acquisition highlights

iranian tiles

Unknown. Iranian, Safavid dynasty (1501–1722)

Tiles from a Panel with Cup-bearer Design,

early 17th century

10 painted and polychrome-glazed stonepaste tiles,

cuerda seca technique

Gift of Jane M. Timken, class of 1964

SCMA was fortunate to be gifted 10 painted and polychrome-glazed stonepaste tiles from Jane M. Timken, class of 1964. They date to the early 17th century, during the Iranian Safavid dynasty (1501–1722). The tiles were part of a large garden scene created in a technique known as cuerda seca—literally, “dry cord”—in which colored areas are outlined over a glazed base. Seven of them form a figural panel representation of a saqi, or cupbearer, holding a ewer. The remaining three tiles are not pictorially connected but are nevertheless from the same group.

The tiles once decorated the west façade of the Jahan-nama pavilion, built about 1596–1602 during the reign of Shah Abbas I and located on the ceremonial avenue and promenade known as the Chaharbagh in Safavid Isfahan. Beginning in the 1880s, some tile panels had already been removed from the Jahan-nama and were acquired by art dealers and collectors. The pavilion was ordered to be demolished between 1896 and 1897 at the request of rulers of Iran at the time. At some point soon thereafter, these 10 tiles were probably acquired by collector Hagop Kevorkian from dealers in Iran. They were part of a sale of Kevorkian’s collection in 1927 at Anderson Galleries in New York, before Iran established an export ban in 1930. They next appeared on the art market in a 1973 Sotheby’s sale in New York City, when Timken purchased them.

In researching this acquisition candidate, SCMA curators Danielle Carrabino and Yao Wu consulted several experts on Islamic art and architecture. Among them, Professor Farshid Emami of Rice University helped to identify the precise locations of all 10 tiles that once adorned an exterior arch at the Jahan-nama pavilion, based on 19th-century historical photographs. His upcoming book Isfahan: Architecture and Urban Experience in Early Modern Iran will feature the SCMA tile panel. After these tiles were accessioned into the SCMA collection, they were sent to the Williamstown Art Conservation Center for treatment. Object conservator Hélène Gillette-Woodard discovered areas of heavy and extensive overpainting on the original surface. With SCMA’s plans to exhibit them in the near future, the tiles will continue to accumulate more attention and interest in their new home.

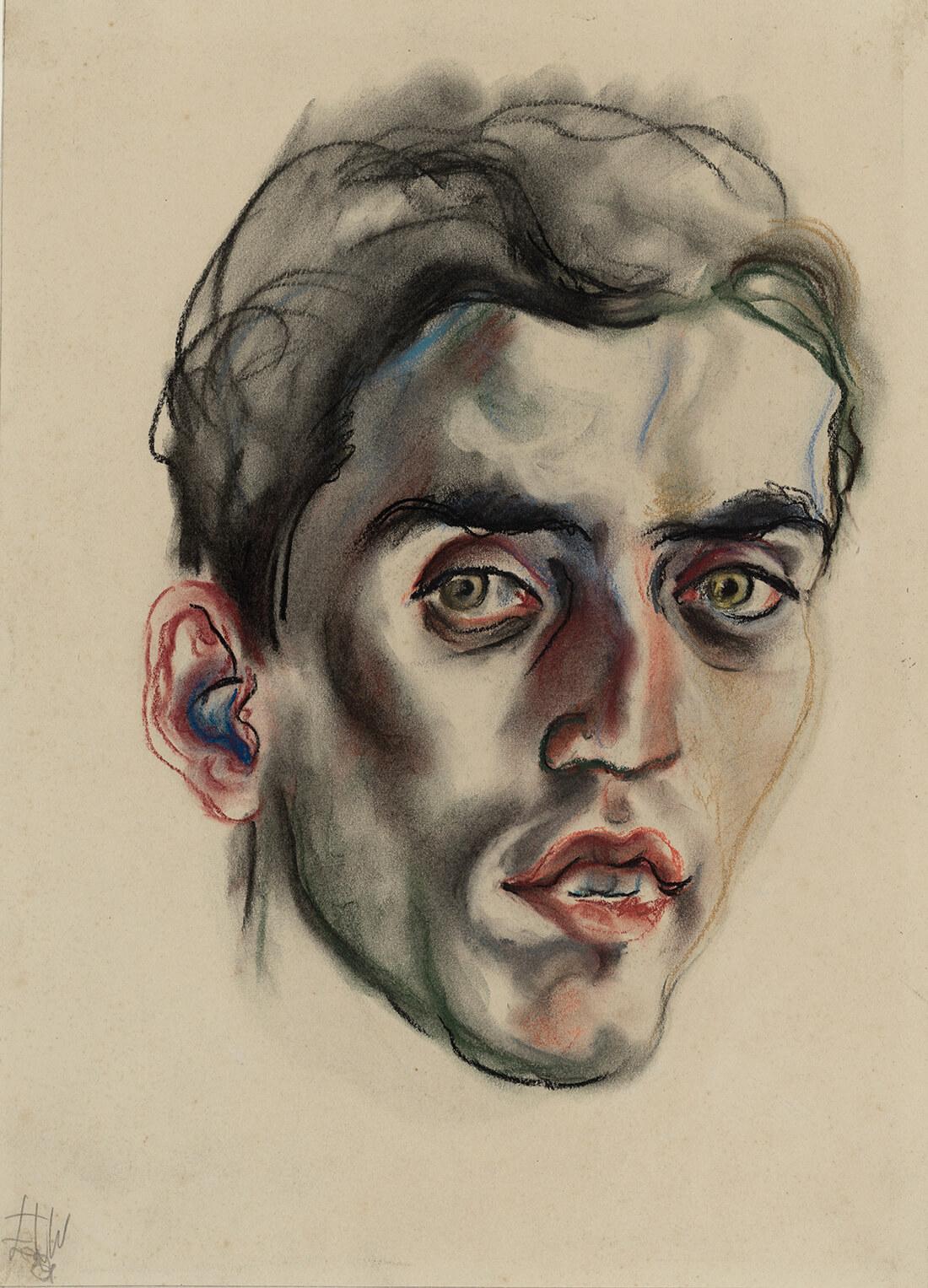

elfriede lohse wachtler

Elfriede Lohse Wachtler. German, 1899–1940

Portrait of Wölbers, 1929

Charcoal and pastel on thick,

slightly textured cream-colored paper

16 3/8 x 11 3/4

Purchased with the Katharine S. Pearce, class of 1915,

Fund, the Margaret Walker Purinton Fund and the

gift of the Almathea Foundation

SC 2021.16.2

The SCMA collection is rich in German 20th-century drawings, but few of these works are by women. This compelling portrait by the underrecognized Dresden artist Elfriede Lohse Wachtler was thus an important addition, as diversifying the SCMA collection is a priority.

Wachtler studied at the Royal Arts School from 1915 to 1919 and continued at the Dresden Art Academy. She was associated with radical art circles such as Spartakus bund and the Dresden German Expressionist Secession group. Her circle included artists such as Otto Dix, Otto Griebel and Conrad Felixmüller. Wachtler sometimes exhibited as “Nikolaus,” signing works with initials rather than her full name. She also cropped her hair and adopted masculine clothing.

Wachtler suffered a nervous breakdown in 1929 and was committed to a psychiatric care facility in Hamburg–Friedrichsberg. While there she remained artistically productive, creating portraits of fellow patients, such as Portrait of Wölbers.

In the portrait, Wachtler uses strong lines and only a few colors. As in her earlier portraits of sex workers and people experiencing homelessness, Wachtler does not convey the cynicism or disdain for her subjects often seen in the work of her contemporaries. Here Wölbers’ dark eyes are soulful and tragic. The kinship found in this portrait of one of her fellow patients demonstrates the artist’s deeply felt connection to her subjects.

Wachtler was the victim of the National Socialist government’s forced sterilization program in 1935, after which she stopped creating art. The artist was killed in 1940 as part of the Nazi program of exterminating those with physical or mental disabilities. It may have taken many decades, but art historians are finally recognizing artists like Wachtler who have been historically marginalized.

richmond barthé

Richmond Barthé. American, 1901–1989

The Negro Looks Ahead, 1944; cast ca. 1979

15 5/8 x 10 3/4 x 11 1/4 inches

Purchased with the Kathleen Compton Sherrerd,

class of 1954, Acquisition Fund for American Art,

and the Museum Acquisitions Fund

SC 2022.14

The bronze sculpture The Negro Looks Ahead by Harlem Renaissance artist Richmond Barthé (1901–89) is the earliest sculpture by an African American artist to enter the SCMA collection. Barthé’s art celebrates Black bodies as beautiful and strong. This work encapsulates the African American spirit from the perspective of an African American artist. In addition to adding a new artist that has been historically marginalized, the sculpture resonates with many of the works already present in the collection.

James Richmond Barthé was born in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, to Creole parents. Living in the segregated south, Barthé was denied the opportunity to study art formally. He was admitted to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago without a high school education. Upon graduation, Barthé moved to New York City at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. Barthé enjoyed success there in the 1930s and ’40s, becoming one of the best-known contemporary African American artists.

In 1944 he created The Negro Looks Ahead for an exhibition in support of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s third candidacy for president. According to the artist, “the Negro advanced more under [Roosevelt] than any other President since Lincoln, so I did this piece of the Negro emerging out of his rough background with hope in the future.” Imbued with the spirit of the time, this iconic work of art later graced the cover of Cedric Dover’s groundbreaking book American Negro Art (1960), one of the earliest illustrated surveys of African American art.

Barthé ordered several casts of The Negro Looks Ahead over the course of his life. After he left New York City to live abroad, these casts brought in income at a time when he was suffering from health problems and unable to work. The SCMA bronze was cast in 1979 by the Modern Art Foundry in New York. It was commissioned by the Johnson Publishing Company, a Black-owned business in Chicago that produced Ebony and Jet magazines. It remained in the Johnson collection until 2020, when it was sold at auction and purchased by a dealer, who sold it to SCMA two years later.

The Negro Looks Ahead presents an image of ideal beauty that transcends gender, time and place. It joins SCMA's distinguished collection of American, European and African bronzes from antiquity to today. It also relates to other works in the collection created around the same time, such as John Wilson, My Brother (SC 1943.4.1) as well as more recent works by Isaac Julien and Amanda Williams. Barthé’s sculpture will be essential for teaching and will help lay the foundation for future acquisitions of African American art.

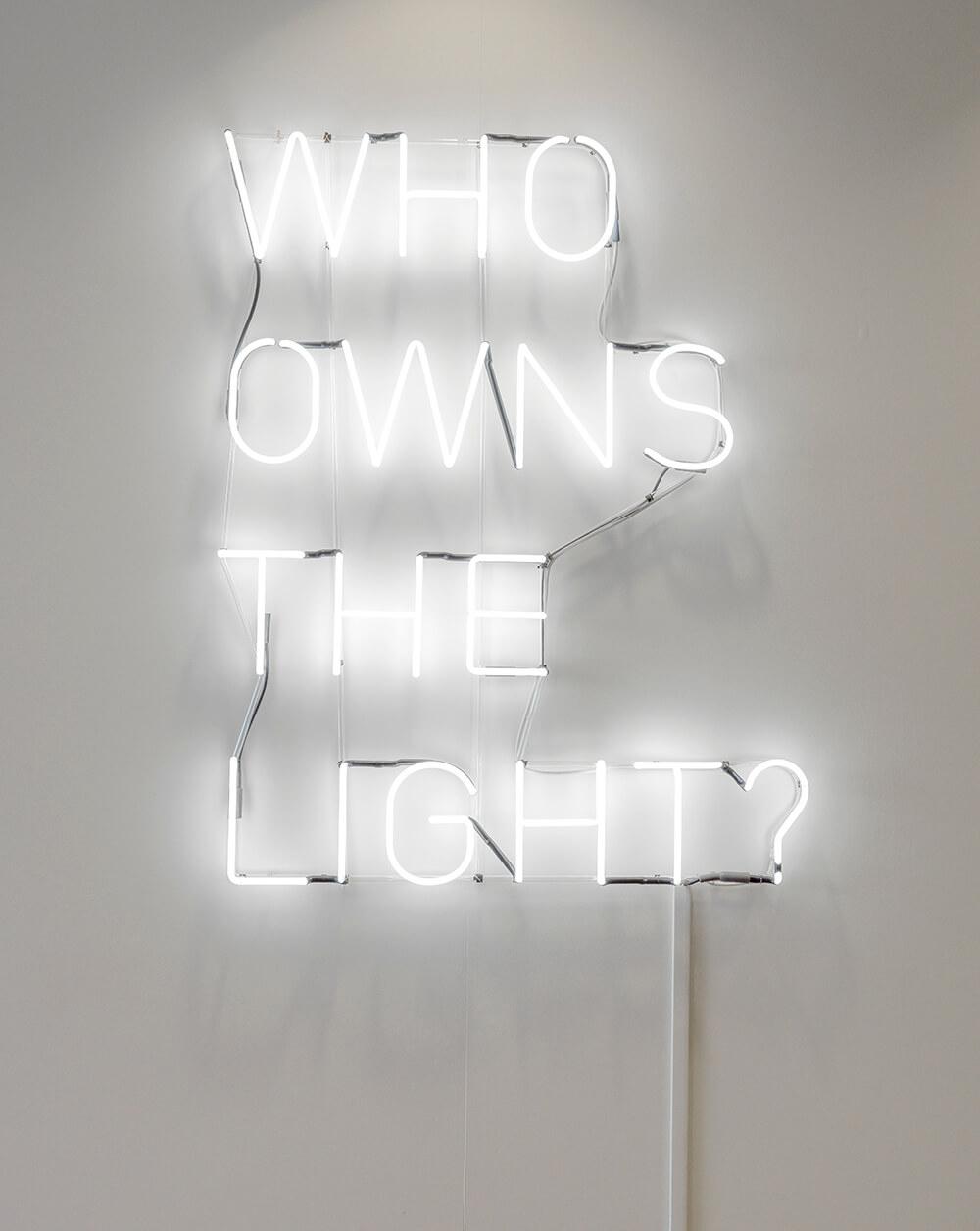

hương ngô

Hương Ngô (American, born 1979)

Who Owns The Light? 2017, neon fabricated 2021

White neon

Purchased with the Kathleen Compton Sherrard,

class of 1954, Acquisiton fund for American Art

In September 2022, preparators Nik Asikis and Matthew Cummings installed Who Owns The Light?, a neon sculpture by the artist Hương Ngô, in SCMA’s lobby. It is the first artwork that visitors and staff encounter when entering SCMA and the last work they see before departing. Previously, one had to pass through four sets of doors before seeing any art. Now the sculpture is visible before (or even without) entering the building. This acquisition emerged both from SCMA’s multi-year-long relationship with Ngô and from the 2020 exhibition Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem. During that exhibition, the museum installed a different neon sculpture—Glenn Ligon’s Give Us a Poem (2007)—in the lobby, a location selected to evoke the artwork’s iconic location inside the entrance to the Studio Museum.

Ngô’s interdisciplinary and research-based practice engages archives, feminist histories and the places where the personal and the political meet. She was born in 1979 in Hong Kong, where her family took refuge after the Vietnam War before emigrating to the United States. Ngô received the prestigious Chicago 3Arts Award in 2018. She attended the Whitney Independent Study Program (2012) and is a former Fulbright Scholar (2016) and fellow at the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France (2018). In 2017, SCMA became one of the first public art institutions to acquire her work when it purchased the video The Voice is an Archive (2016).

Ngô originally created Who Owns The Light? for her 2017 solo exhibition, To Name It Is To See It, at the DePaul Art Museum (Chicago, IL), which focused on the relationship between language and sight. In writing for the exhibition’s accompanying publication, art historian Faye Gleisser argued that Who Owns The Light? functioned as the exhibition’s lynchpin: “The symbolism of light . . . underscores the politics of the Enlightenment, the European intellectual movement that emphasized reason and individualism and was used to justify colonial conquest.” At DePaul, the sculpture was installed in a gallery window facing the Fullerton CTA stop, where it was visible to riders.

Who Owns The Light? effectively frames one’s time in the museum with a query whose grammatical simplicity belies its complexity. For Ngô, contained within the question of “who owns the light?” are questions about “who claims the authority over the production of knowledge?” and “who is allowed to benefit from that knowledge?” At the same time, because the word “light” could refer to the lit neon itself, the artwork refers to its own materiality, inviting conversations about conceptual art, language, capitalism and commodification. As an art museum on a college campus—two modern institutions that are, in many ways, the product of Enlightenment thought—SCMA is an ideal site to foreground these questions of how and whose knowledge is produced and circulated, valued and claimed.