Vanguards of Ukiyo-e: The Women of Modern Japanese Printmaking

Guest blogger Nicole Bearden AC '19 is a Smith College student and Ada Comstock Scholar with a major in Art History and a Museums Concentration. She was a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

When most people envision Japanese woodblock prints, images by Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Utamaro often come to mind. These great masters of ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) were incredibly prolific, and educated generations of artists via their ateliers--workshops in which multiple artists and assistants worked and were trained. While these men were certainly experts, their images of Japan’s “Floating World”--beautiful women, Kabuki, landscapes, and illustrations of folktales--are not the sole interpretations of this popular art form.

During the early modern period (17th-early 19th centuries) there were very few female professional artists. Women were excluded from the guilds of professional painters who worked in the ateliers. Japanese society at the time had firm expectations that women conform to the role of mother, wife, and household manager. During the Tokugawa Shogunate (1602-1868) women did not even legally exist as individuals. They were considered subordinate to men, and could not own property. A woman living as an artist was seen not only as an anomaly, but as an affront to Japanese society.

Katsushika Hokusai. Japanese, 1760–1849. Ejiri in Suruga Province, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. ca. 1831. woodcut printed in color on paper. Gift of Mrs. Arthur B. Schaffner in memory of Louise Stevens Bryant, class of 1908. SC 1959:264.

Other Japanese art forms such as scroll painting and calligraphy increasingly included women during the 19th century, but the popular ukiyo-e ateliers were not as conciliatory. In these woodblock print workshops, there were very few women to be found, and those present were often the daughters, nieces, or granddaughters of the artists themselves (such as Hokusai’s daughter Katsushika Ōi). The limitations placed upon Japanese women would only be overturned after WWII, when Confucian-centric ideals were displaced by the the Civil Code of 1947. Through this code, women were granted legal equality with men, which included the rights to own property, vote, inherit from their families, and marry and divorce at will.

Iwami Reika. Japanese, 1927–2020. Morning Waves. 1978. Woodblock printed in black and metallic ink with embossing on medium thick, slightly textured, cream-colored paper. The Hilary Tolman, class of 1987, Collection. Gift of The Tolman Collection, Tokyo. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2014.12.15.

Although pursuing a career in art was still a struggle, it became a possibility for many young Japanese women who came of age during WWII, such as Iwami Reika and Naoko Matsubara. Still alive and working, these women, are considered trailblazers in the world of Japanese art. Their interpretations of the woodblock print run the gamut from floral and picturesque--reminiscent of the work of earlier masters--to abstract and minimalist.

Iwami Reika uses driftwood motifs and gold leaf to create a hybrid of earthbound and the celestial, often referencing water and the light of the moon or the sun. Her compositions evoke nature, rendered in various shades of black and white, then punctuated briefly with splashes of gold. Reika makes great use of negative space, balancing her final design as simultaneously resolute and delicate.

Shinoda Toko. Japanese, born 1913. Spring. 1978. Lithograph and handcoloring on heavyweight, moderately textured, white paper. The Hilary Tolman, class of 1987, Collection. Gift of the Tolman Collection, Tokyo Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2014.12.33.

Working in a similarly spare fashion, Shinoda Toko’s prints center around conceptual shapes and calligraphic methods. Unlike Iwami’s work, which is devoid of words, Toko uses text--or the illusion of text--and calligraphic brushwork to form abstract landscapes. The work Spring (1978), for example, is composed of bold, black strokes; the wide marks left by the brush create a structured, very linear view of nature.

An erratic diamond-shape creates the illusion of a winter field--white snow bordered by sterile hedges, their black color faded to reveal a gray-white underneath. In the bottom right-hand portion of the print, is a stiff tree, leafless in the dead of winter. These elements of the dormant life of winter are interrupted in the upper-left part of the composition by fine flourishes of deeper black and bright green, signifying the return of spring.

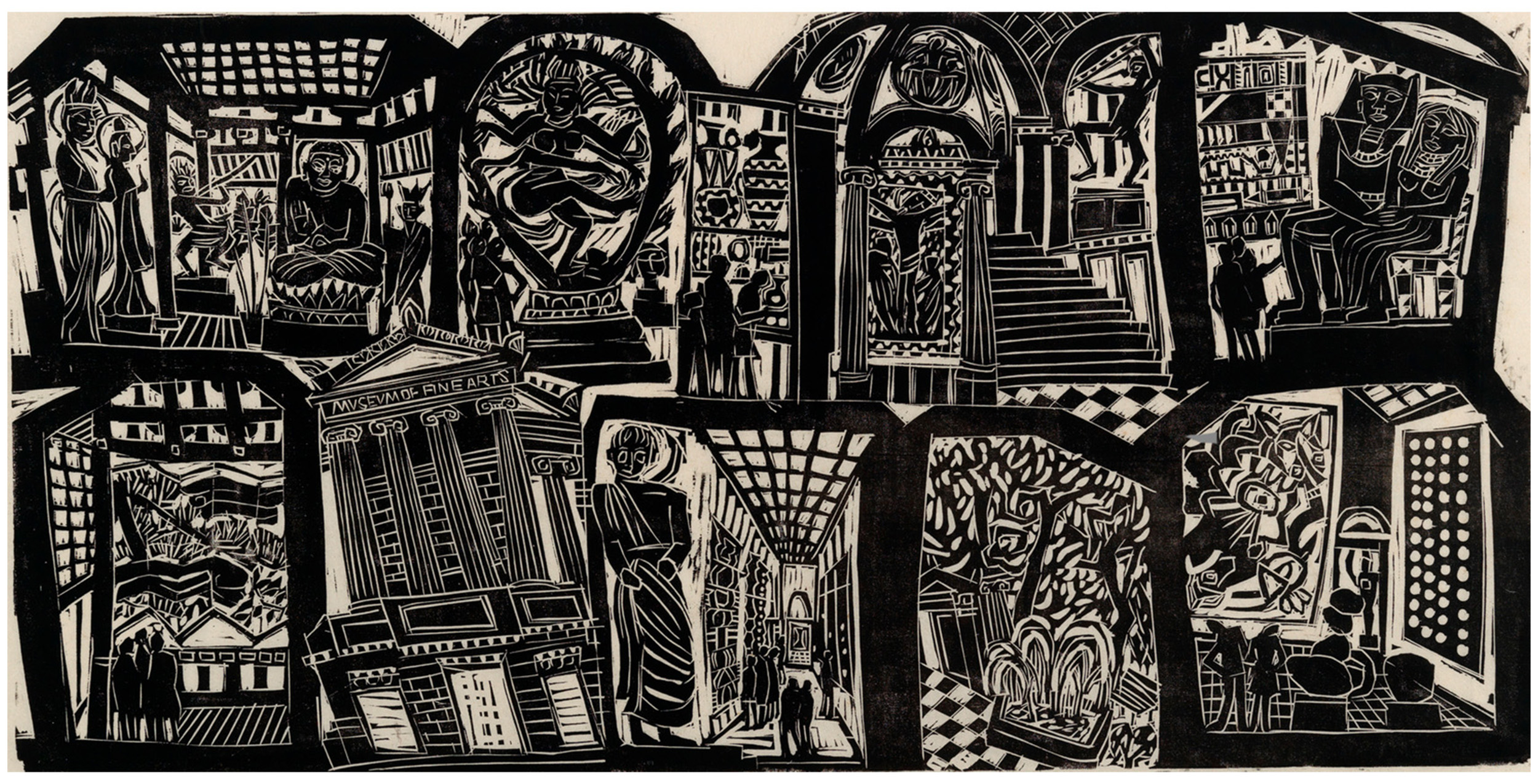

Naoko Matsubara. Canadian, born Japan, b. 1937. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. n.d. Woodcut printed in black on medium thick, slightly textured, cream-colored Asian paper. Gift of Joan Lebold Cohen, class of 1954, in honor of MFA colleagues Martha Manchester Wright, class of 1960, Sarah Griswold Leahy, class of 1954, and Sue Welsh Reed, class of 1958. SC 2012.80.

Naoko Matsubara’s work forcefully diverges from that of Shinoda and Iwami. Rejecting minimalism, her images crowd the page, resembling a haphazard, almost cartoonish rendition of modern life. In Matsubara’s woodblock print Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the viewer is presented with a cross-section of the museum, its contents, layout, and patrons, as if the side of the building had been neatly removed. The result, printed in bold black and white lines, draws attention to the multitude of cultures displayed and appropriated by BMFA--a serious issue playfully depicted by the levity of her style.

These women, who have embraced the art of ukiyo-e in the 20th and 21st centuries, differ widely in style from both the works of the famed forefathers of Japanese printmaking and one another. However, the influence of those who came before left a definite imprint, while the global exchange and rights gained for women after World War II allowed for development of the individual styles developed by these contemporary print makers.