student voices

Student Voices: Kayara Hardnett-Barnes ’23

Originally published as “What Does It Mean to Be American?” October 13, 2021, SCMA blog (https://scma.smith.edu/blog/what-does-it-mean-be-american), this piece has been lightly edited for publication in SCHEMA.

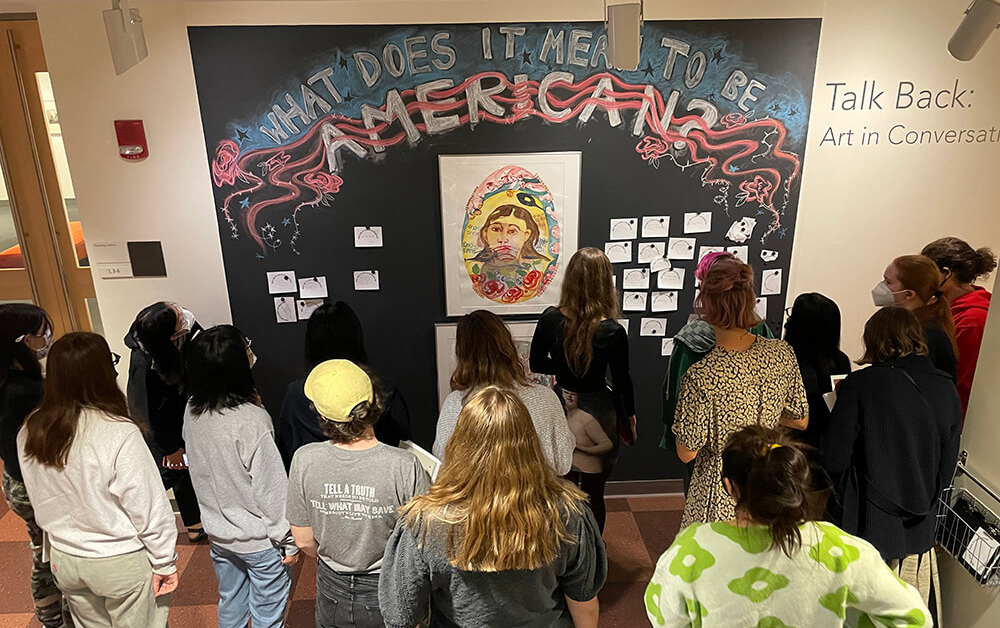

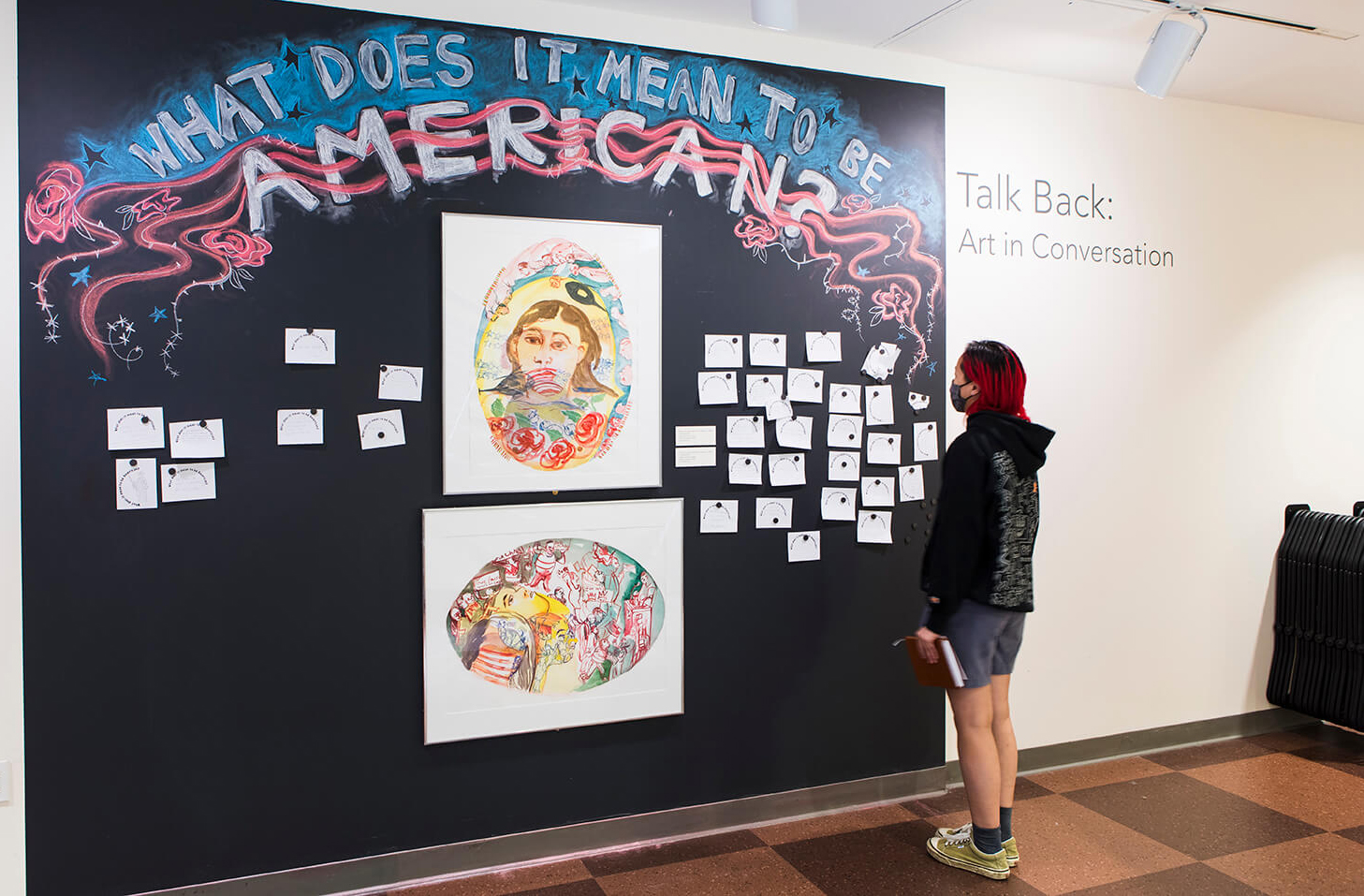

During the summer of 2021 I worked with Gina Hall, SCMA’s educator for school and family programs, on selecting an artwork for SCMA’s Talk Back space. The space is an area where an artwork is hung on a wall alongside a question written in chalk. Slips of paper, pencils and magnets are available for viewers to leave their responses to the question around the work of art. Since the theme of the current school year is democracies, we went into the process of selecting a work of art with that in mind in the hope that it would provide additional encouragement for students to respond.

We began our search by looking through the database of SCMA’s collection, focusing on works on paper. We wanted to find a work that was fairly large, had a lot of details to be discussed and that was clear. Considering that the museum has more than 24,000 works on paper, we had a lot of choices. That said, we could only use the works that have been fully catalogued and matted. When Gina and I first met with curator Aprile Gallant, for example, we asked to see some works from English artist Sue Coe. A few of the works by her we were hoping to see were unfortunately not matted. As we walked into the Cunningham Center, however, we noticed another artwork that was on display in preparation for a visit by Smith College’s Precollege Programs. The work was the first of two watercolor works by Maria De Los Angeles, both called Untitled. Gina and I were immediately captivated.

Now that we had selected artworks, the next step in the process was to begin thinking of a question to accompany the art. Gina and I started by printing out images of the watercolors and hanging them in the Talk Back space, then practicing “slow looking” to see what we noticed. We took some time to observe in silence. As we began noticing different things, we pointed them out to each other and then resumed looking. After that I took some time on my own to do some background research on the artist. I found out that Maria De Los Angeles is a DREAMER from Mexico who grew up in California. I watched some interviews and informational videos about her and learned that she often explores themes of home, displacement and love, among other similar concepts. After I had finished researching, I thought further about what I had found in combination with my initial takeaways. I wrote down the first words that came to mind:

Flags

Patriotism

Immigration

Xenophobia

Sense of homeborder

War

Government

Law

Agriculture

California

Jobs

Rallies

Protests

Vulnerability

Protection

Anger

Silencing

Identity

Freedom

I took those concepts and created about six different questions, all in rough draft form. The next step was to edit, edit, edit. Then, Gina pulled out a small easel and put a blank piece of paper on it. We wrote out our favorite questions and talked about what we liked and disliked about the choice and placement of different words. We placed ourselves in the shoes of visitors and thought about the significance of the questions in relation to the artworks.

For example, here are two of the initial drafted questions.

What does American patriotism look like to you?

I was inspired to write this question based on a powerful depiction in one of the artworks of a figure whose mouth is being covered by an American flag, and also based on some of De Los Angeles’ interviews. While I originally liked this question the best, discussions with Gina revealed to me how divisive and aggressive the word “patriotism” has become, especially in the United States. Looking at De Los Angeles’ works with that phrase in mind does creates a powerful story, but it also leads the viewer into a particular interpretation. While we want to write questions that honor the artist’s intentions, we also want to give viewers room to notice other aspects of the work and come to their own conclusions about what it is ultimately saying. If a viewer does think of patriotism, I want to give them the space to do so on their own and let the work speak for itself.

Have you ever felt silenced in your life? If so, in what ways?

I wrote this question with the goal of having any viewer relate to it and to be able to comfortably answer. The problem with this approach, I realized, is that it gives too much room for some of the important themes of both artworks (identity, nationalism, race, gender, etc.) to be lost. A question like this one takes away the specificity of who is being silenced in the artwork, thus silencing them even further for the benefit of comforting the viewer.

As Gina and I continued to discuss these questions and the many others, I asked myself: How does this question make me feel? How does it enhance the experience of observing this work of art? Our goal is to write questions that encourage museum visitors to think deeper about a work of art. The questions should not only promote closer looking but also touch upon the intentions of the artist. In the end, we settled on this question:

What does it mean to be American?

This question does a lot of work in a small amount of words. It asks those who are American to look within and around them and comment on what they see and feel. It asks those who are not American to shed light on what values and intentions they observe from the outside. It introduces the topic of citizenship in a subtle yet bold way and encourages us to think about the discourse surrounding the process of becoming and remaining a permanent resident of the United States safely. It holds space for talking about privilege and who is allowed to feel as though they belong. Most importantly, however, it asks us to dissect and deconstruct the meaning and history of being “American” and to consider who reaps the benefits of such a title.

My favorite part of the process of constructing the Talk Back space was workshopping and thinking deeply about what questions to ask. The final step was to install the artwork and design the question in chalk above it, which was beautifully done by Sophie Willard Van Sistine ’22J. Sophie used the iconography from the watercolors to inform her design. I love walking down to the lower level and seeing her wonderful work completed by all the powerful responses being left on the wall every day.

Student Voices: Brooklyn Quallen ’25

When I applied to Smith, I knew exactly what I wanted to study. I would major in government, probably do a second major in history and have absolutely no time to explore anything else. Museums weren’t even a blip on my radar. That was my plan, right up until I got a STRIDE (Student Research in Departments) scholarship. The scholarship meant that, suddenly, I had a little bit of wiggle room in my color-coded five-year plan to take on a two-year research project. I just had to choose which one! There were projects that fit nicely with my prospective majors, but I knew that I also had the chance to use this opportunity to step out of my comfort zone and explore something completely new. That’s how I ended up as curator Emma Chubb’s STRIDE student.

Two years in, I’ve tried a number of new and different things. I’ve written object labels and blog posts, captioned videos and learned to love filing. My favorite thing so far, though, has been object file research. Archival research was not something I’d done much of before coming to Smith. It wasn’t the kind of research that I was used to; instead of a quick search popping up a thousand papers to read on a concept, I found myself in the basement of Hillyer Art Library trawling through journals from the 1960s for reviews of different pieces and shows. I checked out 1950s exhibition catalogues from Neilson Library instead of textbooks. I read Grace Hartigan’s diaries, transcripts of interviews with Mary Bauermeister and Betye Saar’s personal notes. I followed various threads wherever they led, even though they sometimes led absolutely nowhere. As new and sometimes frustrating a task as this research was, I quickly found myself enjoying it. I loved hunting down these stories and putting the puzzle pieces together. It has been the backbone of most of my other tasks at the museum, including my current work preparing for the 2023 Artist in Residence, Abdessamad El Montassir.

Working as Emma’s STRIDE student has been an invaluable experience for me, even though I don’t plan on working in museums after Smith. It has encouraged me to be curious both in and out of the museum, and it has given me the tools I need to find the answers to my questions. The work I’ve done and the skills I’ve gained will follow me well beyond the Records Room. I’m incredibly grateful for the time I’ve spent here and I’m excited to see what this spring will bring. The rest of my time at Smith probably won’t take place in SCMA, but I have a feeling I’ll gravitate back here.

Kayara Hardnett-Barnes ’23 top: Students in Barbara Kellum’s museum-based first-year seminar—FYS 197: On Display: Museums, Collections and Exhibitions—consider Maria De Los Angeles’s work in the Talk Back space. Photo by Charlene Shang Miller; middle: Photo courtesy of Kayara Hardnett-Barnes ’23; bottom: A student engaging in the Talk Back space, themed “What Does It Mean to be American?” Photo by Lynne Graves for SCMA

Brooklyn Quallen ’25 bottom right: Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Quallen ’25