(after Carel Fabritius, 1654)

A J-term Class about Painted Wood

In a recent J-term course inspired by a forthcoming exhibition at SCMA, Smith students learned about historic painted wood sculpture and tried their hand at painting on wood using traditional materials and techniques. Danielle Carrabino, curator of painting and sculpture, shares her experience teaching this class.

What’s so great about painted wood sculpture? That was one of the questions that prompted students to enroll in “Studies in Museums: Painted Wood Sculpture” (MUX 222) this past J-term. For one intense week, fifteen students from a variety of majors and class years examined European painted wood sculptures from the 14th to 17th centuries. The class focused on four works from the SCMA collection. These and other sculptures will be on display in the forthcoming exhibition at SCMA, “Brought to Life: Painted Wood in Europe, 1300-1700.” For their final assignment, student groups wrote a wall label, which may be featured in the exhibition. As the curator of “Brought to Life,” I wanted to explore with students the history of these sculptures, including their intended function and context, how they were made, and why they’re so great.

Among the topics we discussed in the class was “why wood?” and “why paint?” What were the ideas behind selecting these materials for sculptures that often had the function to aid in prayer? In order to communicate with the viewer, these sculptures were viewed as seeming alive. Wood was often selected for because it was itself once living. Once it was carved and decorated with paint and gold, these sculptures had a lifelike quality. However, today many of them have suffered from age, usage, and neglect so their original appearance has been lost. Many of them now have only traces of their surface decoration, were heavily repainted, and show the marks of wood-boring insects. Some also show signs of wear due to being handled or kissed. Candle smoke and dust has also obscured whatever color remains so that they are a shadow of their former selves.

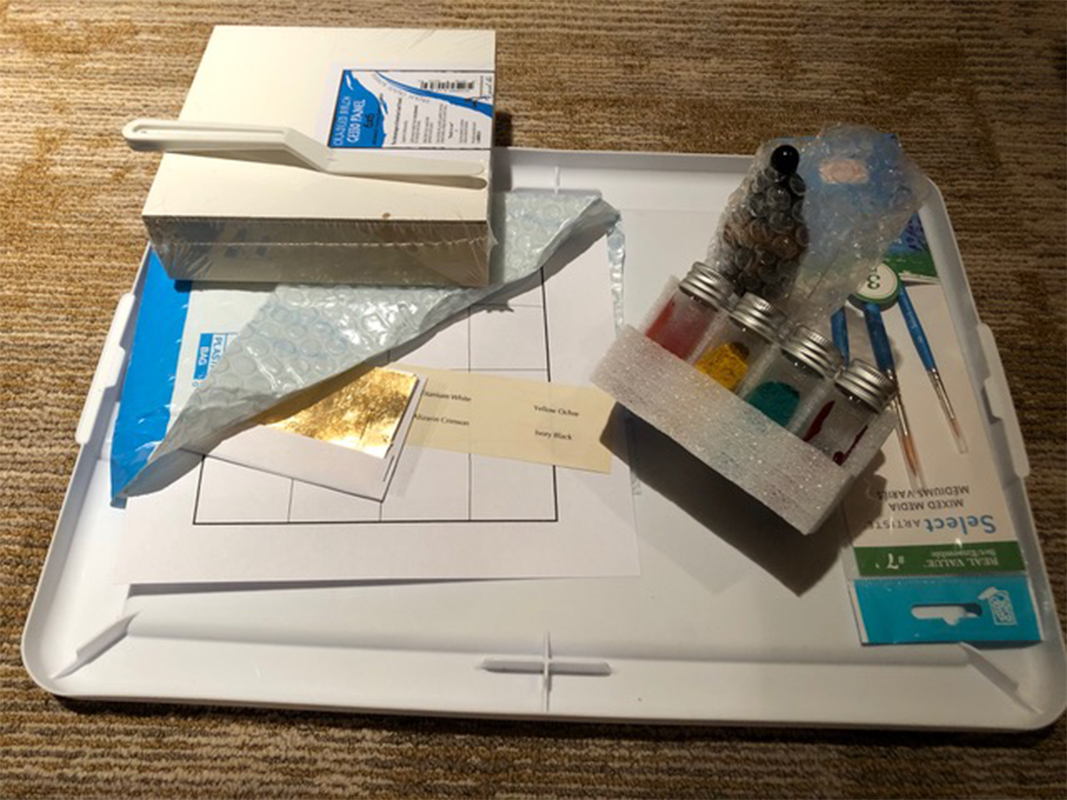

A key theme in both the course and the exhibition is the important role of conservation. The removal of old varnishes and dirt from the surface allows us to look even deeper, beneath the layers of paint, to learn about their original appearance. Objects conservator Valentine Talland enriched the course by sharing what she had discovered about these sculptures in her recent analysis and conservation of them. She introduced students to art conservation and shared her experience of working with painted wood sculptures over the course of her career. She also provided a hands-on workshop that guided students in creating a painted wood panel. Each student was provided with a box of art supplies to create their own paintings using many of the same traditional materials and techniques used to create the sculptures we were studying.

The theme of wood as a living material is another aspect of the exhibition we explored in class. John Berryhill, Landscape Curator at the Botanic Garden taught us wood in its original form: trees. He presented to the class about the amazing world of trees, including three species that provided the wood for some of the sculptures in the exhibition (limewood, oak, and walnut). He also opened our eyes to the many glorious trees that surround us on the College’s campus, an accredited arboretum.

Students came away with an appreciation for the sculptures, art conservation, and how exhibitions are realized. Chi Qiu ‘24 summed it up by saying, “The course provides me with a new perspective that I cannot see from merely visiting the museum. There’s a tremendous amount of work behind the exhibitions, which gives another layer of meaning to the exhibits from contemporary people.” Some even expressed an interest in pursuing careers in conservation, museums, and art.

Though first conceived as an in-person class, it was offered remotely in keeping with the College’s recommendations. While the students were not able to experience the joy of examining works of art in person, there were some benefits to learning remotely. Though extremely difficult, the meditative nature of painting on panel provided a welcome opportunity for the class to turn off their cameras and become immersed in their projects. Later this month, the students from the class are invited to the museum’s storage space to view the sculptures they studied in person.