Reproducing Reality

Julie Warchol is the 2012-2013 Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center.

Japan and Photography in the 19th-Century

When American Commodore Matthew C. Perry landed in Yokohama, Japan in 1854, the country had been in a state of isolation for over 200 years. Wary of the influences of Western civilizations, the island nation sought to preserve its culture and autonomy by shutting out the rest of the world, beginning in 1635. This era of Japanese history is known as the Edo or Tokugawa Period, when Japan was a feudal society, ruled by daimyo (lords), shoguns (generals), and samurai (aristocratic warriors). In 1868, the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown and a traditional monarchy was reinstated, beginning the period known as the Meiji Restoration, after the ruling Emperor Meiji. After re-opening its gates to the world, Japan was in a state of rapid modernization and Westernization, which were considered synonymous at times.

Photography, a modern invention, was introduced to Japan in the 1850s. (The first datable photographs taken in Japan were shot in 1854 by daguerreotypist Eliphalet Brown, Jr., who accompanied Commodore Perry on his expedition.) Originally met with widespread hostility and resistance, it was not until the 1860s that photography grew in popularity. The Japanese word for “photograph” is shashin, meaning “reproducing reality” – a translation that is only partially true. There was a significant Western market for tourist photographs of Japan, particularly since no foreigners were previously able to enter the country for hundreds of years. These photographs were often contrived, exoticized images of feudal Japan, sold as both landscapes and studio portraits of “native types.” However realistic or not they actually were, these photographs are fascinating documents of an antiquated, romantic view into a culture that was changing at breakneck speed.

Felice Beato

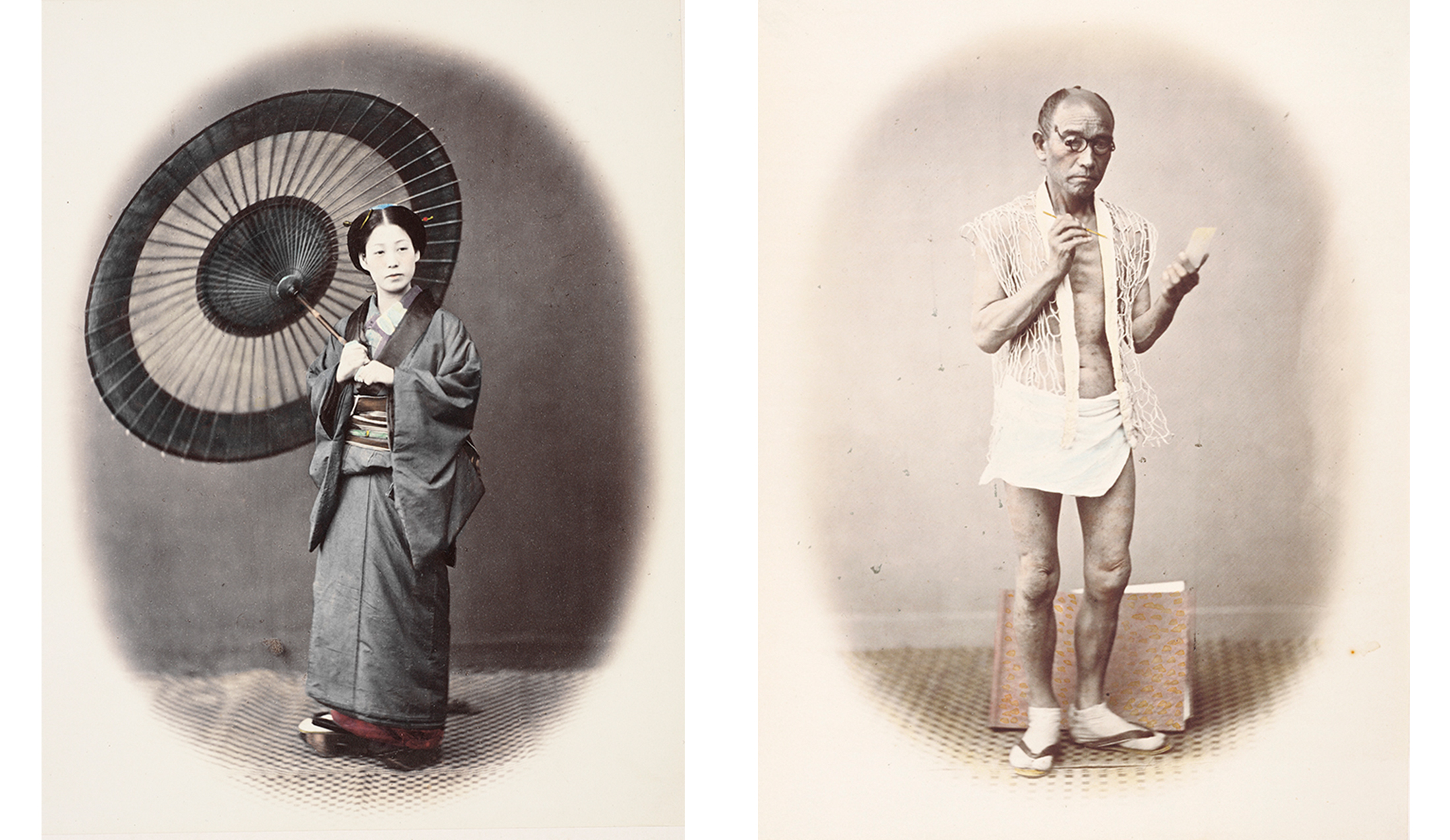

The most well-known and influential photographer in 19th-century Japan was actually not Japanese at all. Felice Beato was an Italian-British photographer who worked in Japan from 1863 until 1884. His photographic albums are unique visual documents of the last years of the country’s feudal period, 1865–68. His work was hugely influential to all subsequent 19th-century Japanese photography, particularly with his albumen prints which were hand-colored by Japanese artists. Many of these artists were formerly employed by coloring woodblocks for the production of ukiyo-e prints; Beato photographed one such painter from his studio (see below). (Click here to see Amanda Shubert’s discussion of this popular art form, which photography supplanted in popularity in the second half of the 19th-century.) Beato’s work is closely related to the ukiyo-e tradition in production and aesthetics; his studio portraits of geisha and tradespeople are quite unlike the picturesque and sentimentalized commercial photographs of his time.

Left: Felice A. Beato. British, born Italy, ca. 1825–ca. 1904. The Belle of the Period, ca. 1868. Albumen print with hand coloring mounted on cream colored paperboard. Purchased with the Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. SC 1982.38.2.13.

Right: Felice A. Beato. British, born Italy, ca. 1825–ca. 1904. Our Painter, ca. 1868. Albumen print with hand coloring. Purchased with the Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. SC 1982.38.2.45.

Baron Raimund von Stillfried

Felice Beato’s legacy was carried on by his contemporary competitor, Baron Raimund von Stillfried, an Austrian nobleman. From 1871 until 1885, Stillfried lived and worked in Yokohama, the largest city for exporting photographs, where Beato also had his studio. He was the first European photographer to use Japanese apprentices. Stillfried’s most famous photographic album, Views and Costumes of Japan, includes the last depictions of samurai warriors taken before they were no longer allowed by law to wear their topknot hairstyle or carry swords, symbols of their aristocratic status which was dismantled with demise of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Left: Baron R. von Stillfried. Austrian, 1839–1911. Three Japanese ladies with hands entwined, 1875–1885. Albumen print with hand coloring. Purchased with the Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. SC 1982.38.1014.

Right: Baron R. von Stillfried. Austrian, 1839–1911. Portrait: Old Beggar, 1875–1885. Hand-colored albumen print. Purchased with the Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. SC 1982.38.1016.

Kusakabe Kimbei

One of Stillfried’s Japanese apprentices was Kusakabe Kimbei, who became a commercial photographer with his own studio in Yokohama. His and Stillfried’s photographs are instilled with a psychological sense of their subjects that is lacking in the work of Beato. While he worked in relative obscurity during his lifetime, Kimbei is now one of the most renowned Japanese photographers of the 19th-century. Pictured below are works by Kimbei which the Smith College Museum of Art acquired recently.

Kusakabe Kimbei. Japanese, 1841–1934. Umbrella Maker, 1880s. Albumen print with hand coloring. Purchased with the fund in honor of Charles Chetham. SC 2011.31.1.

Kusakabe Kimbei. Japanese, 1841–1934. Vegetable Pedler, 1890. Albumen print with hand coloring. Purchased with the fund in honor of Charles Chetham. SC 2011.31.2.