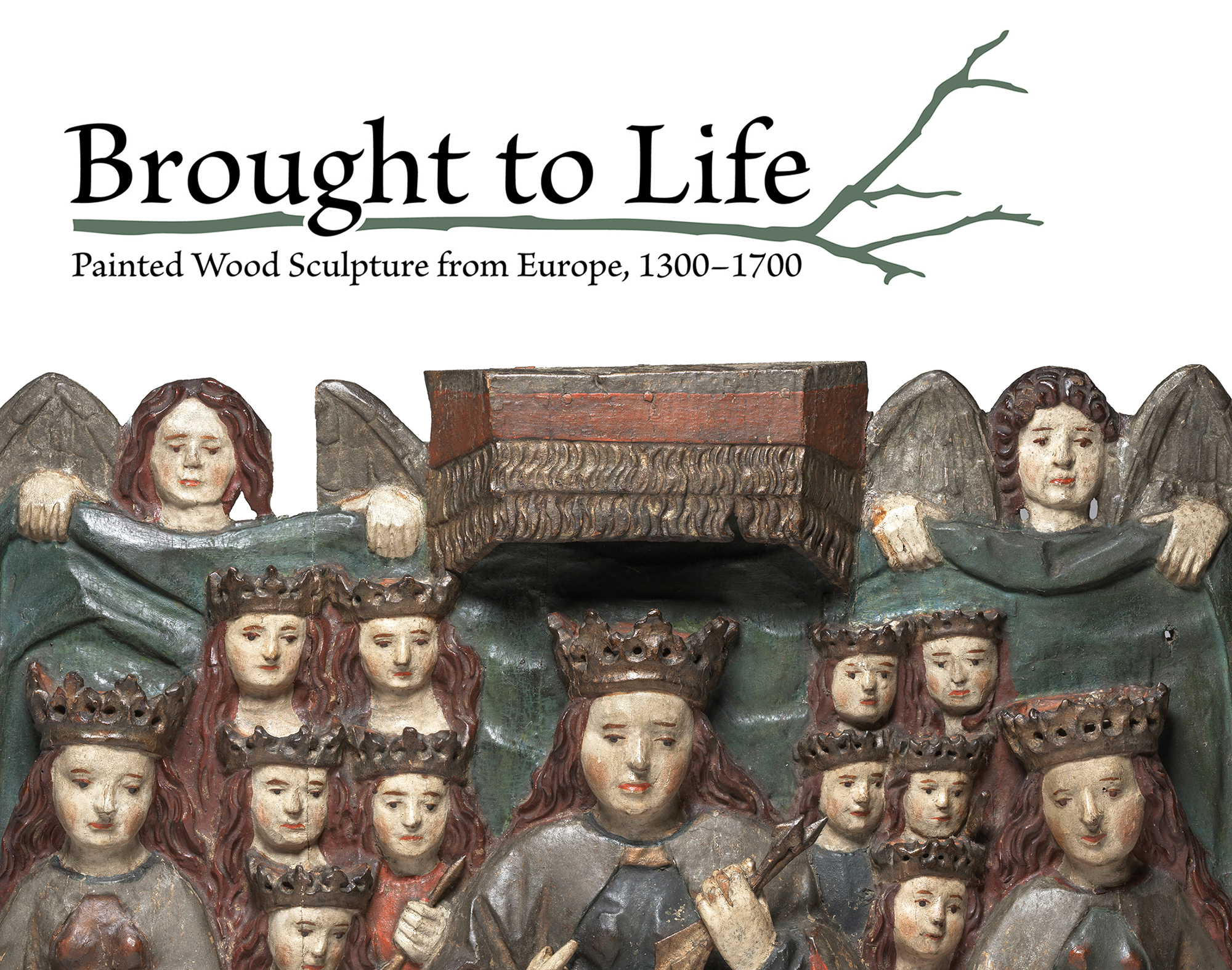

Brought to Life: Painted Wood Sculpture from Europe, 1300–1700

This exhibition investigates the materials, techniques and reception of painted wood sculpture in Europe between the 13th and the 18th centuries. Polychrome (multicolored) wood sculptures are today recognized as art objects, but at the time they were made, viewers interacted with the sculptures as if they were alive. Most of the works on view here represent sacred figures from Christianity, and their lifelike appearance was central to their function as objects of prayer and devotion. Whether located in a church or a home, the sculptures were part of a multisensory experience. They were often dimly lit by candlelight. Worshippers would have touched, held or kissed them. The air around them may have been filled with the sounds of music and the fragrance of incense. The exhibition aims to recreate elements of this original viewing experience.

To make these objects, teams of specialized artists in workshops collaborated to intricately carve blocks of wood and add paint and gilding (gold decoration). Limewood, walnut and oak were primarily used, which were readily available and relatively easy to carve. Wood also had religious meaning, symbolizing humility and regeneration. Many carvings were part of larger, more complex ensembles. Today, sections of the original sculptures are often damaged or lost, but conservation technology allows us to learn about how they were crafted and may have once appeared.

Explore the exhibition with this virtual tour!

Use the arrows to move through the gallery or drag the image to rotate your view.

This online tour was created by Smith College's Interactive Media Coordinator Andrew Maurer.

Most of the sculptures in the exhibition feature saints. According to the Christian faith, saints are people who lived extraordinary lives in the service of God. Many saints were martyred (killed for their beliefs). The miracles they performed in life or after death secured a spot for them in heaven. Their main role is to act as mediators between God and the faithful by communicating and directing their prayers.

Saints are frequently associated with specific misfortunes or difficult aspects of life. For example, people could pray to Saint Roch if they were suffering from plague or to Saint Anne for assistance in childbirth. The holy figures are often shown holding objects that refer to their martyrdom, miracles or other aspects of their life. These attributes made them immediately recognizable to viewers.

Originally, viewers experienced these sculptures in environments that evoked multiple sensory responses. To simulate this experience, the gallery is dimly lit. Visitors are invited to handle a painted 3D scan of the Saint Fiacre sculpture, to feel its weight and trace its crevices. Music composed by Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), dedicated to Saint Ursula and sung by the Smith College Chamber Singers, plays above the sculpture of Saint Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs.

Unknown German workshop. Saint Roch, 15th century. Polychrome and gilding on wood. Gift of Jane T. N. Fogg, Class of 1954

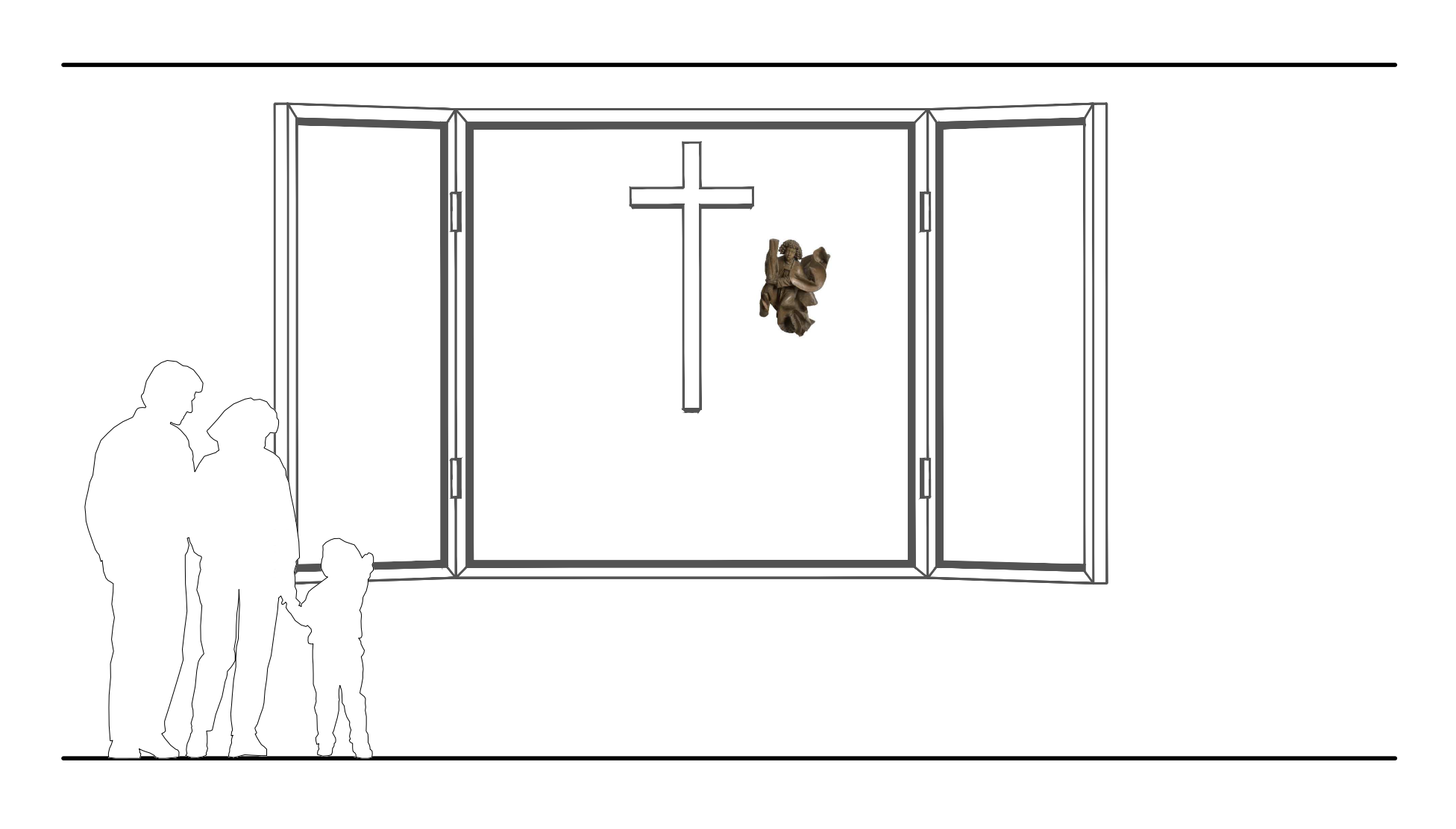

Many surviving painted wood sculptures were once part of larger altarpieces. Protective side panels were attached with hinges to the central portion, which featured sculptures. These painted panels, or “wings,” would be opened only for holidays and important rituals. Altarpieces of this type usually included a superstructure at the top and a predella (base) at the bottom. Their various sizes, shapes and styles were determined by local trends, funds and time periods.

Few intact altarpieces with painted wood have survived. Many were destroyed during the Reformation, when religious imagery was no longer permitted. Others were neglected or sold off in parts. There is no record of the original altarpieces into which many of the sculptures in the exhibition were once integrated.

Andrew Maurer of Smith’s Imaging Center and Exhibition Designer Justin Lee, in consultation with the exhibition’s curator, created a scaled schematic graphic of an altarpiece based on surviving examples.

The exhibition pairs two sculptures—a Lamentation (a word meaning the expression of sorrow) and a Pietà (an Italian word with Latin roots meaning pity)—since they show how different cultures and time periods represented similar subject matter. Both display the emotional outpouring of grief associated with the moment after the dead Christ has been lowered from the cross. While the Lamentation involves a larger group of mourners, the Pietà focuses on Mary—Christ’s mother—holding her dead son in her lap, overcome with sorrow. Neither of these events is recorded in religious scripture, but they became popular subjects in art.

The Lamentation may have been part of a larger altarpiece typical in German churches at this time. Lamentation scenes were often placed beneath Crucifixions as the next event in the story. The figures around Christ’s dead body look out in various directions as a strategy to capture viewers’ attention within the vast architectural space of the church. The Spanish Pietà, by contrast, was created for a more intimate setting, as seen in the intricate decoration and shallow carving.

Unknown Spanish workshop. Pietà with Saint John and Mary Magdalene, mid-16th century. Wood with paint and gilding. Purchased. AC 1988.1 Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

Not all painted wood sculpture had a strictly religious function. The two works in this section are both idealized, but they do not represent recognizable holy figures. Like their religious counterparts, they were crafted in specialized workshops using the same materials and techniques. By the time of their creation, most people understood painted wood statues as “living” presences. Their poses and facial expressions encourage viewers to interact with them but in a less direct and personal way than religious sculptures. These secular sculptures also would have had more specific viewers in mind, such as people of a certain social or political rank, according to where they were located.

Although we do not know much about these two sculptures, they offer clues as to their original settings. The Falconer, decorated on all sides, may have been part of a larger scene or stood alone. His dress associates him with court culture, which was open to only a select few. Meanwhile, the Allegory of Modesty (on loan from the Yale University Art Gallery) may have been placed in a more public space, probably against a wall. Only an educated viewer would have been able to understand its symbolic references.

Unknown workshop, French? Falconer, 15th century? Oak with paint and gilding. Purchased with the Drayton Hillyer Fund

At the end of the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation transformed the use and appearance of visual art. Martin Luther (1483–1546), a German monk and author, began this spiritual revolution by publicly expressing his dissatisfaction with the Catholic Church and its leader, the pope. In response to these complaints, the Catholic Church underwent its own series of reforms known as the Catholic or Counter Reformation.

One of Luther’s disagreements with the Church involved its use of art. He cited a centuries-old argument that the faithful risk worshiping idols rather than the holy figures represented in painting and sculpture. Concluding that art is not necessary to commune with God, Protestants did away with figural religious imagery. Much existing art was either destroyed or neglected. The Catholic Church responded by placing even greater importance on art’s role in the faith.

By the 17th century, areas of Europe that remained predominantly Catholic, including Spain, produced painted wood sculpture in greater numbers and on a grander scale. Rules about how it should look and its proper use were codified and enforced by the Church. The two examples in the exhibition show the extreme naturalism and new emotional charge found in Spanish sculptures from this time.

Unknown Spanish workshop. Saint from a Reformed Order, early 18th century. Wood with paint, gilding and glass. Purchased. AC 1956.81 Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

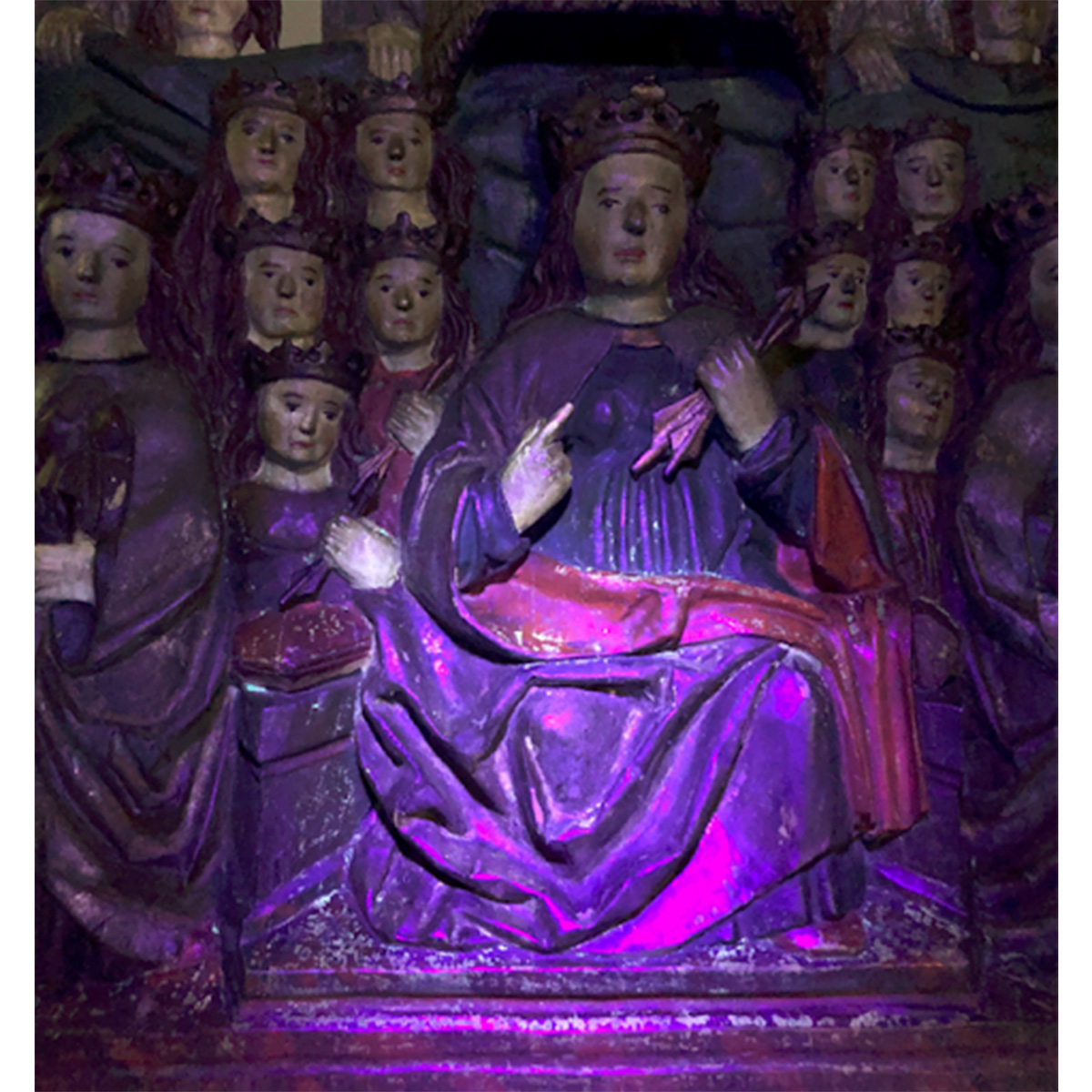

Art conservation plays an important role in the care and preservation of works of art. Objects conservator Valentine Talland treated four sculptures in the exhibition. Each sculpture was cleaned and assessed for its level of damage, loss and overpainting. Close examination reveals how these sculptures were constructed, either as single pieces of wood or as multiple joined parts. Ultraviolet (UV) light also provides information about previous paint layers and restoration efforts.

The sculptures were also examined with an X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer to determine the elements present in the wood. The results were then compared to elements present in pigments in order to understand what colors lay beneath the painted surface. These techniques are especially helpful for studying painted wood sculptures because they were commonly repainted according to changes in taste or as a now outdated form of “restoration.” While conservators typically remove material that is not original to the work of art, the many layers of paint on these sculptures are left intact because they are an important part of the objects' histories and functions.

An in-gallery video offers more information about the conservation of the four sculptures, including the results of the XRF analysis. This video is also available on the website under the red Watch button above.

Unknown German workshop. Saint Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs (under long-wave ultraviolet light), 17th century. Limewood with paint and gilding. Gift of Frank A. Newlin in memory of his mother, Mrs. Isaac Chapman Bates. Photograph by Valentine Talland

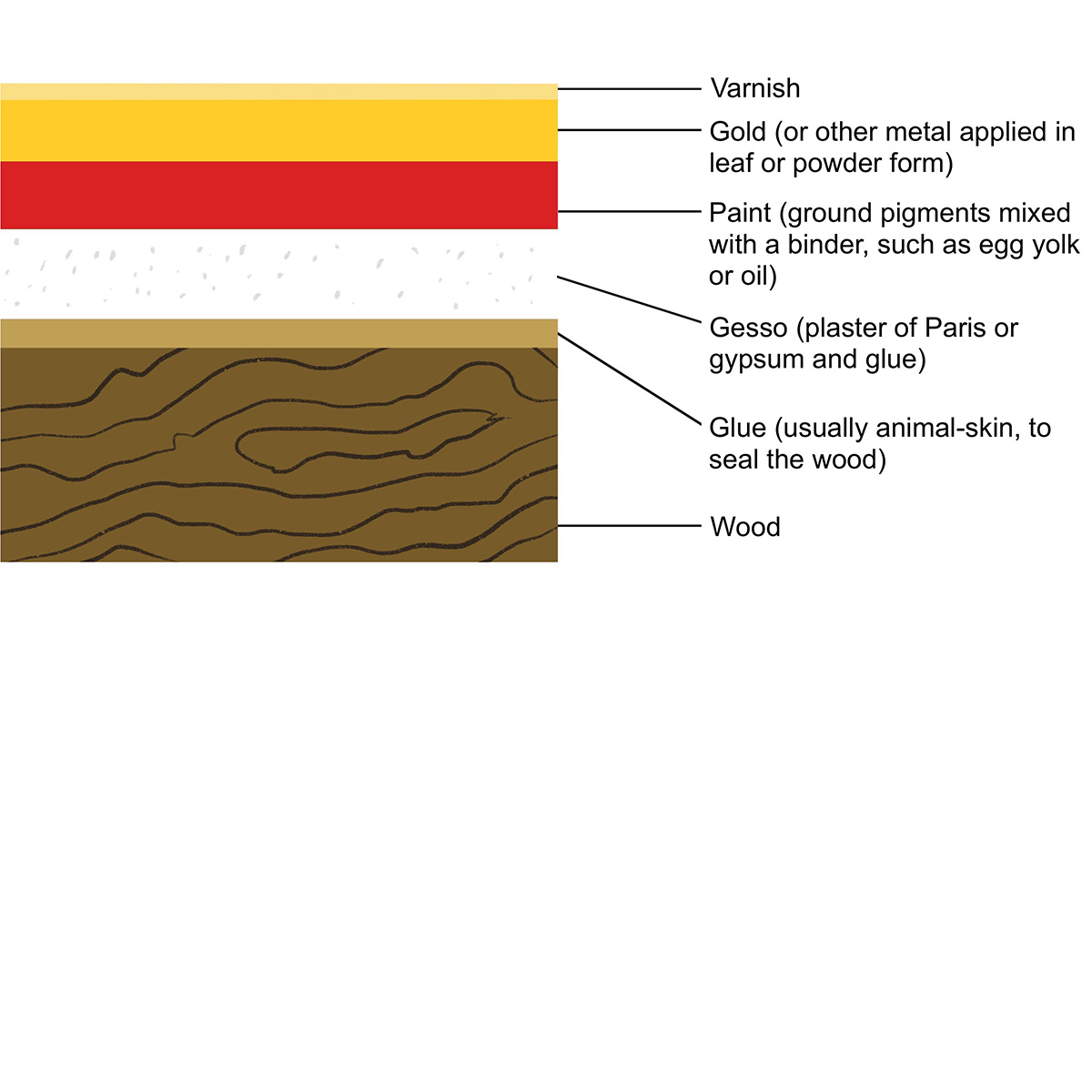

The production of painted wood sculpture was a collaborative effort that involved a variety of artistic techniques. Sculptors used gouges and chisels to hollow the wood and remove material. Then, a layer of gesso (plaster of Paris or gypsum mixed with glue) was applied to create a smooth surface for painting and gilding. In preparation of painting, assistants ground pigments derived from plants and minerals into a fine powder and mixed them with a binder, such as egg yolk or oil. Gilders applied gold and silver in leaf or powder form, either before or after the application of paint, depending on the desired effect. These are only some of the roles and techniques involved in the process. The exhibition contains a case containing tools and materials similar to those the artists used to create painted wood sculptures.

Artists’ workshop often did not determine many of a sculpture’s key aspects. The patron (who ordered and paid for the sculpture or altarpiece) usually decided on its size and subject. Surviving contracts record other specifications, such as the amount of gold or types of pigments to be used. Although artists worked within these parameters, each workshop possessed its own style.

Credit: Annalise Edwards '23J

Painted wood sculptures are not usually associated with individual artists. Workshops, often overseen by a master artist, collaborated to produce painted wood sculptures that were part of multifigured altarpieces. Painters, sculptors and gilders are only a few of the specialized artists who were part of workshops, each responsible for one aspect of production.

While some names of workshop artists are recorded in surviving documents, this is not the case for any of the works in the exhibition. There are several reasons for anonymity. Until about the 15th century, artists were regarded as skilled laborers and did not usually sign their names. Our lack of information also has to do with the separation of these objects from their original contexts. Additionally, there was often no need for well-known artists to sign their works because their distinctive style was recognizable to local audiences. Continued research may someday reveal the names of the artists on view here, as well as other information about these sculptures. Until then, we must rely on visual and technical examination to determine their dates and places of origin.

Jan Collaert I, Netherlandish, ca. 1530–1581 (after Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus; Netherlandish, 1523–1605). The Invention of Oil Painting, plate 14 of New Inventions of Modern Times [Nova Reperta] ca. 1600. Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.95.870(5)

The exhibition is supported by the Suzannah J. Fabing Programs Fund.

Thank you to the students who participated in various aspects of this exhibition: Annalise Edwards ‘23J, Rui He ’25, and Cecily Hughes, ‘22 UMass M.A.

Special thanks to Principal Justin Lee at LEE²DESIGN | JUSTIN LEE ARCHITECTURE + DESIGN LLC