Thomas Cornell's French Revolutionary Portraits

Guest blogger Jennifer Guerin is a Smith College student, class of 2014, majoring in American Studies and History with focuses in Public History and Social Movements. She is a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

The SCMA’s Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs has in its collection a set of etchings that artist Thomas Cornell completed for the Northampton-based Gehenna Press, run by Leonard Baskin, in 1964. The book for which they were produced, The Defense of Gracchus Babeuf Before the High Court of Vendôme, is a French text from 1797 translated by John Anthony Scott, a professor of History at Amherst College. The works were donated to SCMA by Scott and his daughter, Elizabeth.

François-Noel Babeuf took the name Gracchus as a reference to Roman tribunes Tiberius and Gaius Gracchi, famous for advocating land redistribution. As his choice of name suggests, Babeuf was the leader of a radical left wing faction of French revolutionaries who believed in policies such as division of lands, progressive taxation, and free and equal public education. These revolutionaries opposed the Directory and the government established by the Constitution of 1795, wanting instead to return to the more democratic-minded Constitution of 1793, and they attempted to foment a rebellion. Babeuf’s defense was given over the span of three days, and though it did not prevent his execution, it is particularly interesting because it does not attempt to deny the accusations, but instead argues that their action could not be considered conspiracy because they operated under the principle that opposition intended to remove an unjust government is always legitimate. Additionally, it is worth noting that Gehenna Press’s choice to publish a text which praised a socialist figure was a fairly radical move in Cold War America. Cornell’s twenty-one illustrations represent the major players in the trial, as well as other important figures of the Revolution. During his professional career, much of Cornell’s work focused on social justice issues, and these etchings are the predecessors of that work.

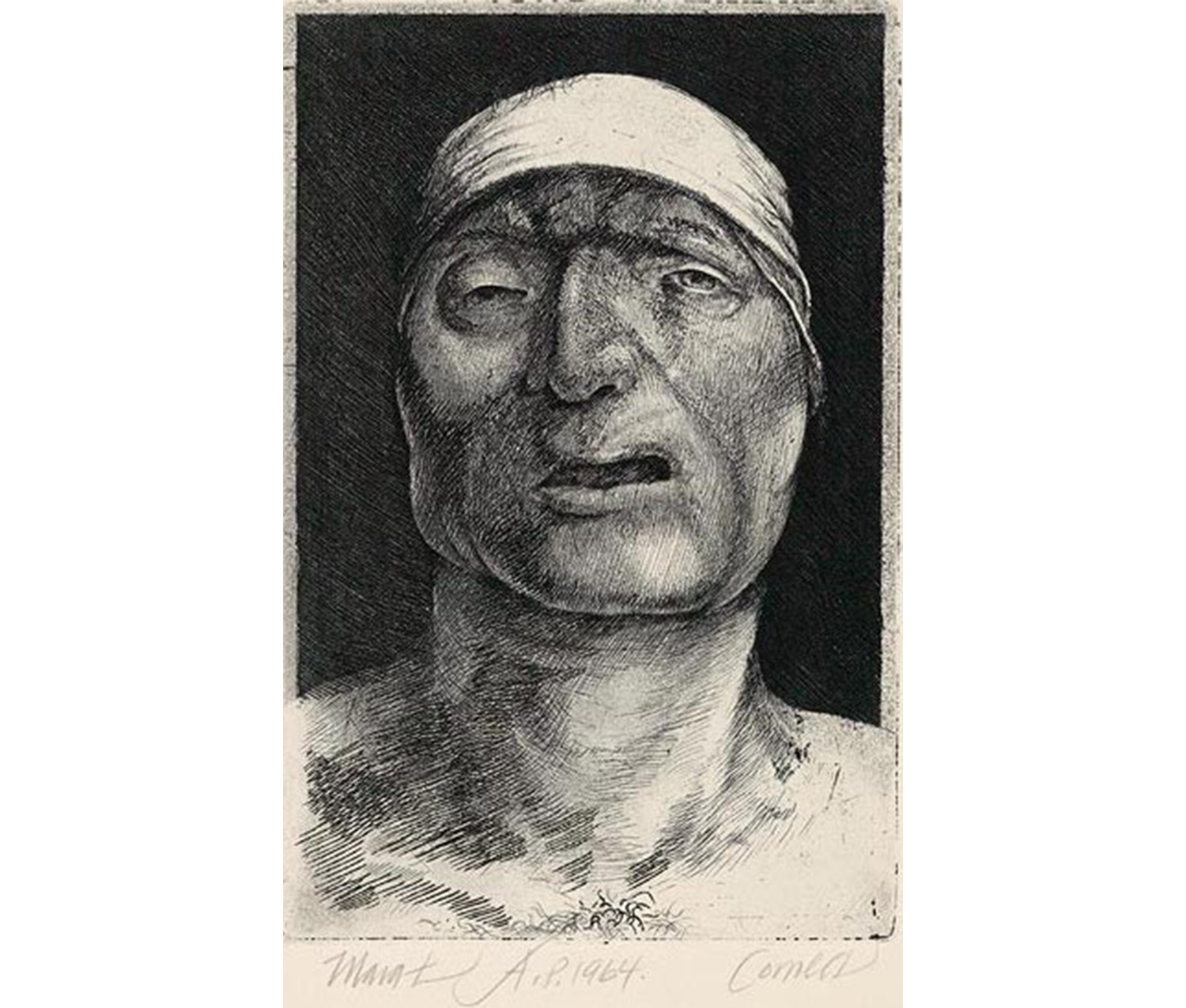

Thomas Cornell. American, 1937–2012. Marat from The Defense of Gracchus Babeuf Before the High Court of Vendôme, 1964. Etching printed in black on paper. Gift of Elizabeth and John Scott. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2008.62.17.

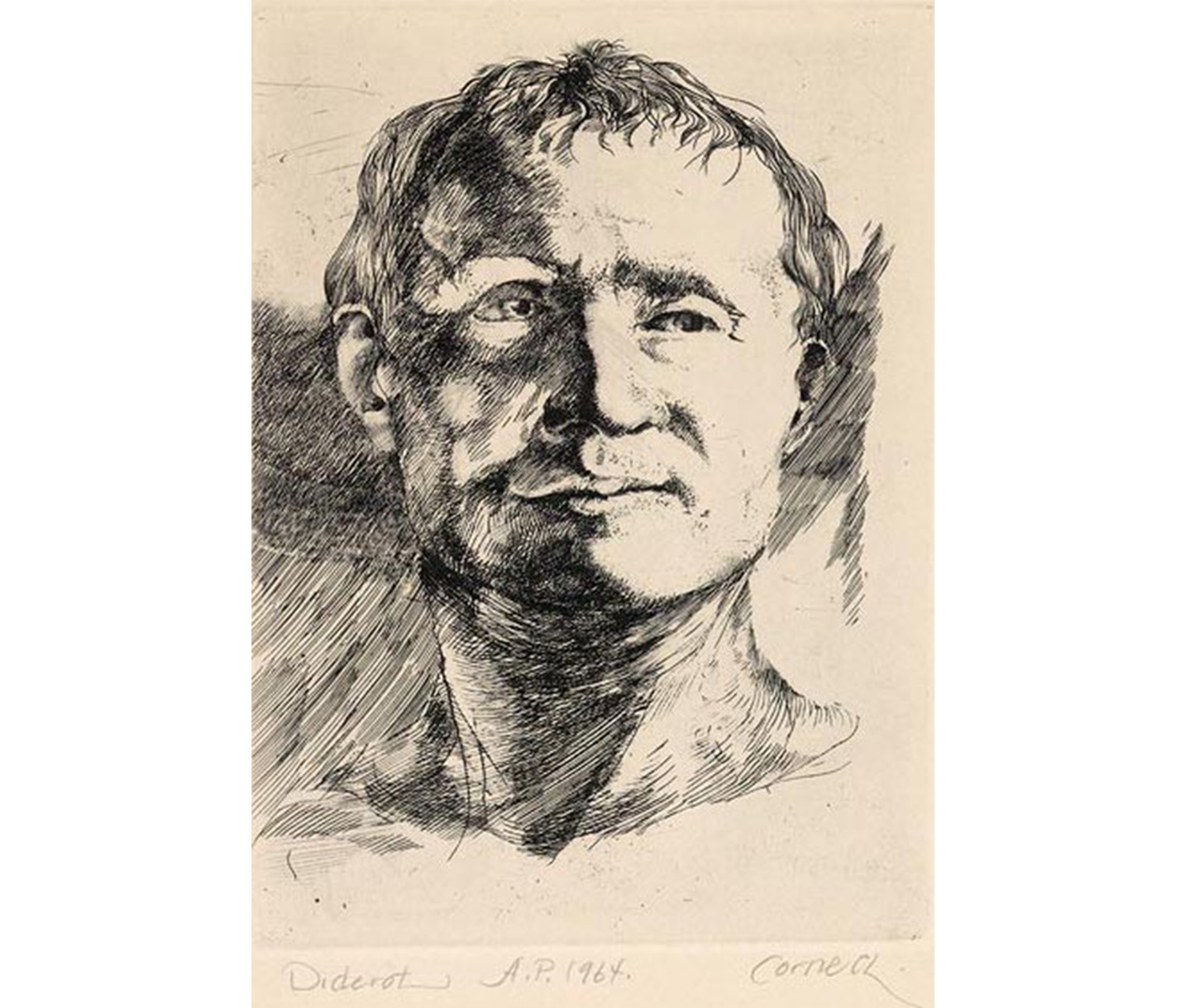

In creating these French Revolutionary portraits, Cornell referred to previous representations of the individuals but did not hesitate to reinvent the images. For instance, his portrait of Jean-Paul Marat works to present an alternative to the idealized images of Marat, most notably Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting The Death of Marat. While in David’s painting, Marat’s physical deformities and debilitating skin condition are only hinted at by his bandaged head and the bathtub he sits in, Cornell’s Marat is clearly deformed and appears grotesque. In his portrait of Diderot, Cornell’s transformation goes in the other direction— the Diderot shown in portraits becomes an idealized figured seemingly modeled after a Roman emperor. This allows the portrait of Diderot to represent not only the inspiration that the revolutionaries drew from Enlightenment figures, but also the huge influence of Greek and Roman history.

Thomas Cornell. American, 1937–2012. Diderot from The Defense of Gracchus Babeuf Before the High Court of Vendôme, 1964. Etching printed in black on paper. Gift of Elizabeth and John Scott. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2008.62.11.

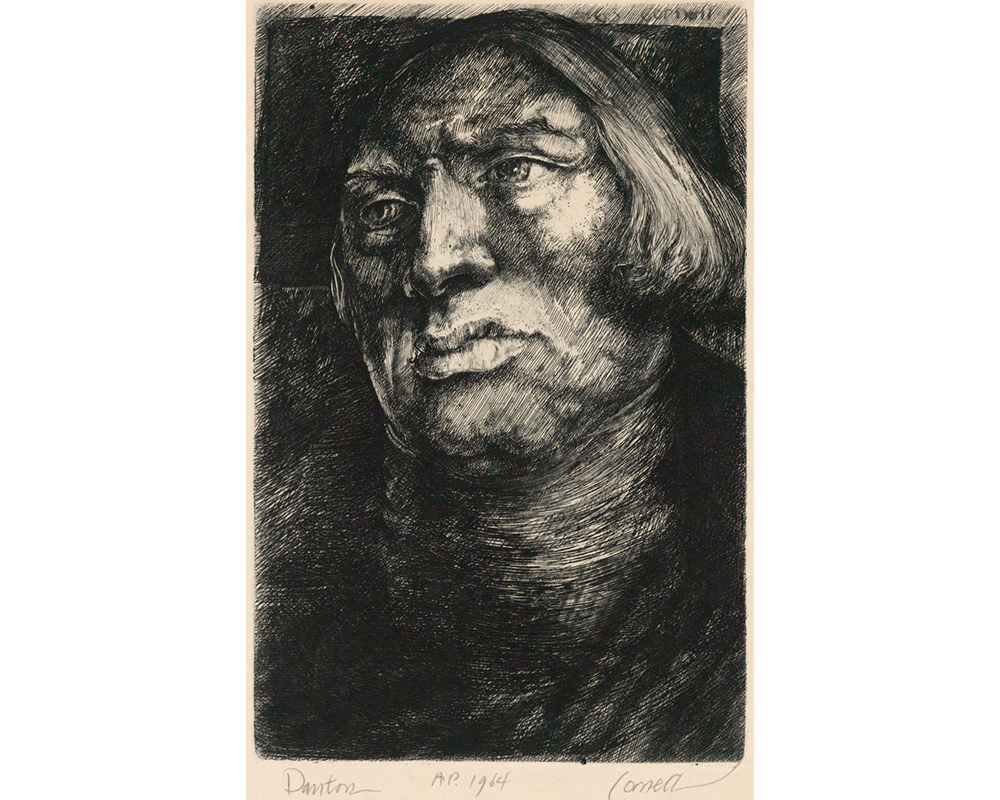

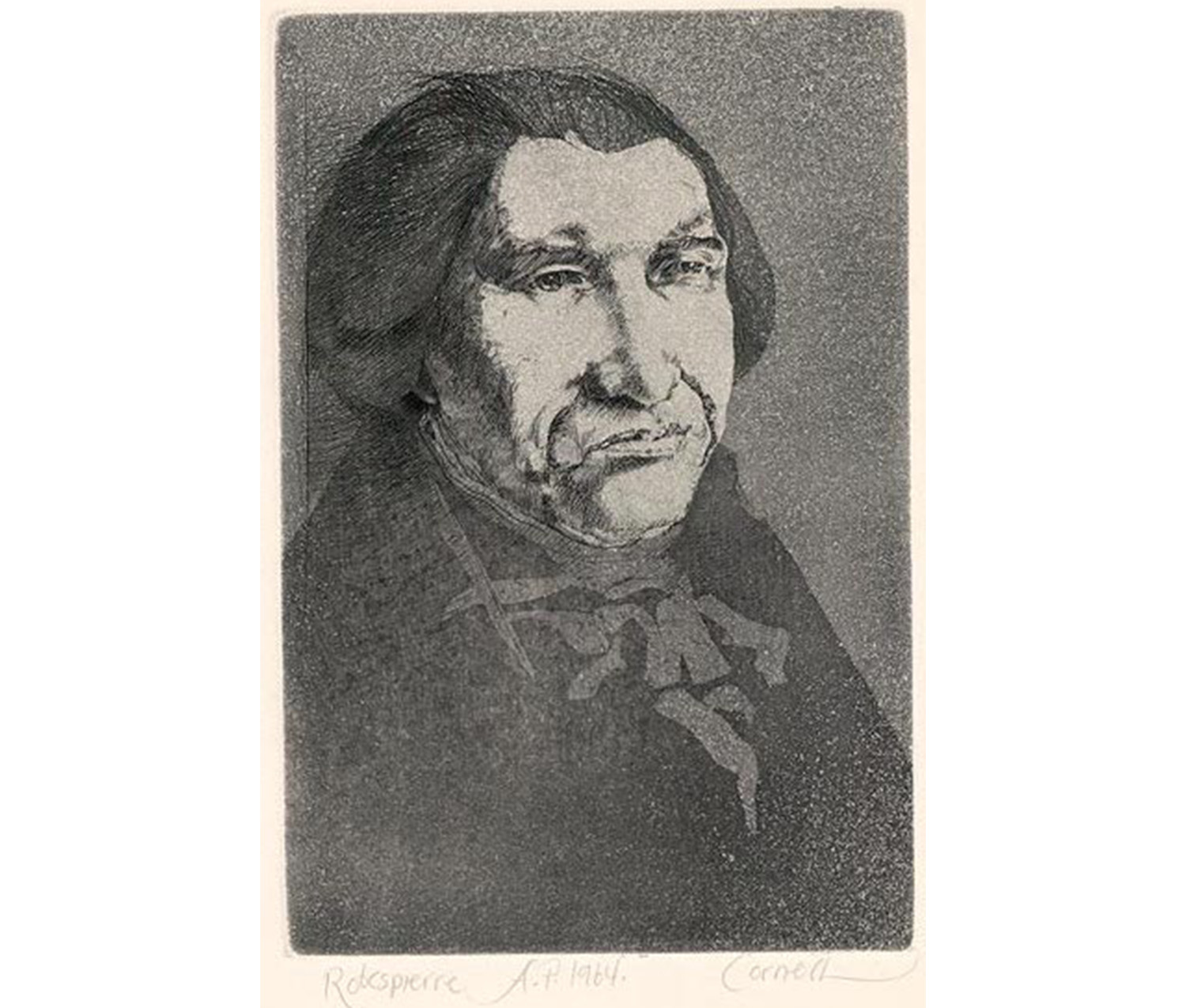

Finally, Cornell’s images of Danton and Robespierre, two of the most controversial figures of the Revolution, depart from the conventional, neoclassical portrait to show two very human and conflicted figures. While Robespierre is nearly always show wearing a powdered wig, which was mocked by opponents as too aristocratic, Cornell’s image eliminates the wig, thereby making him appear more vulnerable and closer to the common people. In the portrait of Danton, Cornell’s use of light surrounds Danton with a sense of power and emotion, and his facial expression suggests an intense personal conflict.

Thomas Cornell. American, 1937–2012. Robespierre from The Defense of Gracchus Babeuf Before the High Court of Vendôme, 1964. Etching printed in black on paper. Gift of Elizabeth and John Scott. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2008.62.4.

Thomas Cornell (1937–2012), professor and artist, devoted much of the early years of his artistic career to drawing and etching, though he is generally well known for his paintings. Following his undergraduate work at Amherst College (B.A. 1959) and graduate work at the Yale School of Art and Architecture (1959–1960), Cornell explored the field of bookmaking, completing illustrations for Apiary, the Smith College student press, as well as Gehenna Press. He also founded his own publishing house in 1964, Tragos Press, through which he produced a number of publications relating to the Civil War, abolition, and the Civil Rights Movement. In 1962, Cornell was hired to establish a visual arts program at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, and he would continue to teach there until he retired in June of 2012, shortly before he passed away in December.