Where are all the Women Artists?

Danielle Carrabino is the Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Smith College Museum of Art.

Many visitors to the Smith College Museum of Art arrive with the expectation that the majority of the collection will be by women artists. However, even at Smith College, one of the most established women’s colleges in the United States, this is not the case. We are often asked why. History has not been kind to women artists. With a few exceptions, women were often excluded from artistic training until the 19th century. As a result, artists in Western society are usually assumed to be male. Women who sought careers as artists did not conform to the traditional roles ascribed to them. Furthermore, many of the artists who have been the subject of scholarship and history books are overwhelmingly male. This has led to the misconception that skilled women artists only existed in small numbers or worse, that women were not suited to the profession. None of these reasons are acceptable and all of them require revision.

In the past few decades, museums have acknowledged the lack of women in their collections and several have committed to acquiring more art by women. See, for example, the commitment by the Baltimore Museum of Art to acquire only art by women in 2020. While it is easier to find works by women from the 20th century on, locating historic art by women on the art market is more challenging. Between 2019 and 2020, the SCMA added four works to the collection by historic women artists, spanning the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Lavinia Fontana. Italian, 1552–1614. Portrait of a Man and Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1585–1599. Oil on panel. Purchased with the Dr. Robert A. and Minna Flynn Johnson, class of 1936, Acquisition Fund. SC 2019.14.1 & SC 2019.14.2.

It is no coincidence that two of these artists are Bolognese. The city of Bologna has the distinction of being an artistic center in Italy that produced a comparatively large number of women artists. Lavinia Fontana and Elisabetta Sirani were both trained by their fathers but soon surpassed them in fame to forge successful careers for themselves. It is exciting to be able to present works by both of these women to tell the story of women artists working in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. For more on these artists, see this blog post from 2019 about SCMA’s acquisition of two works by Lavinia Fontana and this blog post about SCMA’s acquisition of the self portrait by Elisabetta Sirani last year.

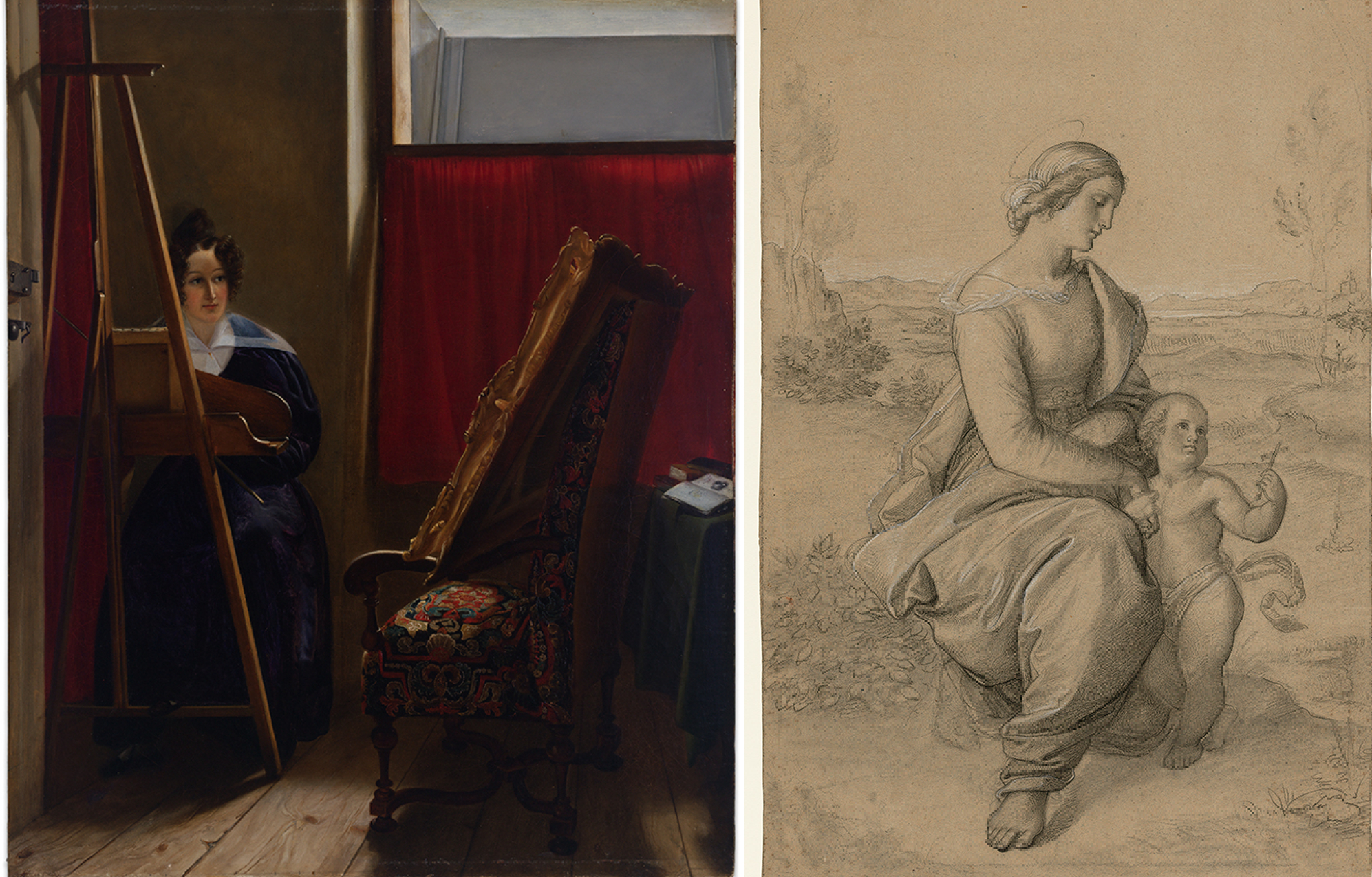

Left: Amile-Ursule Guillebaud. Swiss, 1800–after 1880. Portrait of the Artist, Seated at her Easel, ca. 1820-1845. Oil on canvas. Purchased with a gift from Peter Soriano and Nina Nunk, class of 1988, and the Museum Acquisitions Fund. SC 2019.5.

Right: Maria Ellenrieder. German, 1791–1863. Virgin and Child in a Landscape (after Raphael), ca. 1822–24. Black and white chalk on thick, rough, tan paper. Purchased with the Madeleine H. Russell, class of 1937, Fund and the gift of the Almathea Charitable Foundation. SC 2020.7.2.

Two lesser-known artists who joined the collection are Amile-Ursule Guillebaud and Maria Ellenrieder. Guillebaud benefitted from living and working in Geneva, where she received artistic training in one of the few art academies for women in Europe. Similarly, Ellenrieder enrolled in an art academy as the first woman to do so in Munich, Germany in 1813. Although we may not recognize their names, these two artists deserve to be acknowledged and displayed in the museum alongside their male counterparts. Both of them provide topics for further research by Smith students and work toward the goal of creating greater equity in the collection between male and female artists.

All of these artists worked within certain prescribed genres available to women at the time, namely, portraiture. The value of adding two self-portraits of women artists to the collection is especially important as it provides a sense of how these women saw themselves and more importantly, how they wished the world to see them. Sirani’s assured gaze directly meets the viewer while Guillebaud portrayed herself at her easel in the act of painting. The copy of a painting by Raphael by Ellenrieder is a nod to the common practice of women artists who learned to draw and paint by copying from established (male) masters. With the exception of Guillebaud, about whom we still know so little, these artists also painted other genres usually considered ill-suited to women, thereby exceeding expectations.

By drawing attention to these four works of art, I do not intend to imply that we have solved the pervasive problem of how scarce women artists are in the SCMA collection. In fact, our work has only begun. These four women enrich the collection by offering new perspectives and provide stories that have not yet been told. My personal hope is that one day the concept of a woman artist will disappear entirely, and that they will be known as their male counterparts, simply as artists.