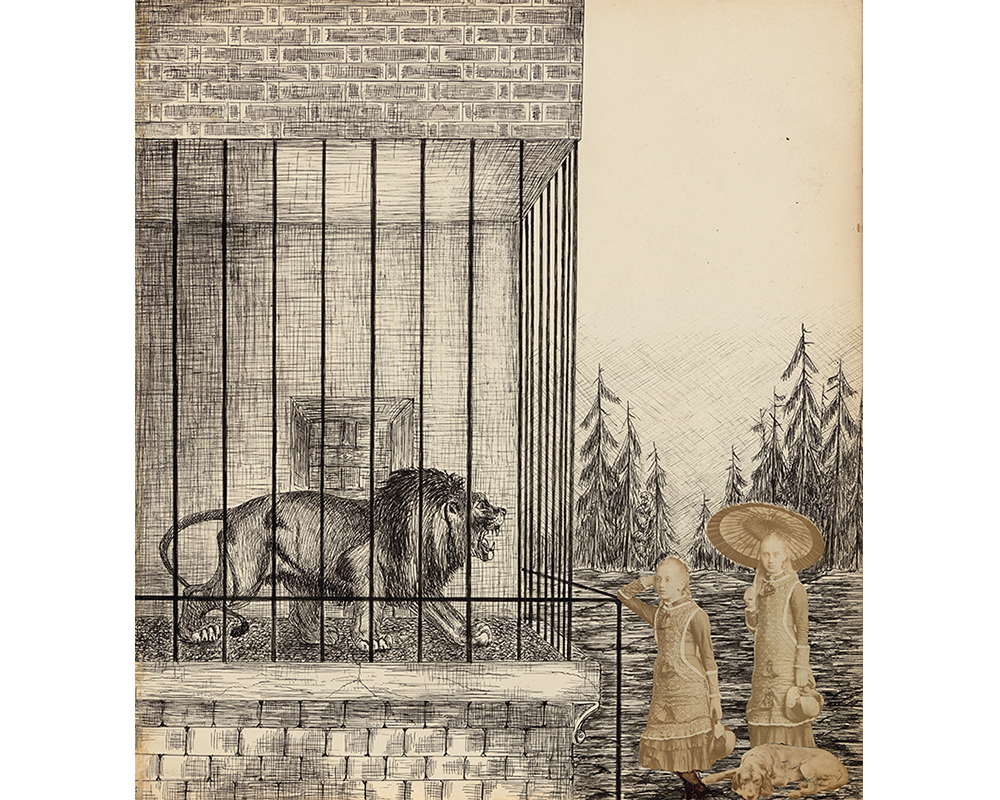

A History of Handwork | At The Lion's Cage

Guest blogger Emma Crumbley '19 wrote this post as part of her coursework for ARH 280: Photography and the Politics of Invisibility taught by Post-Doctoral Fellow Anna Lee. This course informed the current exhibition A History of Handwork: Photographs from the SCMA Collection on view on the Museum’s second floor until December 3, 2017.

At the Lion's Cage was made in England in the 1870s, when photocollage was at the height of its popularity. The anonymous artist, only known as “J.F.,” was most likely an upper class British woman Victorian photocollage was almost exclusively made by upper class and aristocratic British women, and was intended to be circulated among a close circle of friends and family, so it makes sense that J.F. did not sign her whole name. Although this image seems simple at first--an amateur drawing of a lion in a cage next to cut out photographs of two bored looking girls-- J.F. has used symbolic elements of Victorian culture to infuse it with meaning. J.F. would have cut the photographs of the girls out of a portrait in order to place them into her drawing of the zoo. Her decision to create a photocollage set in the zoo is reflective of the high society in which she likely lived. Not only an important arena for aristocratic socializing, the zoo itself was a monument to the way in which humans were able to dominate over even the fiercest of wild animals, reflecting the imperialist attitudes from which the British aristocracy benefited. In At the Lion’s Cage, the young girls’ blasé response to the lion roaring at them could be a reflection of the distance that visitors in Victorian zoos felt from the animals in captivity, which itself could be seen as reminiscent, whether or not J.F. wished it to be, of the distance between the aristocracy and the people who were oppressed by Britain’s imperialism.

J.F.’s decision to place these girls next to the lion is also perhaps a reflection on her own oppression as a woman in Victorian England. At this time, cats were frequently pictured alongside women and girls, and used as a warning to women who desired to be free of the confines of domesticity; they were wild creatures who lived at the whim of their untamed sexuality and innate immorality. The inclusion of the lion, then, as the biggest, strongest cat of all being kept in a miserable, tiny cage, is symbolic of the faults that J.F. found in these sexist claims. Alongside the lion, the two young girls, standing with open land spread out behind them, represent a freedom that most aristocratic Victorian women only felt in childhood--before they married, had children, and were burdened with the labor of domesticity and social fluency. Perhaps within this direct contrast between the freedom of youth and the captivity of adult womanhood, with the aristocratic zoo as a backdrop, is a statement which J.F., was able to hint at in this seemingly simple image.