From Home: An Interview with Camille Bacon ’21

Sophie Poux is a student assistant at the Cunningham Center, a Government major, and a member of the class of 2021. From Home is a series of interviews she is conducting remotely this year.

Camille Bacon is a member of the class of 2021 and a major in Africana Studies. She is also the inaugural recipient of the Cromwell Fellowship, which has supported the preliminary research for her honors thesis. You can read Camille’s new blog here, and see what she wrote for SCMA Insider about Barkley L. Hendricks’ work “Lawdy Mama” on view as part of Black Refractions at SCMA last year here.

Camille and I spoke last month about the upcoming event she is organizing to bring Kimberly Drew ’12, Thelma Golden ’87, Jenna Wortham, and Amanda Williams together virtually. She also told me about how Black Refractions (on view at SCMA last year) changed her life, the expectations of Black artists and Black art, and her mom’s advice for getting in touch with Thelma Golden.

I would love to hear you talk about your experience seeing Black Refractions (which is currently on view at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts) at SCMA last year.

This is an example of future Camille showing up for past Camille and then past Camille showing up for future Camille. I got the email that all students received with the opportunity to sign up for a tour of Black Refractions. I had never heard of the Studio Museum, and I didn’t even know what curators do! But I signed up for a tour of the show with Emma [Chubb, Charlotte Feng Ford ’83 Curator of Contemporary Art at the Smith College Museum of Art] on a whim.

At the time, I didn’t understand that I could be in the art world without being an artist. My mom is French, so there was always big time nerd culture in my family. We visited museums all of the time when I was growing up but I never felt reflected on the walls and never understood what that even felt like.

Walking into Black Refractions was, quite simply, amazing. This experience of never being reflected on museum walls is a very common experience for many non-white people, but especially for Black women. Seeing myself reflected on the walls made the space feel safer, feel more blissful. More possibilities were engendered merely by that feeling that belong in that space.

Left: Barkley L. Hendricks. American, 1945–2017. Lawdy Mama, 1969. Oil and gold leaf on canvas. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Stuart Liebman, in memory of Joseph B. Liebman. © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and American Federation of Arts.

Right: Isaac Julien, Incognito, Barkley L. Hendricks, Lawdy Mama on view in Black Refractions at SCMA. Photography by Stephen Petegorsky for SCMA.

Isaac Julien. British, b. 1960. Incognito, 2003. Plaster, urethane foam, urethane plastic, acrylic paint, cloth, and human hair, 73 1/4 × 29 1/2 × 19 3/4 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of the artist and Mr. Melvin Van Peebles 2004.5.24.

On another level, I have always been a very curious person but not necessarily known where to apply all of that energy and electricity. During that tour, I asked Emma so many questions that we only made it through the first floor. We didn’t even get to the lower level where all of the former artists’ in residence works were! It felt like I had finally found a vessel that was large enough to hold my curiosity. There’s always another artist, another concept, another theorist that I can be learning about. That I’ll never know all of it is daunting but also galvanizing.

I was previously pre-med, but once I saw Black Refractions I decided that I could never go back. I decided I was changing my course of study for good and I began to imagine myself conducting a career in the art world. I didn’t necessarily know what I was getting myself into but I had a deep sense of knowing that this was the right thing for me to do. Without much second thought, I just did it and waited for the pieces to fall into place. Black Refractions was a transformative, spiritual, blissful experience and I will never, ever, ever, ever forget it.

What did you do next?

I had mentioned on the tour that I’m from Chicago, and Emma [Chubb, Charlotte Feng Ford ’83 Curator of Contemporary Art at the Smith College Museum of Art] later emailed me about an internship at the Art Institute of Chicago. Emma clearly saw what I see in myself now before I did. I did a ton of research about Thelma Golden, about the Studio Museum in Harlem, about Kimberly Drew [’12, art curator and writer]. Charlene Shang Miller [Associate Museum Educator for Academic Programs at SCMA] invited me to a student lunch with two people from the Studio Museum, one of which was Shanta Lawson who runs Education there. She spoke a bit about the internships and I got really interested. Then, I saw that Kimberly had interned for Thelma, and so I decided to apply. When I got an interview, I screamed at the top of my lungs. My parents thought I was being murdered! All of that was put on hold when COVID happened which was such a letdown.

However, I ended up receiving the Cromwell Fellowship which allowed me to do research for my thesis, so it all worked out. If it weren’t for Black Refractions, this would not have happened. Everyone who was involved in getting Black Refractions to SCMA changed my life. I really believe that to be true.

That is so moving, and I’m so happy for you. You were really in the right place at the right time. Even if you were the only person for whom that show was really important, that would be enough. But I know that you’re not.

Yes. I’d love to have a club of people who are just obsessed with that show so we can gush over it.

Tell me about the event you’ve organized for next month.

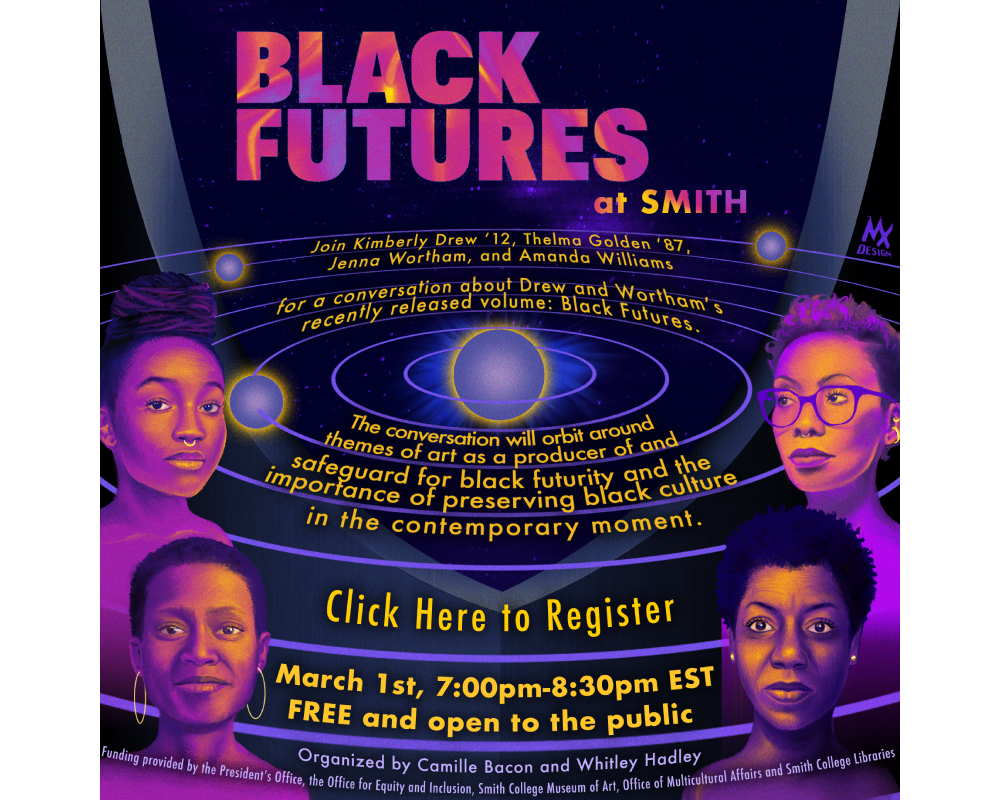

On Monday, March 1 at 7 pm, EST, Kimberly Drew ’12, Thelma Golden ’87, Jenna Wortham, and Amanda Williams are gathering for a conversation about Kimberly and Jenna’s recently released book, Black Futures. Amanda is one of the artists in the book and Thelma’s work is so important and relevant to this project. The discussion will orbit around themes of art as a producer of and safeguard for Black futurity and the importance of preserving Black culture in the contemporary moment. Kimberly is also winning the Smith Medal this year, so it feels like really good timing. I think everybody should know who all four of these panelists are. They’re doing the most incredible work, they really, really are. You can RSVP here!

How did this come together?

When I got the Cromwell Fellowship through the Africana Department and the President’s Office in May, the Grécourt Gate ran a story about my project which basically served as preliminary research for my thesis. A recent Mount Holyoke alumni, Emma Taylor, saw the story and reached out to tell me that she had been trying to bring Kimberly to campus, but that COVID had completely botched these plans. She connected Kimberly and I hoping that I would be able to bring her to the Pioneer Valley this year. I had previously watched a recent lecture Kimberly had given in which she mentioned that she needed an intern to help archive her Black Contemporary Art Tumblr blog. I reached out to her about this and she began to give me projects to work on. She’s been doing this thing called Black Power Lunch Hour where she interviews cool Black people on Instagram – herbalists, healers, fine artists, really everyone under the sun – and I was also helping her transcribe all of those episodes so that she could post transcripts. Meanwhile, she was interested in this idea of doing an event at Smith and I now felt like I had my foot in the door as we were building a rapport through these projects I had been working on.

I had also been trying to get in touch with Thelma Golden – I don’t even want to imagine what her email inbox looks like – but was having some trouble. One day my mom and I were having breakfast and she just said, you have her address through the Smith Alumnae Directory, why don’t you just send her a letter? So I wrote and mailed her a letter talking about how Black Refractions changed my life. Thelma emailed me back and said she would love to chat! She mentioned how much she loves Smith and that she would really love to speak on campus.

At this point, I was in the preliminary stages of my research which now focused on Thelma’s show, Freestyle, at the Studio Museum in 2001. Since seeing Black Refractions, interning with Kimberly, and talking to Thelma, it felt like everything was happening. Even though it was May and June when COVID was supposed to be dissipating but wasn’t, this was a really exciting time. It was really lovely to have this brainchild operation happening.

When I found out about Black Futures (by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham, published December 2020), I knew that I wanted them to talk about this book. I thought it would be great to invite Jenna, too. And how fantastic would it be if we had Thelma there as well? I had also been in touch with Amanda Williams following her residency at SCMA. In addition to being one of the artists in Black Futures, we’re both from Chicago, and Chicagoans stick together.

Once I had confirmed that Kimberly and Thelma were down, I began emailing a bunch of different offices at Smith about funding. I reached out to Charlene at SCMA, I reached out to President McCartney, I reached out to Nimisha Bhat [Visual Arts Librarian]. This was a really uncertain time – lots of offices’ budgets were being cut – but everyone was super enthusiastic about the idea and just told me to make a budget and that they would figure it out.

And now it’s happening! It feels like this event came together overnight even though of course that’s not the case. I’ve been working closely with Whitley Hadley [Assistant Director] from the Office of Multicultural Affairs to put it together and she’s just been amazing. We also commissioned Max Aguilar – they’re so great! – who is an artist from Chicago to make a poster. This event has been super hush-hush for a long time and I’m so excited to be telling people about it.

I attribute so much to the excited and generous reception of the offices that I reached out to. I think that administrators believing in students is such a Smith thing. It’s not cheap to put together an event like this, which is one of many things I’ve learned while putting this together.

David Hammons, African-American Flag; Beauford Delaney, Portrait of a Young Musician on view in Black Refractions at SCMA. Photography by Stephen Petegorsky for SCMA.

Left: David Hammons. American, b. 1943. African-American Flag, 1997 Printed fabric stapled on a painted wooden pole. Flag: 8 x 11 in.; pole: 18 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem.

Right: Beauford Delaney. American, 1901–1979. Portrait of a Young Musician, 1970. Acrylic on canvas, 51 x 38 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of the Estate of Beauford Delaney 2004.2.27. Photo Credit: Marc Bernier. © 2018 Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator. Courtesy American Federation of Arts.

I’m so excited for you and also selfishly excited that I get to attend.

Which is great! This doesn’t work unless other people are excited about it too.

I’m also really interested in the book itself. I don’t know if you’ve been following Kimberly Drew or Jenna Wortham on social media, but they keep using the word “archive” to describe the book. I’m really looking forward to diving into why that specific term encapsulates the project.

I’ve listened to a couple of podcasts where they’re talking about their decision process for what went into the book. I’m really looking forward to hearing about how it felt to make those decisions and what their parameters were. Was it an emotional thing? What were the benchmarks, the criteria? But also, I’m thinking about that power of deciding what goes in the archive. There’s an agency that Kimberly and Jenna held in making the decisions about what went in the book.

It also feels really special that I get to do this as part of my last semester at Smith. My time at Smith has been really academically rich, but it hasn’t been easy. This feels like a good way to end my time at Smith on a high note.

Tell me about your thesis.

I believe strongly that Black contemporary artists’ work is always filtered through the question of “what is this telling us about the ‘Black experience’?” And Black people do this too. We are all victim to this trap. My thesis is about exploring where that question came from and why we ask it, because it has its roots in history, it definitely didn’t come out of nowhere.

There are these expectations of Black artists which began with, for example, W.E.B. DuBois saying things like “all art is propaganda and ever must be.” In the context of the 1920s when Jim Crow had become vehement throughout the entire country but especially in the South, there was a resurgence of visual tropes of blackness. To counter that, the aesthetic mood of the time was of uplift and positive images to counter those stereotypes. Subliminally, then, there was an expectation of Black artists to address race and make images of uplift. But this limited artists from diving into their own aesthetic proclivities. What if they wanted to make abstract, non figurative work? Well, there were people who were actively discouraging Black artists from doing so, DuBois being one of them.

Five works on view during Black Refractions in the lower level galleries. Photography by Stephen Petegorsky for SCMA. From left to right: Nari Ward, All Stars; Kerry James Marshall, Silence is Golden; Willie Cole, Steam’n Hot; Leonardo Drew, Number 74; and Kehinde Wiley, Conspicuous Fraud Series #1 (Eminence) on view in Black Refractions at SCMA.

Nari Ward. Jamaican, lives and works in New York, NY, b. 1963. All Stars, 1995-96. Baseball bat, ironed cotton, nails, medical tape, and sugar, 33 1/2 × 5 × 5 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of the artist 1997.1.

Kerry James Marshall. American, b. 1955. Silence is Golden, 1986. Acrylic on panel, 49 × 48 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of the artist 1987.8.

Willie Cole. American, b. 1955. Steam'n Hot, 1999. Steam iron and feathers, 10 × 4 1/2 × 12 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn 1999.5.1.

Leonardo Drew. American, b. 1961. Number 74, 1999. Rust, fabric, string, stuffed toys, and wood, 97 × 96 1/2 × 9 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Sue Stoffel 2008.20.1 25.

Kehinde Wiley. American, b. 1977. Conspicuous Fraud Series #1 (Eminence), 2001. Oil on canvas, 72 1/2 × 72 1/2 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Anne Ehrenkranz 2002.10.14.

In the 1960s, there was a resurgence of these expectations aligned with the Black Power Movement. But this movement wasn’t so much about uplift as it was about asserting how beautiful blackness is. Not only are we human, too, but we, too, are beautiful, and we, too can make art. However, this was still coming from within the deeply nationalist, deeply masculine, deeply essentialist, separatist ethos of the Black Power Movement. There was a turn away from any visible white, European influence. But what does that – white influence – even mean, right? And, again, there was still this notion that Black artists should be speaking to the race and they should be making images that align with this militant, masculinised, essentialist ethos.

One example is the AfriCOBRA Collective, who used a Kool-Aid color palette made up of bright colors and no white to make explicitly political work. Because of all this, there was a subliminal admonishment of artists who were working in more experimental and abstract forms.

On the other hand, Howardena Pindell was an artist using a hole puncher to make weird, abstract art. She was actively discouraged from making this work and accused of pandering to the white world. There’s this strong association between abstraction and whiteness. And in my thesis, I’m trying to express that it is the case but doesn’t need to be.

Then we reach the 2000s. Thelma Golden curated the show Freestyle, her first show at the Studio Museum, in 2001 for which she coined the term “post-Black.” She defined post-Black as not necessarily a unifying aesthetic or a particular way of making work but as a vibe, as a feeling, as a particular stance on what it means to be a Black artist without necessarily having fidelity to other people defining you as a Black artist. These expectations that we’ve been talking about are still actively limiting Black artists’ ability to just go weird with it, to go hole-puncher-Howardena-Pindell with it. But Thelma refuses: she says no, all of these artists are already making weird art and I hope that they continue to. This became really, really controversial.

The term post-Black was basically ignored at the beginning of the exhibition. Not a single review of the show that I’ve read takes up the term in depth. Some mention it but they don’t linger until the following year when someone begins to ask the artists in the Freestyle who now have gallery representation and are taking off in the mainstream art world, what do you think of “post-Black”? And some of these artists say, well, I think it’s a cool idea but how could we ever be “post-Black”? In other words, they begin to interpret post-Black as post-race, which is not at all what Thelma meant.

Left: Chakaia Booker. American, b. 1953. Repugnant Rapunzel (Let Down Your Hair), 1995. Rubber tires and metal, 33 x 25 x 22 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Friends and Family of Chakaia Booker 1996.7. Photo Credit: Nelson Tejada. © Chakaia Booker. Courtesy American Federation of Arts.

Right: Jordan Casteel. American, b. 1989. Kevin the Kiteman, 2016. Oil on canvas, 78 x 78 in. The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition Committee 2016.37. Photo Credit: Adam Reich. © Jordan Casteel. Courtesy American Federation of Arts.

The world wasn’t ready for this in 2001, but on some level, Thelma’s intervention worked. Now, we have artists working in new media, working in performance; they’re going weird with it! I can’t contest that, in the 20th century, it was deeply necessary that these expectations be held and that artists claim being Black artists. But what I can begin to highlight and bring to our attention is how detrimental these expectations are to us and to all Black artists that are working in this current moment. Now, Black people are in the room but the room is still violent.

Black artists are constantly asked why and in what way their art is Black. But maybe their art is not about that at all. Maybe – and this is a shocker to some people – maybe Black people exist as people who are Black and not ‘Black people’ in the same way that Black artists exist as artists who happen to Black, not as ‘Black artists’. I think this has a direct bearing on the sort of ideological frameworks that we have to apprehend the work. Why does art criticism and analysis always have to be situated in social histories?

I’m interested in showing that this artwork is inscrutable and never generates an understanding or knowing of blackness. Blackness is something that can never be known or understood, and this project of trying to understand blackness through the work of Black artists is futile. I want to say, just let us be unknowable and opaque and somewhere you cannot access. And this is the proverbial “you,” not necessarily only non-Black people. I think Black people can be inscrutable to each other in a really interesting way, too.

Legacy Russell [Associate Curator of Exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem] writes in her book Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto about knowing and naming. Every time we try to make something knowable, it’s wrapped up in the movement to commodify things and make them usable. It’s ultimately about trying to structure labor. How can artists ever exist within that framework when what they’re doing is so antithetical to this capitalist neoliberal hellscape that we’re all existing in? Russell writes about how, when we name things, we end worlds. By naming something you reduce it, and by reducing it, you severely limit the possibility of what the named thing can do.

When I asked Camille if there are works in SCMA’s collection that have left an impression on her, Emma Amos’s One Who Watches (above) was the first she mentioned. She noted the historic significance that this work was purchased with a gift from the Black Students Alliance, the presence of Manet in the border of the work, and how she hopes that SCMA will one day exhibit this work side by side with those of Amos’ inspirations, including Manet.

Emma Amos. American, 1937–2020. One Who Watches, 1995. Acrylic on linen, heat transferred photographs on muslin collaged onto canvas, African Kanga cloth borders and cotton broadcloth fabric strips sewn onto linen. Purchased with the gift of the Smith College Black Student Alliance 1999-2000. SC 2001.1.

We can think about the phrase “Black artists” as a name which carries with it all of these assumptions and expectations that their work is going to “look Black.” When we obliterate the name, we end up in this elastic, slippery space where nothing can quite be pinned down. That is so scary to many people who deeply want to commodify Black artists and Black art. The hard part of discussing these things is that it’s all subliminal. I’m guilty of these things, too.

So this is the project that I’m invested in: by paying attention to where these expectations come from, can we begin to take them apart? How can we do this in service of creating space for Black artists to do whatever they want without the burden of expectation?

Comments

I love this interview. So…

I love this interview. So much food for thought. Can't wait for the Black Futures event!!