The Viewer as Voyeur

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Cunningham Center manager and Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

The Smith College Museum of Art is dedicated to bringing out works on paper into the main galleries, where all visitors can see them. Since works on paper are more sensitive to light than other mediums, SCMA has installed special Works on Paper cabinets throughout the galleries for the display of prints, drawings and photographs. Today’s post is part of a series about the current installations of the Works on Paper cabinets, which will remain on view through August 2016. Henriette's previous post on this cabinet can be seen here.

Bénigne Gagneraux. French, 1756–1795. Jupiter and Antiope, 1787.

Ironically, the strictures that limited the way in which the female body could be shown also offered voyeuristic, titillating opportunities for the (presumably) male artist to exploit for the (presumably) male viewer. The “accidental” slip or placement of a garment or drapery could expose or accentuate bare flesh. The often-used trope of the back view of the female nude gave the illusion that the model had just turned away, making her “unaware” she was being viewed, and giving permission for the art lover/voyeur to stare.

Controversy

Artists could observe academic boundaries in representing the female nude but skirt them at the same time. For example, Ingres invoked the trope of the odalisque figure, used by Titian and many other artists, as an opportunity to display the female figure fully unclothed. In his Odalisque of 1842, the woman is placed in an exoticized harem setting, languidly lounging, with her gaze directed away from the viewer toward the slave serenading her.

In contrast, Edouard Manet’s Olympia of 1863 was based on the classical odalisque but breaks all the rules for the permissible visual presentation of the female nude. Manet contemporized the figure, making her a “real” rather than idealized woman who was recognized by the viewing public as a modern courtesan or prostitute gazing directly out at the viewer and waiting for her lover. This painting, when it was shown at the 1865 Paris Salon, shocked audiences and critics by its audacity.

Left: Edouard Manet. French, 1832–1883. Olympia, 1863. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Right: Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. French, 1780–1867. Odalisque with Slave, 1842.

Objectification of the Female Nude Body

While avant-garde artists embraced modernity by showing actual rather than idealized female bodies in contemporary settings, women were still objectified in art as they were in society.

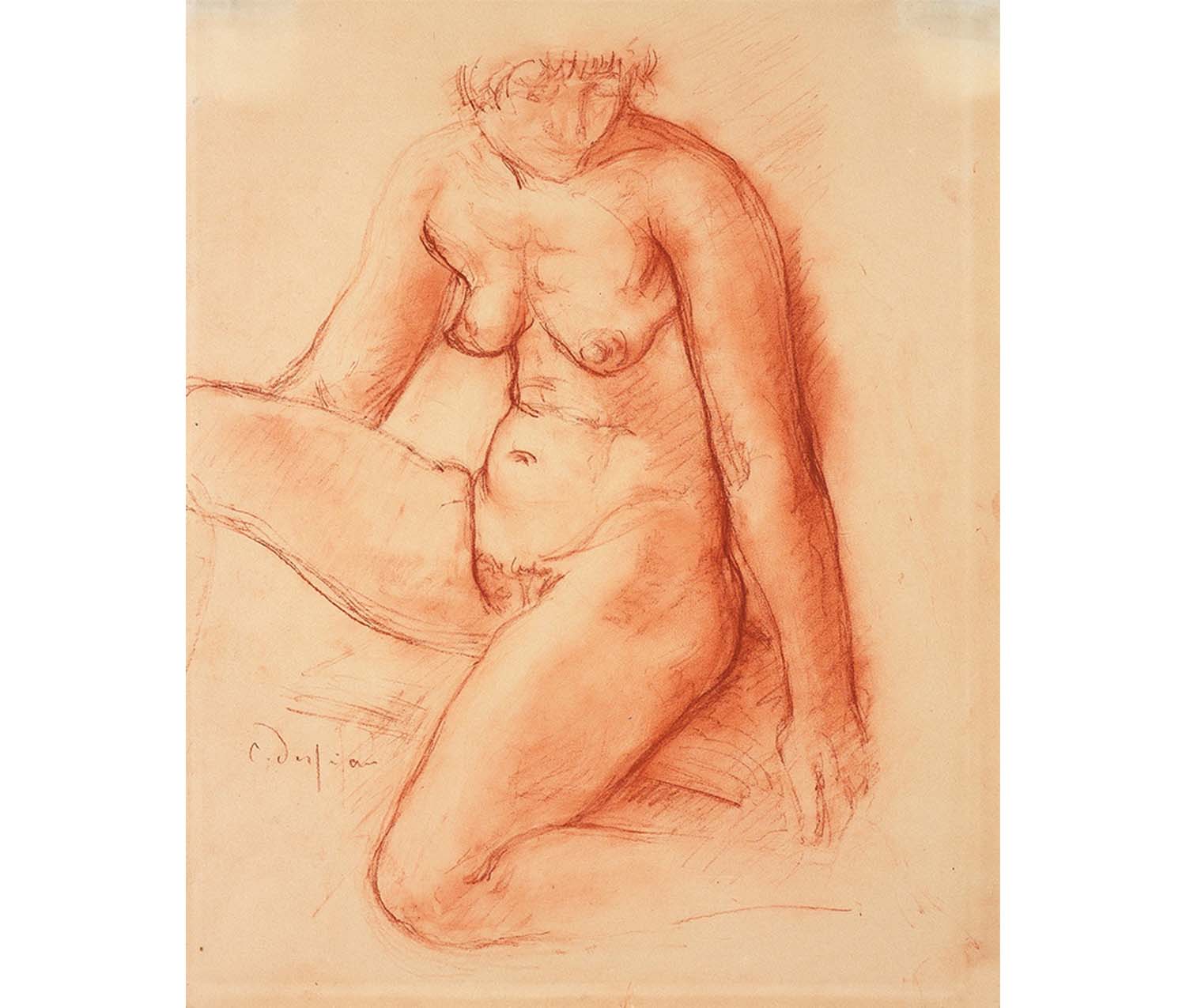

Charles Despiau. French, 1874–1946. Seated Nude, n.d. Red crayon on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Barr Jr. SC 1968.26.

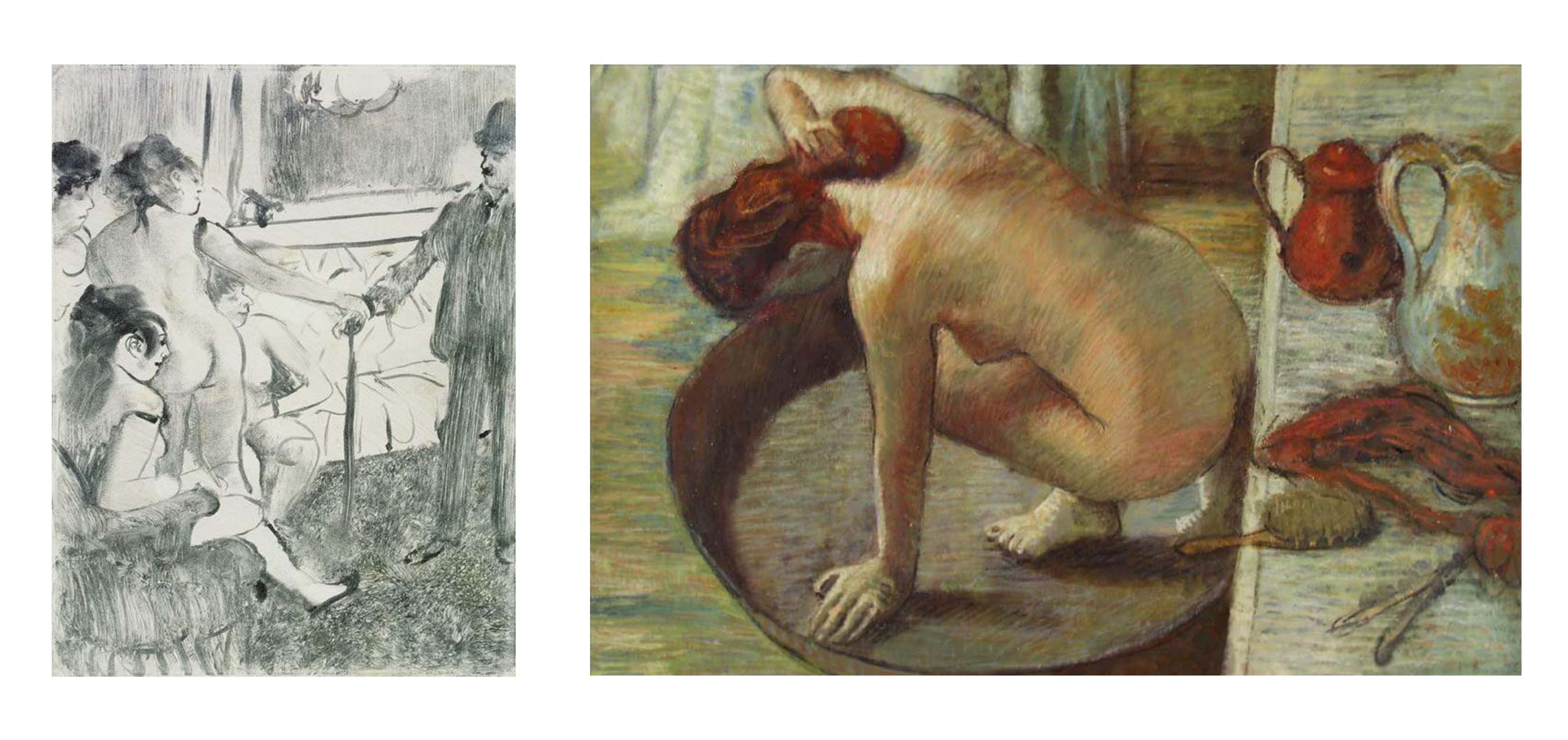

However, the famously acerbic artist Edgar Degas, who often portrayed the female nude, depicted bathers who were awkward rather than enticing and prostitutes who were shown in frank engagements with their clients. While these portrayals may not have been entirely sympathetic to their subjects, they represent a change in the representation of the female body.

Left: Edgar Degas. French, 1834–1917. The Serious Client, 1876–77. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Right: Edgar Degas. French, 1834–1917. The Tub, 1886. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.