Printmaker Barry Moser on Bringing Frankenstein to Life

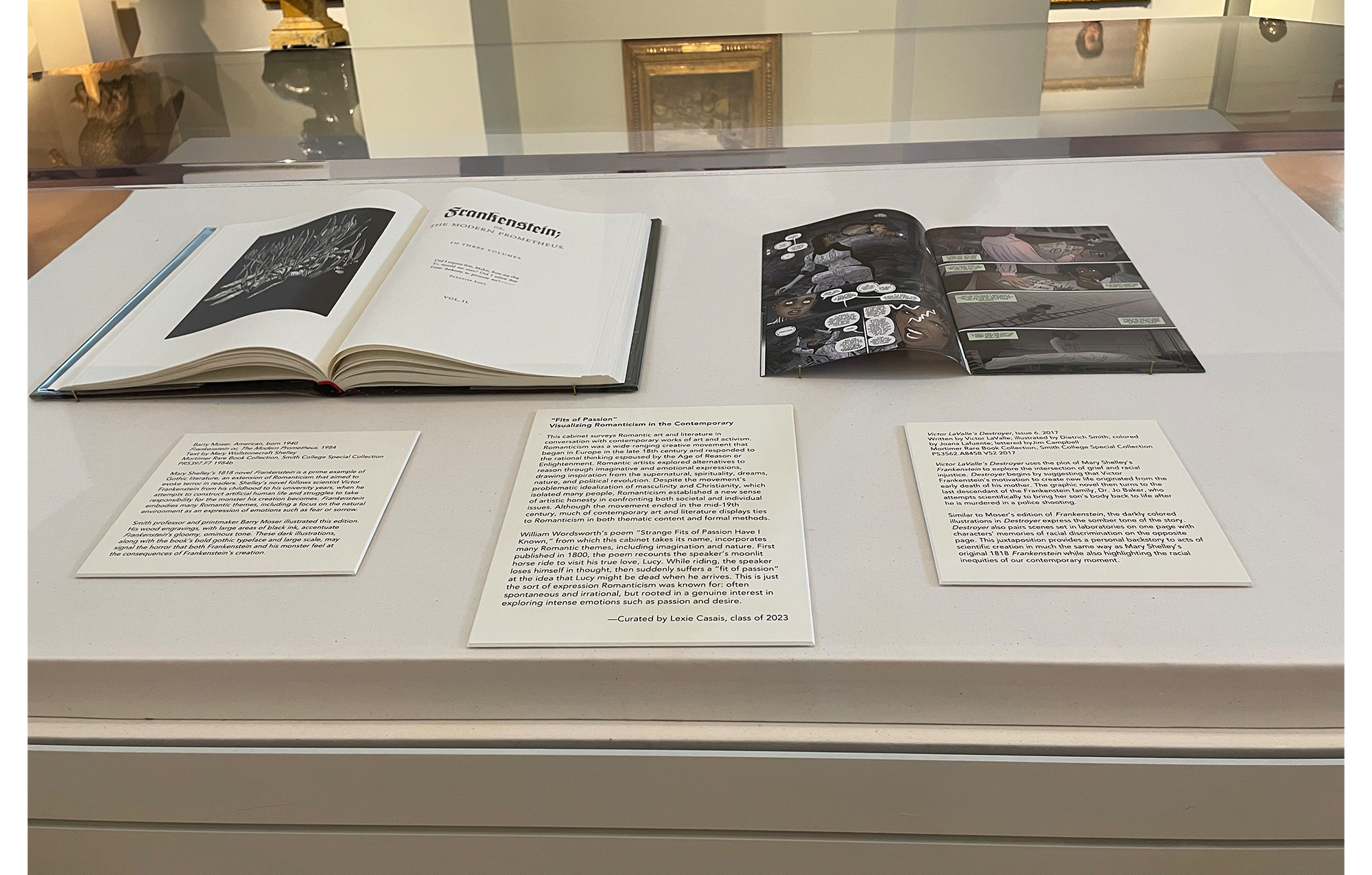

Indigo Casais ’23 is an art history and English double major and a student assistant in the Cunningham Center this summer. Indigo is the curator of a cabinet titled 'Fits of Passion': Visualizing Romanticism in the Contemporary, which pairs Romantic and contemporary artworks. The cabinet is on view on SCMA's third floor.

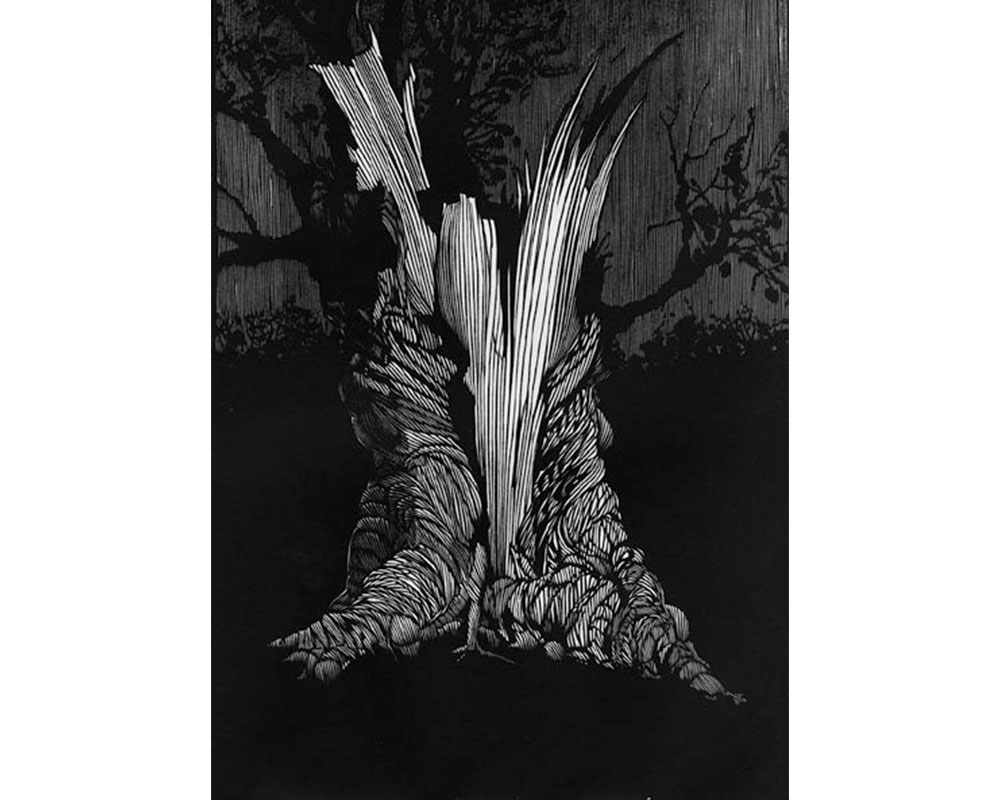

In addition to being a Smith College professor, Barry Moser is a printmaker and illustrator of numerous works of literature including the King James Bible and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. His illustrated edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is displayed in the Fits of Passion cabinet.

Romanticism was a wide-ranging artistic and literary movement that explored alternatives to reason. Romantic poets and artists drew inspiration from subjects such as the supernatural, spirituality, dreams, nature, and political revolution. In this interview from March 2020, Moser and I discuss how these themes appear in Frankenstein. We also discuss the motivations behind his illustrated edition of the book, the impact of place and nature on his work, and the process of reinterpreting a story and giving it visuals.

What are the things that you find most important about the story of Frankenstein, and about your edition of Frankenstein?

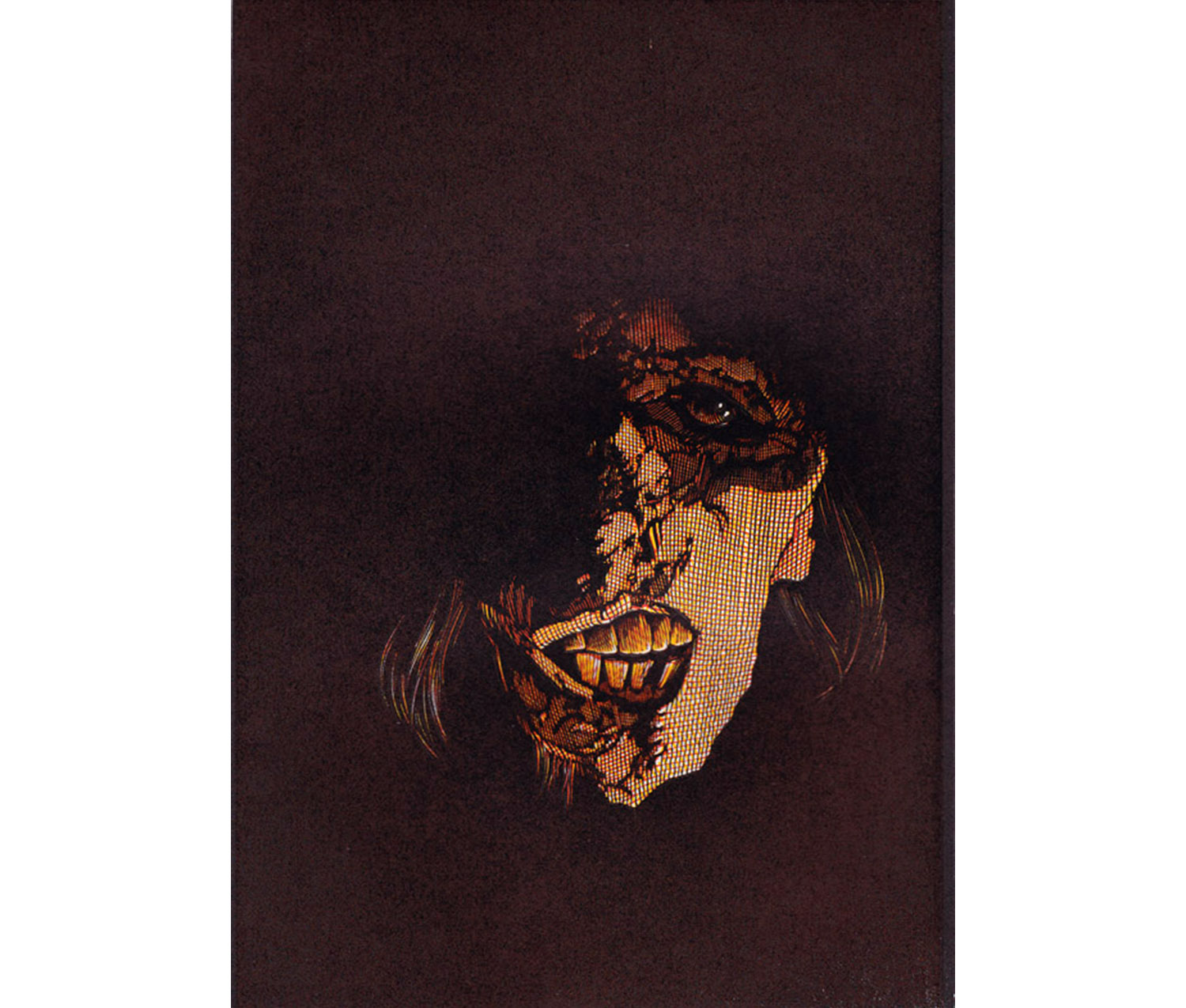

Well, the primary thing is the sympathy with the monster that is embodied in the middle section [of the book]. I don’t want to get into how I came about what the monster looks like, but it’s pretty horrendous. He is yellow. As an illustrator, there are very few things I can’t do, but one of the things that I can’t do is contradict the author. Mary Shelley says very plainly that, when she had that dream, when she woke up, she looked into his face, and it was yellow. So there’s no question about how she saw the monster’s face: yellow.

But then, my philosophy came about when I was reading the section where the monster comes up to the man and his girlfriend out on the river, and she falls in. The young guy, instead of thanking this eight-foot-tall guy for saving his girlfriend, pulls out a goddamned shotgun and shoots him. Well, I grew up in the Jim Crow South, and when I read that, the question came to mind: What would that boy have done had that been a seven-foot-tall national basketball player who was white? What would have happened? Well, I think the answer is that he would’ve thanked him. But no, in this case, he wasn’t white, he was yellow, so the guy shoots him because of what he looked like. And that bothers me.

So, what I did was, in the second through the last portrait in the series that comprises the entirety of the second body, the face becomes colorful. Not colorful as in primary colors, but as in autumnal colors, the colors you might associate with a fireplace. So those conversation portraits in the middle [of the book] go from the yellow that Shelley dictates, and through my feeling of sympathy for this character, give that character, and only that character, color. Everything else is black and white. That’s the first thing that I would hope people would notice [about the illustrated edition].

Barry Moser. American, born 1940. No Father Watched my Infant Days from Frankenstein or, the Modern Prometheus, 1983. Wood engraving on paper. Photo courtesy of artist.

Most of the books you illustrate don’t come with images in their original editions. In Frankenstein, Mary Shelley doesn’t give the reader any pictures to go along with her horrific descriptions of the monster. She leaves it to the reader’s imagination. When you’re illustrating a text, how do you decide what should be left to the imagination and what should be in your prints?

How to navigate a text is an enormous problem. It takes a bit of hubris. I mean, really, it’s a very arrogant act on my part to think that I have something new to offer readers of the King James Bible that people like Velazquez and Goya and the whole history of Western art has done with Biblical images. It really is a hugely arrogant thing to do. Now, why would I want to do it? Well, I told you about Frankenstein, and the backbone of my reasoning on Frankenstein is racism. Whereas the backbone of, let’s see, what would be the backbone of my illustrations for the Bible? Pure arrogance, I think. I mean, I’m serious, it’s pure arrogance.

The other thing I think it takes, and you’re going to laugh and think I’m joking when I say this, but I mean it sincerely. It takes a degree of ignorance, and innocence. I’ll go into something, a major text, let’s say The Scarlet Letter. I’ll read it and then I’ll make my images and design it and print it as a book. And then the critics will come at it, and they will tell me all sorts of things that I didn’t know. I think the things that I don’t know often contribute greatly to the final, to the whole thing. If I came at it as a scholar, I think I would arrive at a very different place.

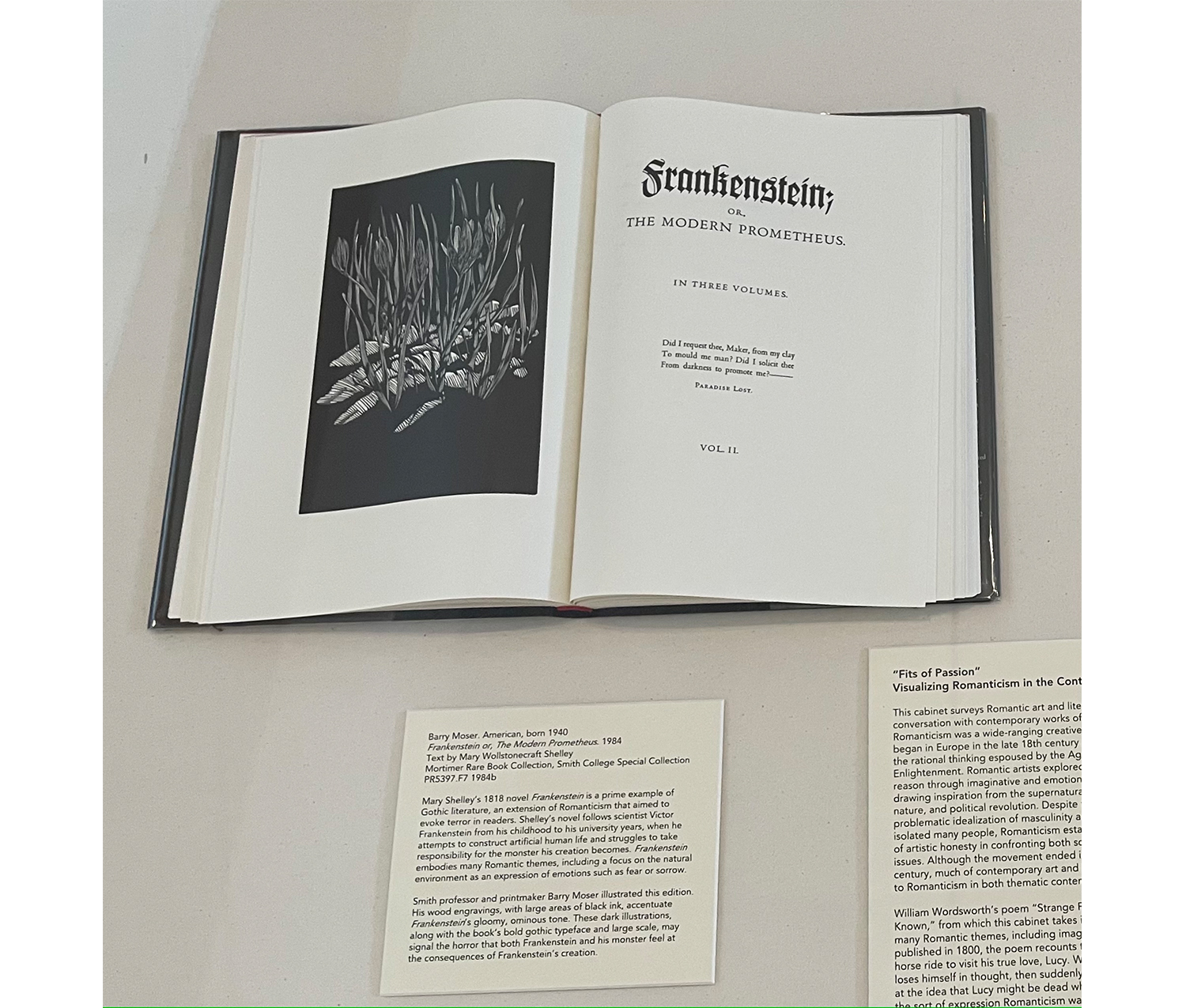

Barry Moser's illustrated edition of Frankenstein (left) on view in the Fits of Passion cabinet next to Victor LaValle's Destroyer (right)

Left: Barry Moser. American, b. 1940. Frankenstein or, The Modern Prometheus, 1984. Text by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly. Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collection. PR5397.F7 1984b.

Right: Victor LaValle’s Destroyer, Issue 6, 2017. Written by Victor LaValle; illustrated by Dietrich Smith; colored by Joana Lafuente; lettered by Jim Campbell. Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collection. PS3562.A8458 V52 2017.

An important part of Romantic art is place. These artists were impacted by physical location and by attempting to capture the emotions that these locations brought them. How does place impact your work? More specifically, how does living in Western Massachusetts impact your work?

I’m quite sure that had I remained in Dixie, I would not be doing the work I do now. Place has everything to do with it. When I arrived here, I mean, I’m on the grounds of some of the great writers and poets and artists in American history. I think that moving here and meeting someone that I admired as greatly as I did Leonard Baskin and having the ghosts of Emerson and Frost and Dickinson and all that, being around here, it gave an old ignorant Southerner like myself a kind of pedigree. It gave me a kick in the ass that I would never have gotten, I think, in Dixie. Which is NOT to say—and I would put “not” there in all caps, italic, bold—it’s not to say that the South is devoid of culture and the arts and so forth. But a culture of fine printing in the South, when I was there, was pretty much unknown. So I do think place has an awful lot to do with any artist’s work.

Close-up of Moser's illustrated edition of Frankenstein as displayed in the Fits of Passion cabinet

Romantic artists also spent a great deal of time exploring their connections to nature. Do you feel a strong connection between your work and nature or the environment, and how does that manifest itself?

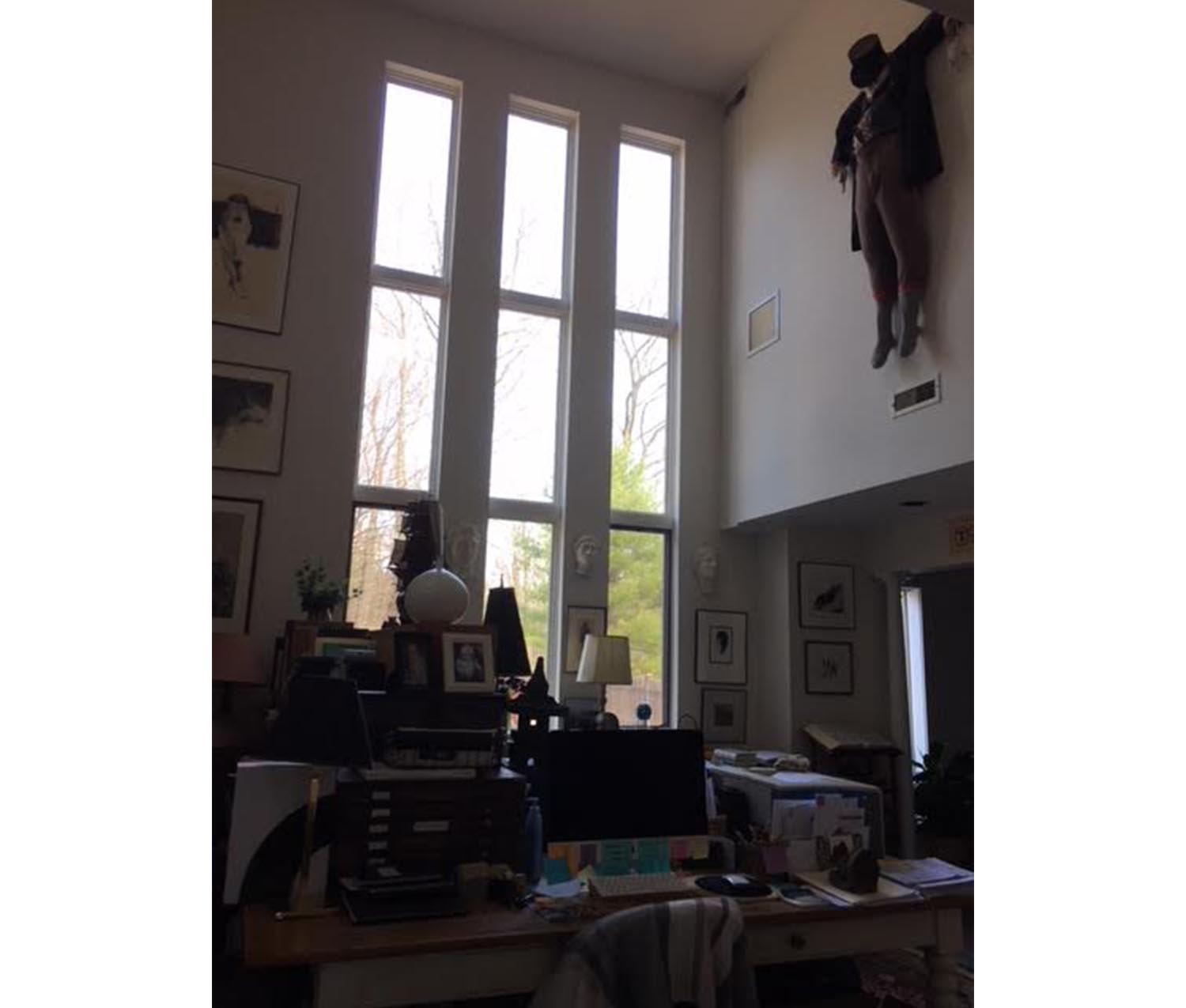

I wish I had a picture of what I’m doing at this moment. I’m sitting here at my desk, in my studio, under windows that look to the north. The windows are about twenty feet high, and there are three of them, three long slits up the side of the building. I’m looking out into the woods. It’s all I can see. I’m in the middle of hundreds of acres of woods. Nature informs my work from the very beginning—in the subject matter of my work. To me, nature, and the human figure especially, is the basis of all, or most, human expression. That’s certainly true for me.

Moser's studio. Photo courtesy of artist.

When you’re illustrating a book, how do you feel about reinterpretations of content or stories? Do you try to remain faithful to a text, or do you reinterpret, or both?

Well, as I say, I’m not going to contradict my author. If Lewis Carroll says that the Queen of Hearts wears glasses, then by god, if I do an illustration of her, I’ve gotta put glasses on that character. I don’t have a choice. I might interpret it as a pince-nez and have it hang from a pin on her blouse. There are a lot of things I can do with the glasses, but they have to be there. Now, beyond that, if Lewis Carroll does not indicate how, or if, the Queen wears a crown, I can include it or not include it. If I decide to do that, then I can do all kinds of things with that crown. I can make it comic, I can make it ridiculous, I can make it serious, I can do all sorts of things. So, in that way, I’m interpreting.

But the element of interpretation is a two-fold thing. First of all, it’s how I read a text and how I respond to it, and that response is an interpretive measure. And then when it goes away from me, into your hands, you read it, you see what I’ve done, and you may not see exactly what I intended. And therefore, you will then draw from my image your own conclusion. I think that’s a very important part of art. Once I let a book of my illustrations go, it’s out of my hands. You can interpret it any way you bloody well want to interpret it. And that does not mean that just because your interpretation of something that I did is different, that it is less valid than mine. I think that when you see an image that I’ve done and you see it in a way that I hadn’t, that’s what makes it alive. It becomes a living thing because you are giving it new life that I never intended, that I never saw.