Xu Wenhua 徐文华

Guest blogger Kayla A. Gaskin is a Smith College student, class of 2017, majoring in East Asian Languages and Literatures. She is a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

As an East Asian Languages and Literatures major in the Chinese concentration, I am interested in exploring the Cunningham Center’s collection of Chinese art. Recently, I became drawn to an artist named Xu Wenhua, whose prints are bright and reminiscent of the Cultural Revolution’s propaganda posters but possess a somewhat somber aura. The Center has five of Xu’s works – gifted by Andrew Kim and Wan Kyun Rha Kim, class of 1960. Unfortunately, this was all the information on Xu Wenhua’s work I could find. Xu himself is also a bit of mystery, entirely absent from Smith’s library resources, but I managed to retrieve some details. Xu Wenhua appears to be a Shanghainese art teacher who later on travelled to the United States for personal study. While I was glad to find at least a little insight into Xu’s background, this did not provide much perspective on his art. Therefore I have chosen to analyze two of his pieces in regards to the era of political and historical context surrounding them.

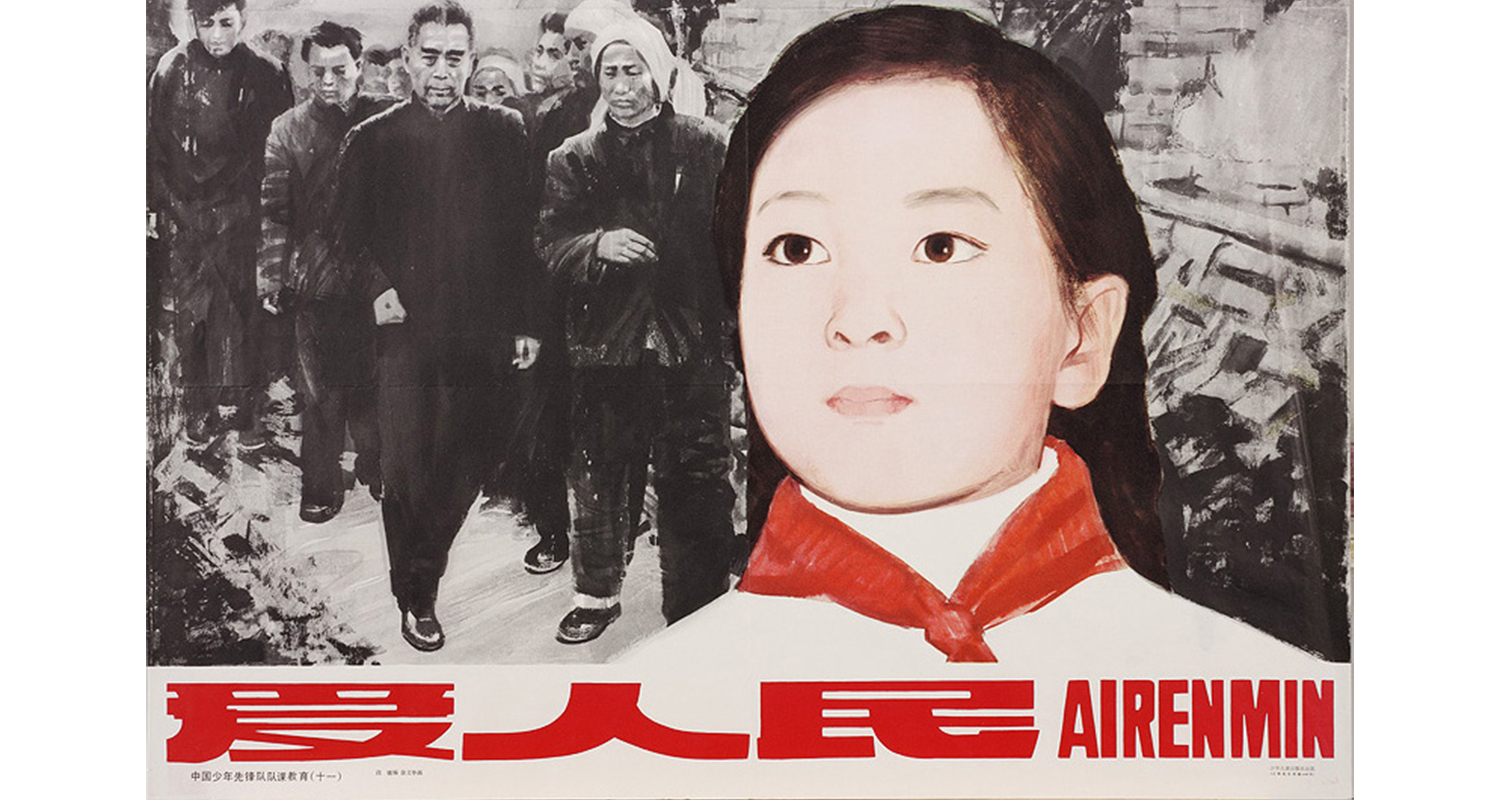

Xu’s 1976 Love Your People features a young girl – between the ages of nine to eleven – in a bright white shirt and vibrant red ascot. On the print she is placed in front of a group of older workers, who are colored in black and various shades of grey. The girl’s very pale skin and luminous attire make her pop even more so in the piece. Her expression is distant, largely unreadable and her gaze stares onwards left of the viewer, while the workers in the background appear haggard and soured. In bright red lettering at the bottom of the piece are the words “love your people” in Chinese characters.

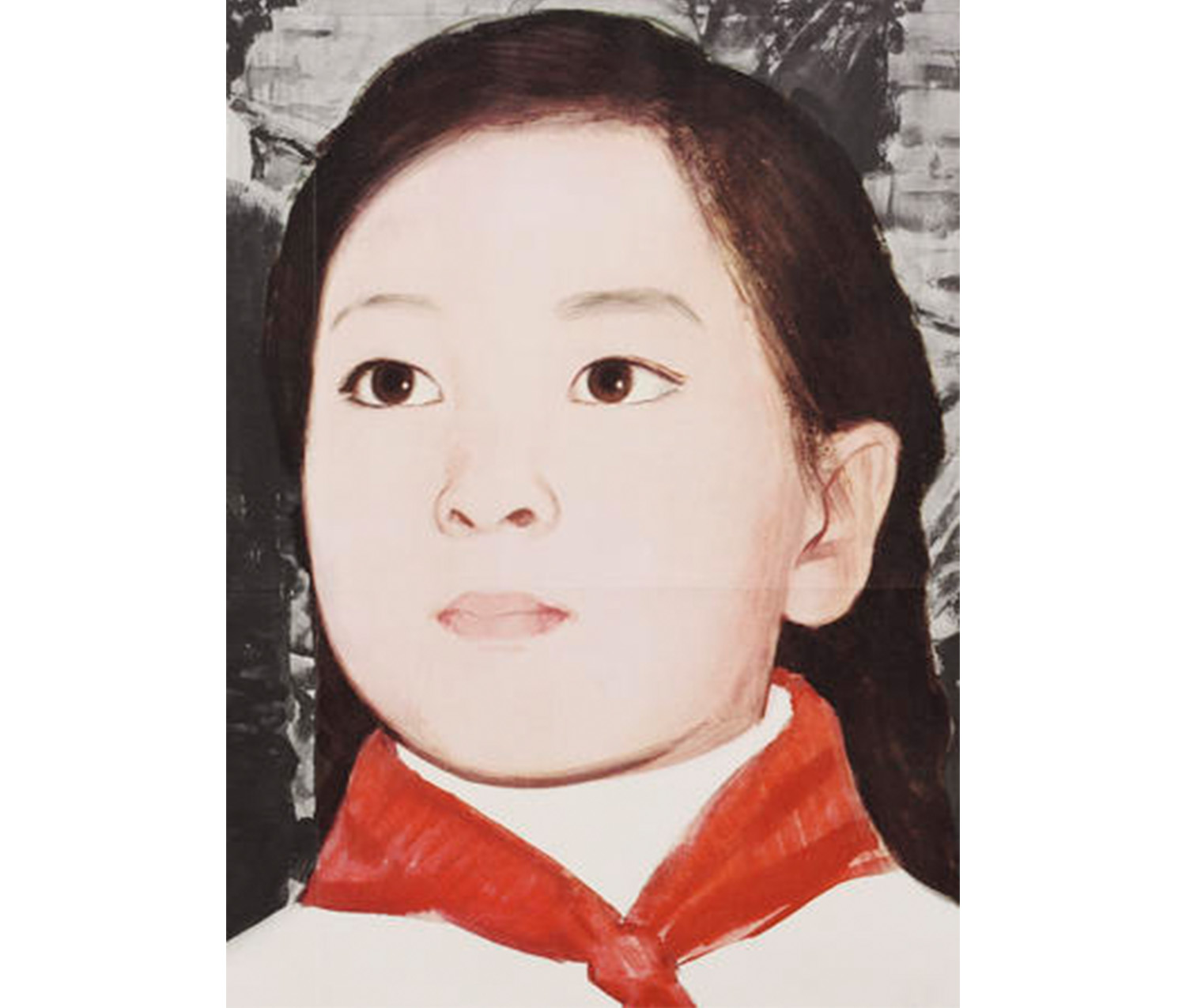

Detail of Love Your People

Overall, the image evokes a dismal solemnness which does not fit the warm expression underneath it. Its detail is rather simple, whereas Xu’s 1980 Study Hard, Prepare for the Progress of the Socialist State is an explosion of pattern and color.

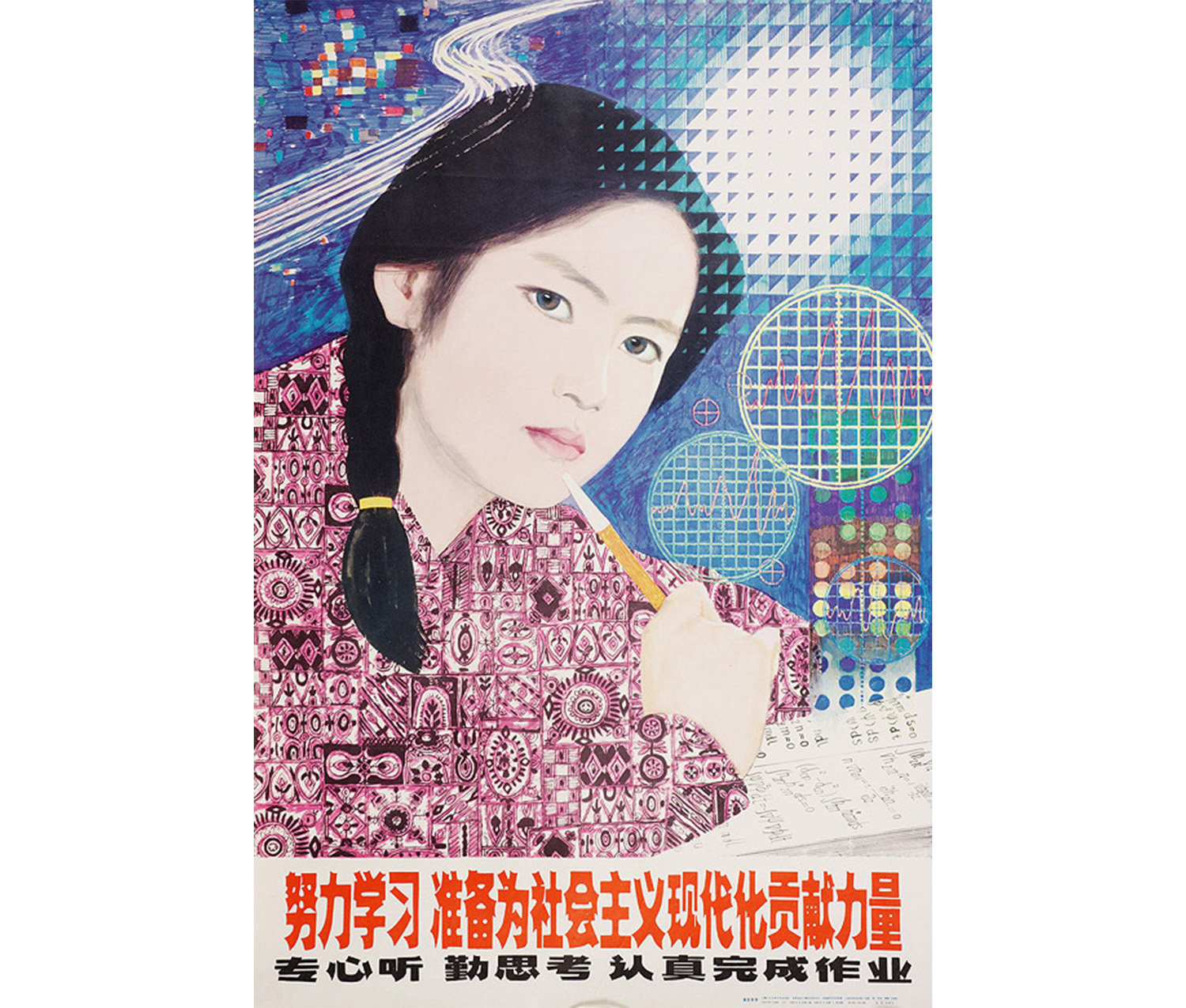

Xu Wenhua. Chinese, born 1941. Study Hard, Prepare for the Progress of the Socialist State, 1980. Four-color photomechanical print on paper. Gift of Andrew Kim and Wan Kyun Rha Kim, class of 1960. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2004.40.3.

This print features another young girl – this time between ages fourteen to sixteen – who sits at a desk looking at the viewer through her peripheral vision. The background is extremely bright, showcasing many blues and other contemporary pop colors. Behind her head is a group of colors in a square pattern, above her head an arrangement of radiant white triangles which fade into green and lastly, to the right of her face, are circles containing mathematical graphs. Her outfit has checker boxes, each filled with a different type of pattern, however all in the same shades of pink and maroon. Her expression seems cold, unfriendly, thoughtful yet uninterested in whatever currently holds her gaze. The slogan at the bottom yet again reads the title of the work in Chinese characters.

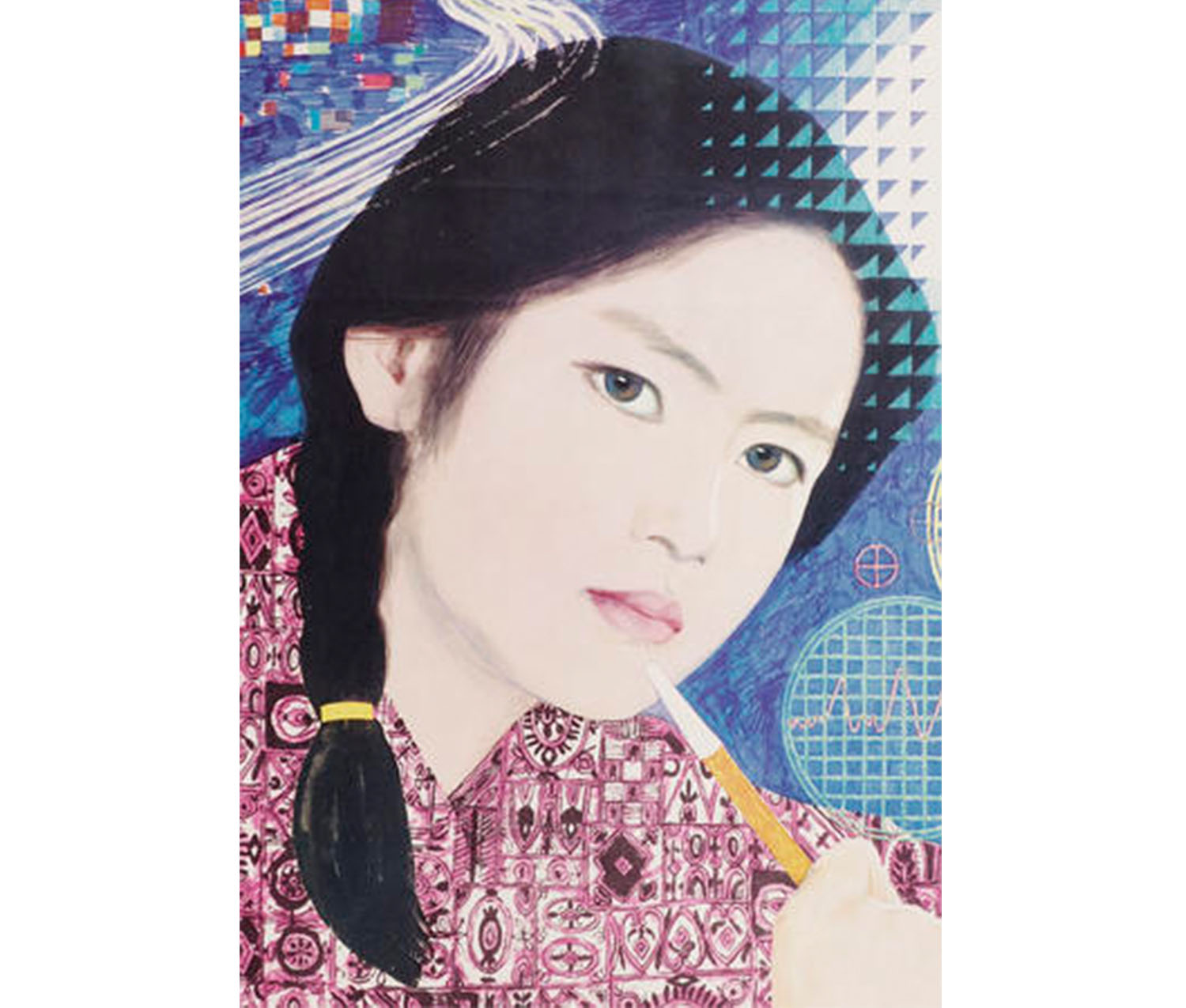

Detail of Study Hard, Prepare for the Progress of the Socialist State

The prints themselves are striking, but become more profound in regarding the country’s historical and political background at that time. The dates of their creation indicate they were made right after China’s Cultural Revolution, which took place from 1966 to 1976. The revolution was a time of great upheaval, chaos and destruction. Mao Ze Dong, China’s leader at the time, ordered the demolition of anything pertaining to the Four Olds – old culture, customs, habits and ideas.

Although the idea was to fully recreate China, the motive of the revolution was more so a strategy to secure Mao’s political position and rid him of any opponents. Mao ordered an attack on scholars, upper- class citizens and anyone else of high education or with the ability to receive one. Essentially, anyone whose opinion could potentially threaten his teachings. Homes were searched, public persecutions and humiliations took place, and families were broken up. Parents deemed class enemies, rightists or counterrevolutionaries were sent to the countryside for re-education while their children remained at home in the city.

With this enforcement of lifestyle restrictions and destruction of past culture, art was undoubtedly constrained as well. Artists were only allowed to paint if their work supported the revolution or advertised communism. Hence the birth of Cultural Revolution propaganda posters – often images of Mao or groups of happy citizens carrying red books. This period of immense tyranny did not end until Mao Ze Dong’s death in 1976. After which a time of relaxation – in terms of censoring policies – stemming from the late 1970s to early 1980s followed as the government tried to regroup themselves. Thus in understanding this context, after a time of being forced to draw in a very specific and strict genre, why would Xu create works so similar to posters of the revolution?

At first glance, while Xu’s work may seem a reiteration of the posters, there are many notable differences which infer a different perspective. In traditional propaganda posters, a common motif was use of the color red – some element of a work if not many were in this color. The people featured in the posters are often smiling or looking courageously determined as if ready for hard work and the fight for China’s new era. Most often posters showed citizens carrying little red books, doing farm work, marching, or Chinese youth gathered together wearing Mao’s attire – all of which emphasized harmony and agricultural labor. These posters were in bright colors, and illustrated massive crowds or smaller large groups. Likewise, if a poster did feature a single person, Mao was predominantly the main character.

Yet while Xu’s prints do have a revolutionary slogan at the bottom, and showcase Chinese youth, the girls in his work are not smiling. In Love Your People, the background workers look neither determined, happy nor energized. They appear in shades of grey, a stark contrast to the colorful revolution posters. For while some posters were featured in black and white, the color grey remained absent and a red component was still incorporated – either as the background or an article of clothing. Furthermore, there is not a trace of tenderness or warmth in the girl’s face negating the work’s title Love Your People. Thus the work seems to make fun of the idea by juxtaposing the workers and young girl with this statement, highlighting the phrase’s superficiality and detraction from the real concerns at hand.

The drawing style of the first painting correlates with the revolutionary posters, while the second 1980 print copies the tradition of bright color. However, the predominant color is mostly blue, not a trace of red appears in the entire work. The background is very abstract, only the girl and her study book are drawn realistically - which also differs immensely from the style utilized by propaganda posters. The girl student’s clothing – full of patterns – becomes very distracting, completely the opposite of clothing worn by Chinese youth in the posters. In the background, so much goes on around her, making it hard for the viewer to focus on her alone – despite the fact she takes up most of the center of the painting. With so much confusing, surrounding movement, it begs the question, how can she possibly study hard? The title proclaims “progress the state” but most posters with motivational messages showed people smiling, as if to claim they are happy to work for their country. Whereas the girl looks cold and uninterested. Another curious aspect is that her study book features math. Whereas the only educational books featured in propaganda posters were mainly Mao’s Little Red Book. Universities and other institutions of higher education were completely shut down during the Cultural Revolution, which makes the piece all the more ironic.

Among Chinese literature, art, and essays there is a common theme of double entendre. In the past due to Emperor’s decrees and in the present to censorship and government restrictions, anything featuring a strongly adverse opinion or critique had to be hidden. Thus all works usually have a second, or perhaps multiple underlying meanings. Though Xu’s work may appear to be similar in function to the posters, the subtle differences tell another story. In Julia Andrew’s Post-Mao Dreaming, she mentions Zhang Hongtu, another Post-Mao era artist, stated his Mao series feels like “a cathartic purging of his early artistic and ideological education.” Therefore Xu’s prints could be interpreted as an intentional mockery of Mao’s doctrines. Love Your People, a statement on the hardship the time period caused while the abstract background of Study Hard is a mirroring of the political scramble afterwards.