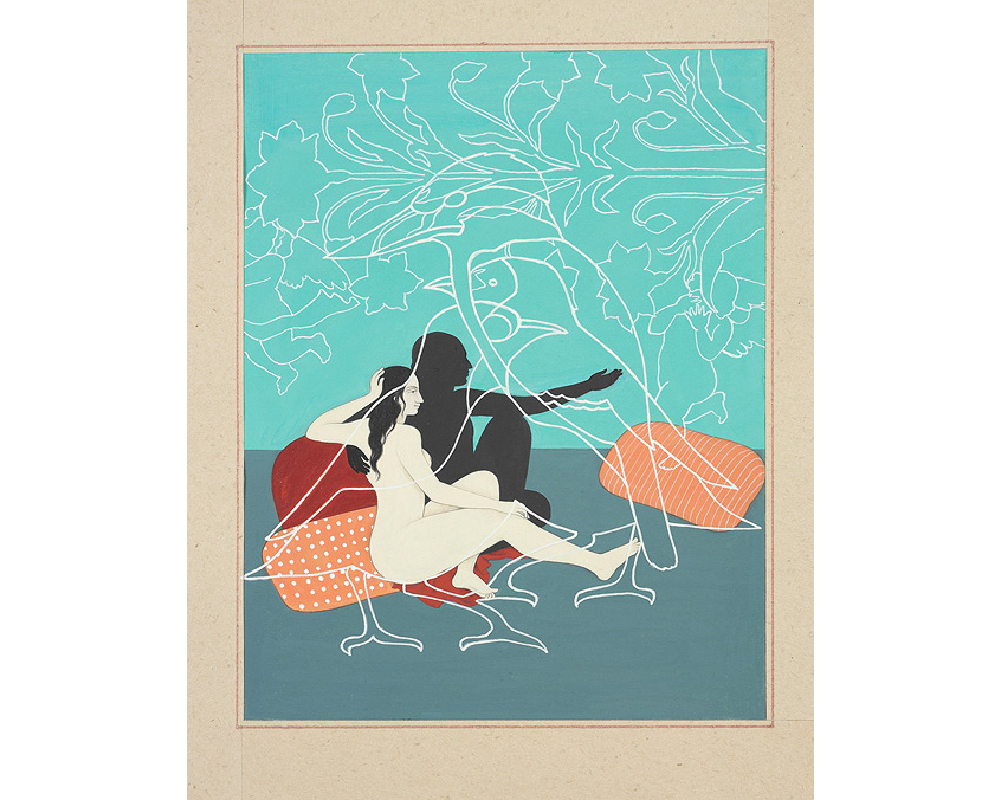

Three Songs of Devotion

Guest blogger Thalia Berard is a Smith College student, class of 2015, majoring in Art History. She wrote this post for Islamic Art and Architecture, a course which surveys the architecture, landscape, book arts and luxury objects produced in Islamic contexts from Spain to India, and from the seventh through the twentieth centuries. The Fall 2014 session was taught by Professor Alex Dika Seggerman, the Five College Post-Doc in Islamic Art & Architecture.

Born in Lahore, the capital city of Pakistan, Nusra Latif Qureshi studied classic miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore. In 2001, she immigrated to Australia to continue her studies postgraduate at the Victorian College of the Arts at University of Melbourne, where she continues to work as an artist today. Qureshi’s work is built both on the traditional Mughal painting style she honed in Lahore and her own contemporary painting style born from her studies in Melbourne.

Three Songs of Devotion represents her earlier work, as it is dated to 2002, a year after Qureshi immigrated to Melbourne. Her perspective of being both Middle East-born and immigrant has led to her using well-known symbols from South Asian and Middle Eastern art combined with her own boldly minimal style to illustrate the difficulties she’s faced in crossing cultures and identities.

Detail of female figure

In addition to studying miniature painting in Pakistan, Lahore also studied the technique in India, inspiring her to adopt Hindu cultural motifs into her works. Gardens of Desire II, for instance, depicts two such Hindu divinities, lovers Radha and Krishna, by referencing an eighteenth century Hindu painting Krishna and Radha in a Pavilion.

Detail of bird drawings

While Three Songs of Devotion may not make as direct a reference, Qureshi’s choice to represent the male figure as a basic outline and the female figure in detail calls into question traditional gender roles in Mughal painting, a field typically dominated by men, by showcasing the woman in the painting. The overlay of line drawings recalls the British colonization of India, as the British were instructed to record and document native Indian plants and wild life. The angelic figures take the reference to Western invasion one step further, harkening back to putti that populated European Renaissance paintings.