In Space

Guest blogger Petru Bester is a Smith College student, class of 2015, with a major in Art History. She is a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

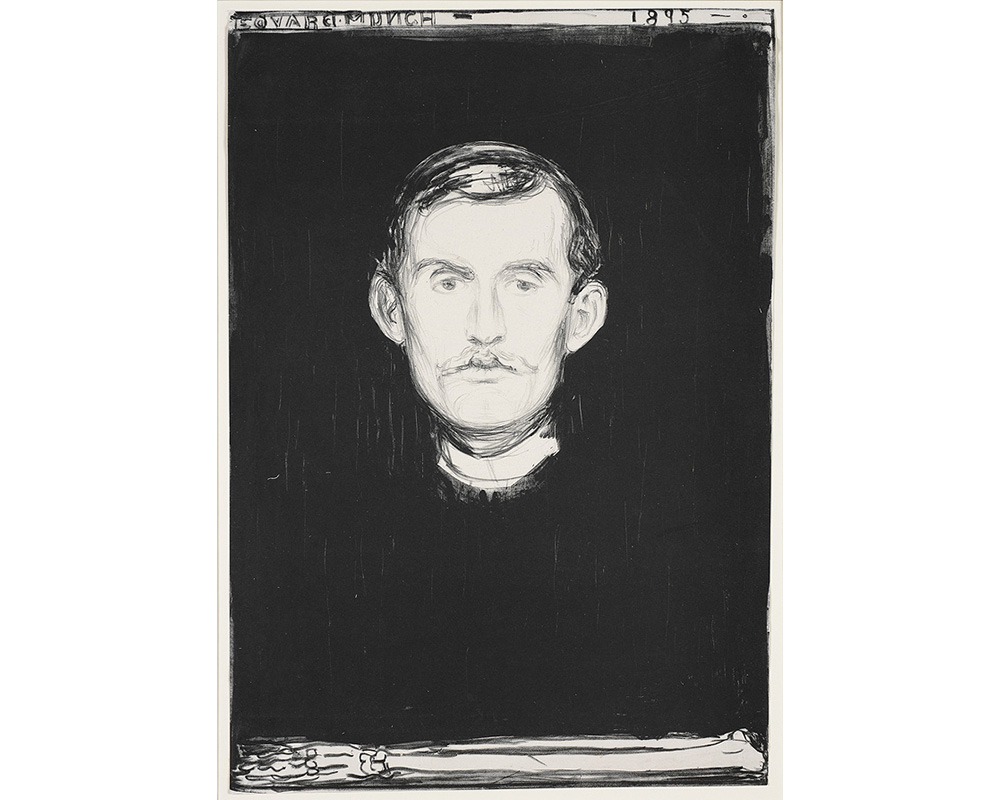

Existence envelopes every living creature on earth; its contemplation however is a uniquely human experience. Scholars, philosophers, writers, and artists have concerned themselves with the principles of love, life, and death for millennia. Painter and print maker Edvard Munch was no exception. A Norwegian artist active in the latter half of the 19th century most famous for his painting The Scream, Munch exploited these concepts in hopes of understanding and displaying the human condition to his audience.

To Munch the human condition was tragic. Experiencing the “traumas of life” at an early age Munch declared that: “Disease, insanity, and death were the angels that attended my cradle, and since then have followed me throughout my life.” Plagued by illness himself, Munch as a child witnessed his mother and older sister succumb to tuberculosis. After their deaths Munch’s father suffered through periods of mental illness. As an adult Munch found little success in his relationships with others especially those he had with women. Being a member of such anti-bourgeois clubs like the Kristiania Boheme, Munch took to a life style of drinking and sexual liberation. In doing so Munch lost or strained most of his relationships and was often abandoned by his lovers.

Munch’s body of work went through several phases of experimentation but most pieces adhered to his lost sense of self and melancholic understanding of life. In the mid 1890s Munch started producing prints; up to this point he was mostly a painter. The woodcut prints made during this time simplified Munch’s motifs and limited his color palette. These pared down images are strikingly powerful and exemplify Munch’s commentary on human emotions and interactions.

The print Meeting in Space from 1899 caught my attention as I browsed through the museum’s print database. Made from one block of wood cut like a jigsaw into three main pieces, the print is unremarkable at first. The two human figures in green and red stand out in stark contrast to the black background. Its minimalism turns into something of beauty after a moment and as a viewer I felt overwhelmed by a sense of anxiety. The figures (one female and one male) seem to be weightless and effortlessly float toward one another, meeting awkwardly in the center of the frame, while their ridge bodies in comparison seem to disconnect the two from each other. The print speaks to Munch’s feeling toward women and the relations of love he experienced within his own life.

Edvard Munch. Norwegian, 1863–1944. Meeting in Space, 1899. Woodcut printed in red, green and black from one block cut into three pieces on China paper. Gift of Selma Erving, class of 1927. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1972.50.71.

To him women were cruel and used their bodies to manipulate and destroy men, and Munch represents this by the positioning and coloring of the female figure. Her figure in cool green is overtly sexualized, putting her body on display. She props her head on her left arm and rests her right on her hip. Her long hair flows behind her as she faces the viewer.

Detail of woman resting head on arm in Meeting in Space

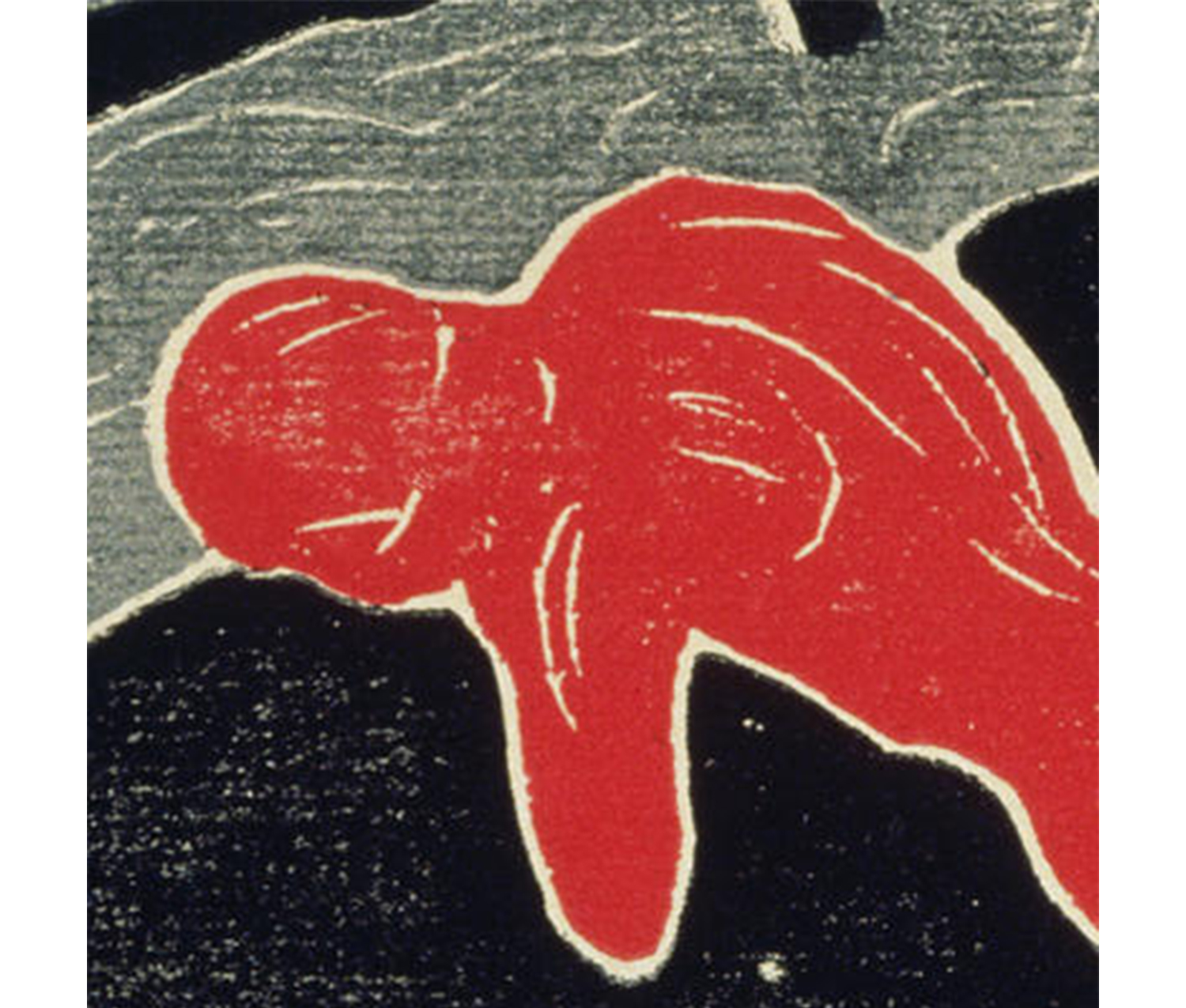

The male, seen as a “victim”, is passionate and loving, as displayed through his respective positioning and coloring. He is in warm red and faces away from the viewer in a more closed position. An obvious sexual and emotional tension is created between the two. The carved sperm surrounding the couple amplifies the sexuality of the piece.

Detail of male head turned away in Meeting in Space

Beyond the tension presented in this print, Munch makes known to the viewer his thoughts of human purpose and the state of the living. Rejecting Christianity as a part of the Bohemia movement, Munch did not view the afterlife as a sanctuary for the dead. Death was final and the natural end stage to our lives. In life we have no purpose or God to adhere to; instead we merely float in space. This for me holds much resonance during this New England fall. The leaves that were once cool green burn with red and orange for our viewing pleasure before they die, detach, and rot. The print has takes on a poetic quality that leaves me questioning my own human relationships and condition of life.