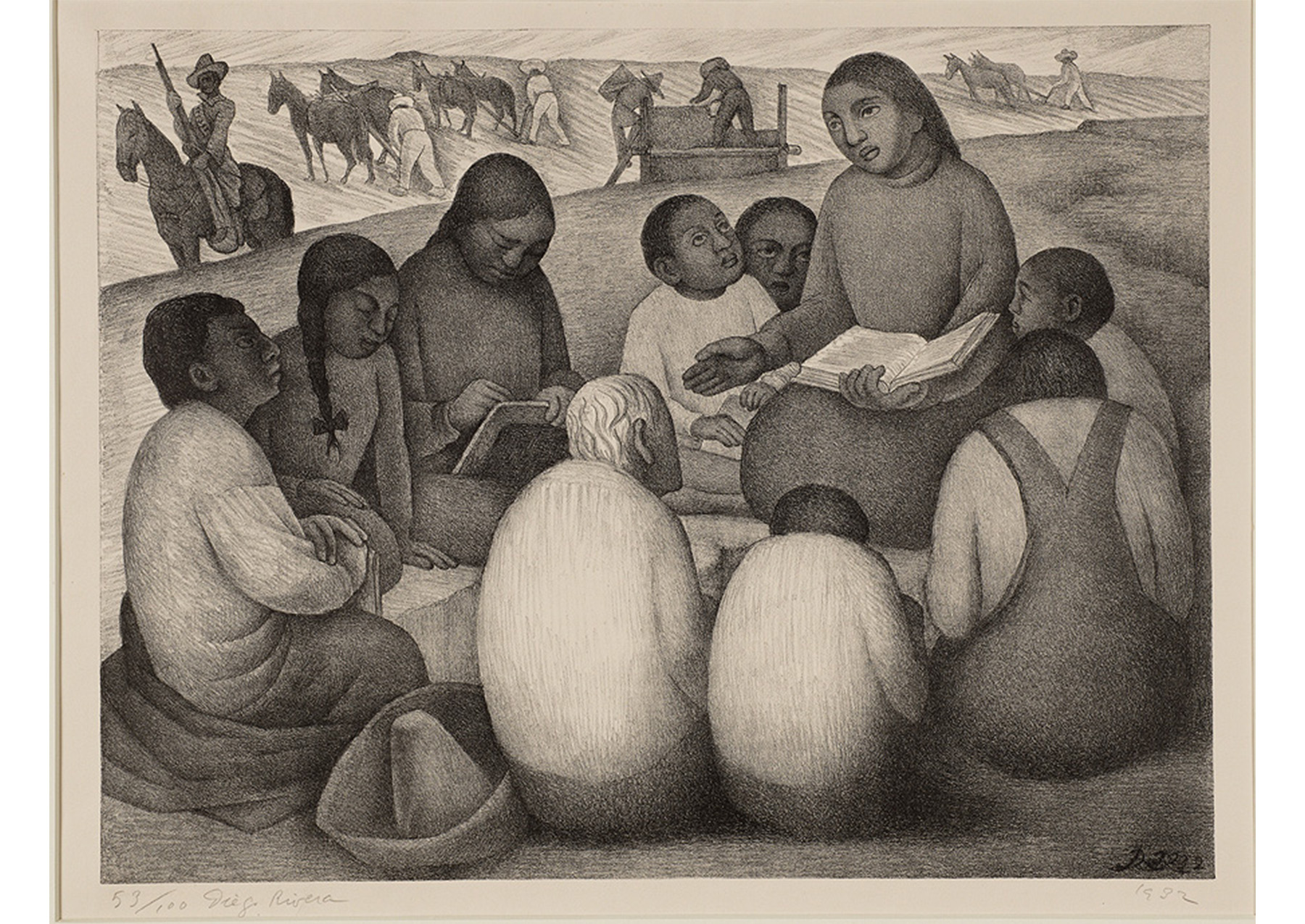

Diego Rivera. Mexican, 1868–1956. Reading Lesson, 1932. Lithograph printed in black on Rives wove paper. Gift of Selma Erving, class of 1927. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1972.50.95.

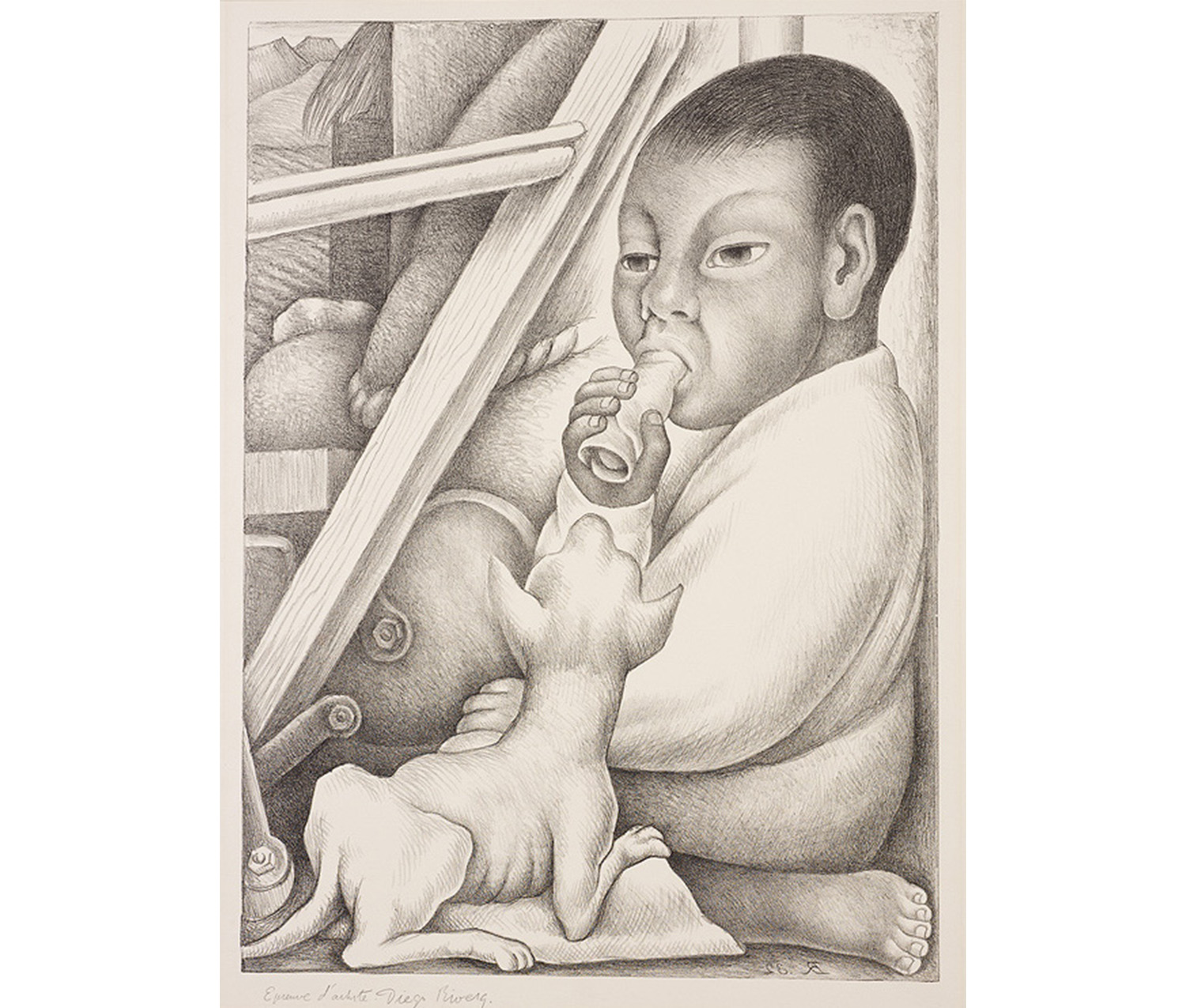

Much to my surprise, the students were more interested in the monetary value of Rivera’s work than what they looked like. Why and how art is valued is fascinating -- I don’t blame them for inquiring as to the value of the pieces. Unfortunately, I was prepared to talk about culture and why Rivera might have made some stylistic choices. I formulated an explanation “on the fly” to direct the discussion away from the monetary issue: when artworks are acquired by or donated to a museum, the purpose is not to put a price tag on them. Since museums build their collections based on what they’d like to show and conserve forever, accessioning works into a collection almost negates any monetary value. Their “worth” is not about money.

Diego Rivera. Mexican, 1868–1956. Flower Festival, 1931. Lithograph printed in black on cream laid paper. Gift of Elizabeth Langmuir (Elizabeth Cross, class of 1931), transferred from the Rare Book Room. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1980.39.19.

Sixth graders, however, are persistent. Thus, when they continued asking me about how much all of the Diego Rivera works on paper are collectively worth, “even if I was just guessing,” I explained that value is more than a monetary concept. Value also means how a work enhances a collection and, particularly in a teaching museum like SCMA, can be compared with other pieces for educational purposes. Value and price are not mutually exclusive.

I was eventually able to re-route the discussion back to Mexican culture, and the students finally settled into appreciating how amazing the SCMA and the Cunningham Center are. After all, how special is being in a room with only fifteen people and ten impressive works on paper—not behind glass or framed—from such a phenomenal artist? Now that is a valuable experience.

Diego Rivera. Mexican, 1868–1956. Boy with Dog, 1932. Lithograph printed in black on Rives wove paper. Gift of Selma Erving, class of 1927. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1972.50.96.