acquisition highlights

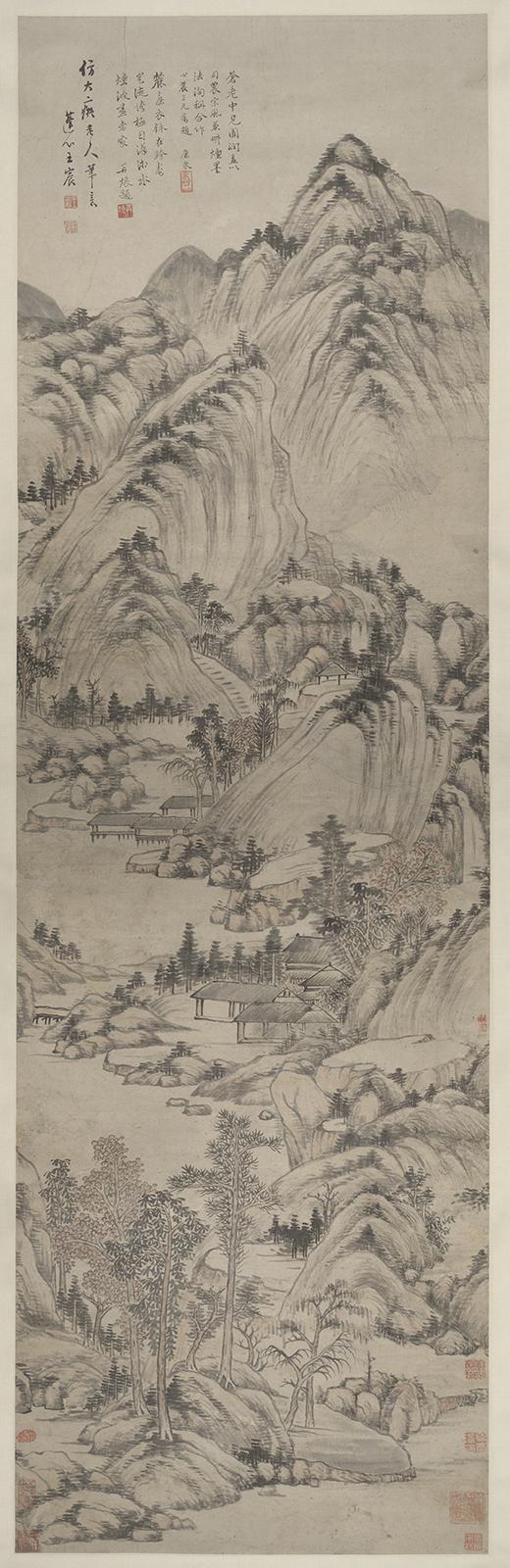

wang chen

WANG CHEN. Chinese, 1720–1797

Landscape after Huang Gongwang, 18th century

Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper

Purchased with the Carroll and Nolen Asian Art Acquisition Fund SC 2022.26

Artistic lineage plays a significant role in the East Asian ink painting tradition. Two colophons (inscriptions) at the top of this landscape painting by Wang Chen mention the legacies of Wang Yuanqi (1642–1715) and Wang Hui (1632–1717)—two of the Four Wangs of the so-called Orthodox School of landscape painting in China’s Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Born into a distinguished family of scholars, officials and painters, Wang Chen was the great-grandson of Wang Yuanqi. He held government positions and socialized in elite literati circles. His achievements as an artist in his own right earned him recognition as one of the Lesser Four Wangs, who carried forward their early Qing ancestors’ heritage.

Lineage is traced through not only family ties, but also stylistic emulation. In Landscape after Huang Gongwang, Wang Chen blends wet and dry brushwork and applies darker strokes over lighter ones, overlaying them to shape up landscape forms. The entire painting is built up almost modularly, without much indication of atmospheric perspective. This style is typical of what is recognized as the Literati School of painting, theorized and promoted by Ming dynasty (1368–1644) artist, collector and writer Dong Qichang (1555–1636). Wang Chen, along with the other Wang artists of the Qing dynasty, following Dong, emulated the style of one of the Four Masters of the preceding Yuan dynasty (1271–1368): Huang Gongwang (1269–1354). The artist’s inscription on the far left explicitly acknowledges the source of inspiration: “imitating the brush concepts of old Dachi (i.e., Huang Gongwang).” Huang’s almost impressionistic brushwork and his view on landscape painting contributed to the foundation of Literati painting.

Literati landscape painting is taught regularly in Asian art courses as a high point of the ink tradition. Because of their rarity and high artistic as well as art-historical value, works by Huang Gongwang, Dong Qichang and the Four Wangs are virtually impossible to come by. This newly acquired painting by Wang Chen in the style of Huang Gongwang offers a compelling example to shed light on Literati landscapes and the importance of artistic lineage.

ethel myers

ETHEL MYERS. American, 1881–1960

The Flowered Gown, 1920s

Bronze

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Barry Downes (grandson of Ethel Myers)

SC 2022.40.1

This small-scale bronze sculpture is the first work by Ethel Myers to enter the collection. It fulfills one of the current aims of the SCMA Collecting Plan: to acquire more historic works by women artists, particularly sculptors.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Mae Ethel Klinck trained as a painter at the Chase School of Art and the New York School. Although she did not identify herself as an artist of the so-called Ashcan School of American realism, she studied with Ashcan founder Robert Henri as well as William Merritt Chase. She painted contemporary life, particularly in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, which was mostly inhabited by immigrants living in tenements at the time.

In 1905, she married Jerome Myers, who was also a painter of urban realism. One year later, they welcomed a child. From then on, Ethel Myers traded painting for small-scale sculpture and largely put her own career on hold in order to support her husband’s work and to tend to their child. Her interest in modern society continued to find expression through commissioned portraits and caricature-like images of city-dwellers, many of them humorous. She exhibited nine of her small sculptures at the 1913 Armory Show to great acclaim. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that “she is worthy of a place alongside of Daumier, Meunier and Mahonri Young.” Through this comparison to three well-established artists who also focused on the vicissitudes of modern life, she gained further credibility in the male-dominated art world that she continued to navigate. Between 1920 and 1940, Myers took on additional work to support the family, which included designing clothes and hats for local New York celebrities.

One of three posthumous casts, The Flowered Gown demonstrates the artist’s interest in character types and fashion. These sculptures are often referred to as caricatures, but Myers preferred to view them as portraits. This sculpture seems to exude the personality of the woman through her pose, expression and dress. The exaggerated elegance of the figure pokes fun at the importance of fashion to upper-class New York women.

In addition to the bronze sculpture, SCMA acquired the ceramic mold for The Flowered Gown as study object (SC MP 2022.40.2). This mold was used to create the SCMA bronze and two others like it, providing a window into Myers’ artistic process. After modeling the figure in terracotta, she poured liquid metal into a ceramic shell to create a bronze cast. While ceramic molds are sometimes discarded after use, this one survived and was preserved through glazing.

The Flowered Gown and its mold join several related works in the SCMA collection. These include three prints by Myers’ husband, Jerome Myers, as well as several paintings and works on paper by her instructors William Merritt Chase, Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller. Myers’ bronze also resonates with other sculptures in the collection, such as the caricature of Dr. Prunelle by Honoré Daumier and sixteen other works by nine American women sculptors created before 1950.

pablo picasso

PABLO PICASSO. Spanish, 1881–1973

Tête de Femme (Head of a Woman), 1921

Sanguine chalk and charcoal on medium-weight, slightly textured cream-colored paper Bequest of Judy Emil Tenney, class of 1949

SC 2023.21

Pablo Picasso is one of the most recognized figures in 20th-century European art. SCMA is fortunate to hold a strong collection of art from all of the artist’s major periods, including ceramics, drawings, illustrated books, paintings and prints. This important drawing bequeathed by Judith Emil Tenney, class of 1949, has added depth to SCMA’s holdings of Picasso’s drawings, which before this gift included only three small sketches.

Tête de femme (Head of a Woman) was made during a transitional time in Picasso’s artistic development. From 1918 to 1925 he worked simultaneously on Cubist still lifes as well as portraits and figure studies informed by his renewed study of classical art. In the years after World War I, many European artists, including Picasso, embraced the simplicity and order of classicism as an antidote to the destructiveness of war.

The identity of the sitter for this drawing is difficult to determine, as Picasso’s classical figures often bear idealized rather than individualized features. The artist’s first wife, Olga, is presumed to be the model for many of Picasso’s works of this period. However, this drawing and several other works from the early 1920s are believed to be likenesses of the Jazz Age socialite Sara Murphy, identifiable by her features and wavy hair. During this period, Picasso was moving away from portraiture and toward more universalized figures.

The woman’s deep-set, downturned eyes, roman nose and bow-shaped lips are rendered with softly blended chalk outlined with charcoal. Her loosely arranged hair, tumbling over her shoulders, is boldly sketched in thick lines of red and black. These contrasting techniques form an image that speaks to the best of Picasso’s work as a draftsman.

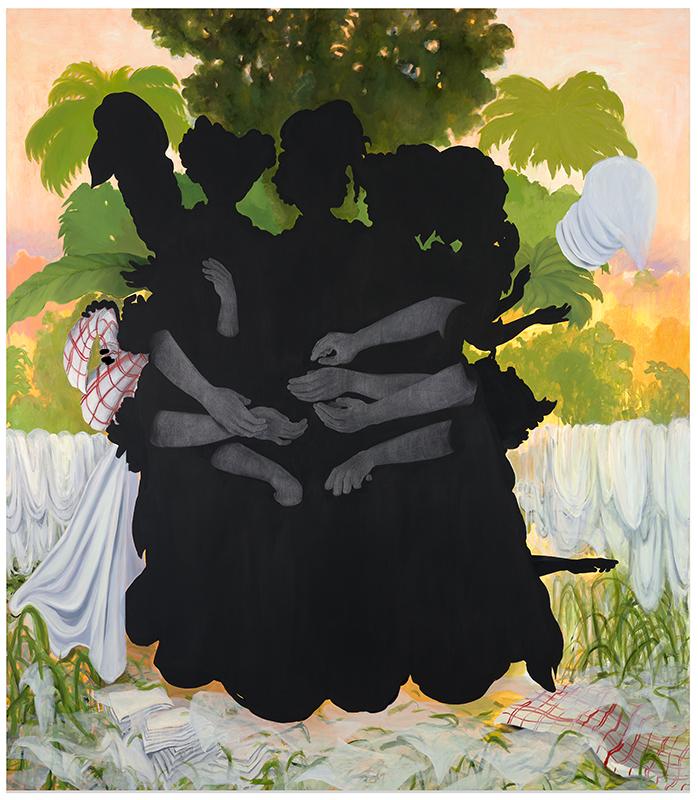

alexis callender

ALEXIS CALLENDER. American, b. 1980

Where Everything is Made From Within, 2019

Oil, acrylic and graphite on canvas

Purchased with the Dorothy C. Miller, class of 1925, Fund

SC 2022.30.1

Where Everything is Made From Within, along with the related preparatory drawing, A Study for Conjuring (2019; SC 2022.30.2), is from Alexis Callender’s series of more than three dozen paintings and drawings entitled Difficult Love (What Scatters and Then Comes Back Together). These two contemporary artworks forge connections across SCMA’s holdings, supporting SCMA’s priorities of collecting and teaching from art that is expansive in its aesthetic, thematic and art-historical scope. The painting, like the series overall, emerged from Callender’s research into the interior lives of Black women and women of color in the colonial Caribbean and her reflection on the role of visual representation—painting in particular—in the construction of history.

The large central figure of Where Everything Is Made From Within is a matte black silhouette, with seven heads and many hands suggesting either multiple bodies pressed closely together or, alternatively, a reinterpretation of the Hydra, a multiheaded beast from ancient Greek mythology. Layered over the silhouette, as if emerging from sleeves or from another dimension, are eight gray hands and arms. White and red-and-white checkered cloths (a reference to madras cloth, which was imported from India) and translucent sheets—paper, perhaps—are scattered and draped below and beside the figure(s). While the central figure(s) and vertical orientation situate the painting within conventions of portraiture, the canvas also contains a parallel reflection on landscape. Callender plays with the visual language of tropical landscapes that circulated both in European and U.S. American art and visual culture and in contemporary tourism campaigns. The bright green palm leaves and the orange-sherbet glow of the sunset resist resolving into the cliché at which they nod.

In the Difficult Love series, Callender reflects on the possibilities and constraints of depicting in paint what she terms “a colonial Caribbean worlding” that neither conceals nor reproduces violence. She does so in part through a conversation with the work of Agostino Brunias (c. 1730–1796), an Italian painter commissioned by the British government to paint daily life in Caribbean colonial and slave societies. For Callender, a multifaceted set of problems and questions that interest her—historical, methodological, aesthetic, ethical, economic, sociopolitical—coalesce around Brunias’ romanticized depictions and the women contained therein. Can the strictly raced and gendered hierarchy that Brunias constructed for his figures, who appear as types rather than individuals, be re(con)figured? What forms of resistance, love and worldmaking were available in Caribbean colonial and slave societies? How is it possible to imagine and depict today the inner worlds and shared complicities of and between Black women and women of color from previous centuries? Could the silhouette, which removes the face, and a focus on arms, hands and gestures offer another way into interiority?

In Callender’s words: “[M]y intervention in these colonial works is to create a speculative past, but one that aligns more with the historical record. Where Black women and women of color are not used as pictorial agents to uphold and reify European fantasies of island and naturalizing racial subjects. In these works, I have tried to render these women not as a historically contested body, but as women with large interior worlds in which the possibilities of time and space and love are still unfolding over water and under sky.”